On Monday, William Nordhaus and Paul Romer were awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics. Nordhaus, the Sterling Professor of Economics at Yale University, is best known for his work in economic modelling and climate change. Romer, who teaches at New York University, is a pioneer of endogenous growth theory, which holds that investment in human capital, innovation, and knowledge are significant contributors to economic growth.

The two American economists’ research is vital in showing the way people underestimate the progress humanity has already made and the likelihood that it will continue well into the future.

In his 1996 paper, Do Real-Output and Real-Wage Measures Capture Reality? The History of Lighting Suggests Not, Nordhaus looked at the economics of light. Open fire, he noted, produced a mere 0.00235 lumens per watt (a lumen is a measure of how much visible light is emitted by a source.) Lumens per watt refers to the energy efficiency of lighting. A traditional 60 watt incandescent bulb, for example, produces 860 lumens.

A sesame lamp could produce 0.0597 lumens per watt; a sperm tallow candle 0.1009 lumens; whale oil 0.1346 lumens and an early town gaslamp 0.2464 lumens. An electric filament lamp, which was launched in 1883, achieved an unbelievable 2.6 lumens per watt and, due to subsequent technological improvements, managed to deliver an astonishing 14.1667 lumens by 1990. Yet that’s small beer compared to the compact fluorescent lightbulb, which delivered 68.2778 lumens per watt when it was launched in 1992.

