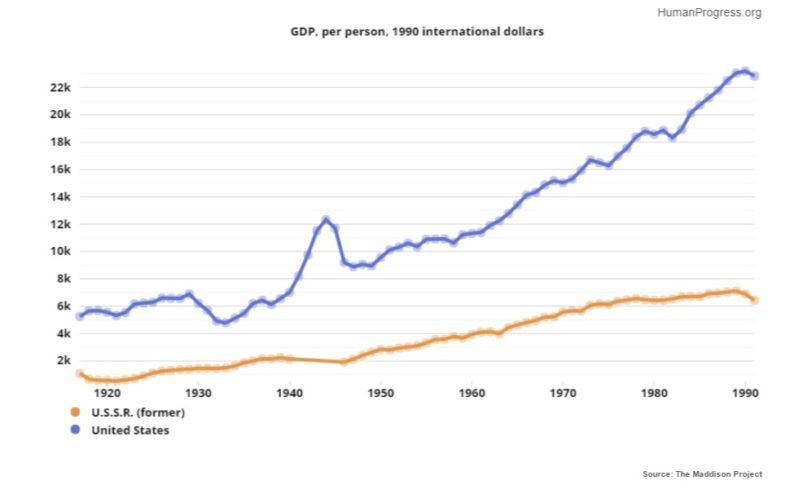

Albert Einstein is supposed to have defined insanity as “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.” Yet, as the economic implosion of Venezuela reminds us, we seem to be unable to stop repeating the same terrible mistake: trying to make socialism work.

To explain our insane fascination with socialism, I have pointed to a growing body of academic research, which suggests that we are, by nature, envious of and resentful toward people who amass “disproportionate” wealth and power.

Moreover, research suggests that we find it difficult to comprehend, let alone appreciate, what Friedrich Hayek called extended order – or the use of specialization and trade to create “an information gathering process, able to call up, and put to use, widely dispersed information that no central planning agency, let alone any individual, could know as a whole, possess or control”.

Our minds have evolved to deal with issues faced by our hunting and gathering ancestors (e.g., an exchange of meat for sex) not to deal with issues facing us today (e.g., outsourcing the assembly of the iPhone to China to make it more affordable in America). The extended order, in other words, has evolved in spite of, not because of, our best efforts.

Today, I want to address another reason behind the persistent appeal of socialism: the power of self-delusion, or our ability and willingness to go on believing in things that are patently not true.

Consider the following two examples. In 1985, my Czechoslovak aunt Kate visited the USSR. She was a committed Communist Party member all of her adult life and, as a reward, she was given a chance to spend a couple of weeks in the workers’ paradise. When she returned, I impetuously asked her if she had brought me anything. “Nothing,” she replied much to my disappointment, “the USSR is a very poor country”. Yet Kate never wavered in her commitment to the principles of communism and remained a party member until 1989, when her entire value system came crumbling down along with the Berlin Wall.

Some ten years later, an American college professor of mine recalled his own visit to the USSR. In 1970, he and his wife spent two weeks in Leningrad, Moscow and Kiev. During their stay in the communist country, he was shocked by the poverty and inefficiency he saw. (From Kiev, he wrote a letter to his parents in New York, which I have transcribed, with his permission, below.) All the other tourists that he met expressed similar sentiments.

When he returned to the United States, however, he kept on reading reports in mainstream publications, including Time magazine and The New York Times, which maintained that the Soviet economy was working. These reports were written by people who lived in the USSR, spoke Russian and had Soviet friends. As such, he concluded that the impressions he had made during his stay in the USSR were not valid.

If the above two examples failed to convince you of the power of self-delusion, consider our Nobel Prize-winning physicist from Ulm.

Einstein was a self-declared socialist. In 1949, he even published an essay titled, Why Socialism? In it, Einstein wrote, “The economic anarchy of capitalist society as it exists today is, in my opinion, the real source of the evil [of human suffering]… I am convinced there is only one way to eliminate… [this evil], namely through the establishment of a socialist economy.”

It is striking that the most brilliant scientist of the 20th century, who escaped from national socialist Germany (Hitler called his party “socialist” for a reason) and moved to the capitalist United States, published an essay castigating capitalism and calling for socialism – while Stalin was still alive and busy butchering millions of Soviet citizens.

Smart enough to come up with the theory of relativity and observe that “gravitational attraction between masses results from the warping of space and time,” Einstein could not comprehend the benefits of “anarchic” production under capitalism (“You don’t necessarily need a choice of 23 underarm spray deodorants or of 18 different pairs of sneakers,” as Bernie Sanders would put it 66 years later), preferring socialism instead.

It is equally striking that Einstein wrote “Why Socialism?” while living in Princeton in the late 1940s and the early 1950s. As such, he would have enjoyed historically unprecedented levels of luxury and abundance. Yet, Einstein bemoaned the economic system that made that prosperity possible and longed for its opposite.

Our brains might be predisposed to be suspicious of capitalism, but we should not ignore the role played by self-delusion in paving the way for a future return of socialism.

Hotel Dnipro, Kiev

Dear Parents,

We are on the train leaving the USSR. It’s a funny thing. In the last few years I’ve been becoming more liberal [Editorial note: i.e. left-wing]. I’d come to accept communism as just another system. But my stay in Russia has put me back in the ultra-conservative camp. Not the most raving right winger has ever adequately described how horrible this country is.

Where can I begin? Maybe the food. $1.80 for a mooshy orange. $1 for 3 tomatoes with fungi growing on them. Walnuts the likes of which you never saw (I still don’t understand how you can ruin a nut) – and don’t forget when you look at these prices that a medical doctor earns $1,200 a year. The meat and fish are utterly uneatable.

After a little while we got used to eating what the Russians subsist on – bread. This is the only food which is eatable and cheap. The effect of this diet is very obvious. The Russians are all fat and bloated. Even little children have fat bellies and double chins (this in a country where 40% of the population is farmers). Incidentally the wheat for the bread is imported from Canada.

When you walk the streets and they see you’re a tourist (this they can tell immediately by the cut of your clothes, shoes or the possession of one of the innumerable luxuries which distinguish the tourist –a watch, camera, etc.) they besiege you clamoring for chewing-gum, ball point pens, etc.

The new houses that they are putting up are already cracking and splitting before they are finished. We met a British ships engineer who is married to a Russian girl who is a doctor (she’s moving to London in a few months). In the apartment in which she lives, 9 families share 1 toilet with no facilities for bathing or showering. We asked him how they washed and said they didn’t – they smell.

Not only are refrigerators unknown but also ice-boxes are unknown. They have no means of food storage at all and drink their milk sour. Huge lines are everywhere and everyone one encounters is unbelievably lackadaisical and inefficient.

But the most horrible thing is the people’s faces – 13 days without seeing a smile, only hard, bitter, scowling faces with eyes that peer out suspiciously. Couples walking arm and arm down the street scowling. People playing checkers in the park scowling, little children scowling.

And don’t forget what we saw were only the biggest cities. The communists showcase – they themselves admit that they have “starved the country for the city”. We met tourists who went through the countryside and what they saw was fantastic – cities without electricity or plumbing. Farmers using wooden plows and horses. Families living in hovels or, if they’re lucky, deserted railway cars.

As far as class-consciousness and rigid class lines the likes of which I didn’t think existed anywhere any more, will not attempt to describe in a letter.

What kept occurring to me was that this is it. The communists have been in control of Russia for over half a century. The people have gone through immeasurable blood, sweat and tears – for this. One of the communists favorite slogans is “the ends justify the means”. The means were mass murders, huge forced labor camps and constant terror. The ends are what we saw.

Steven