William Nordhaus

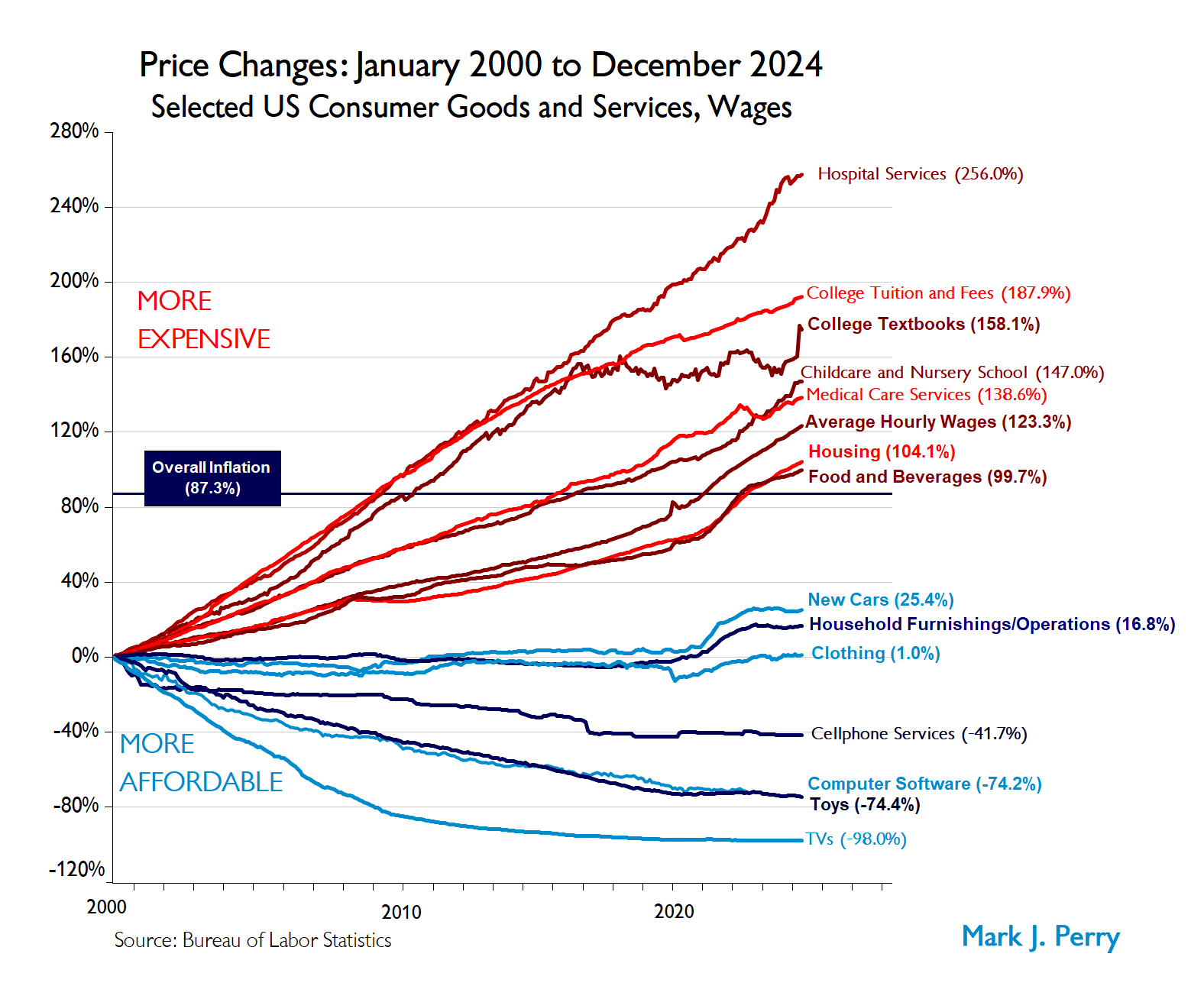

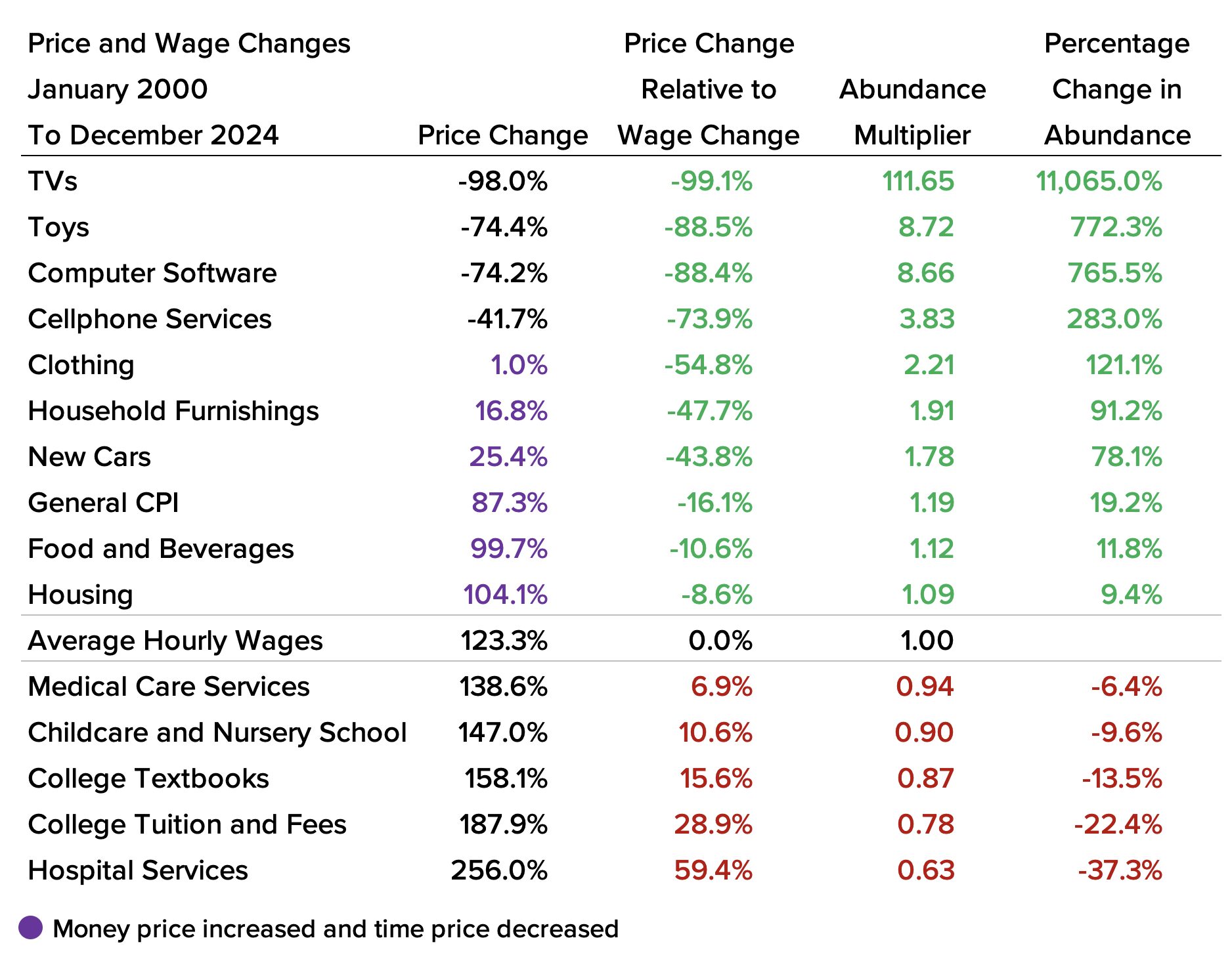

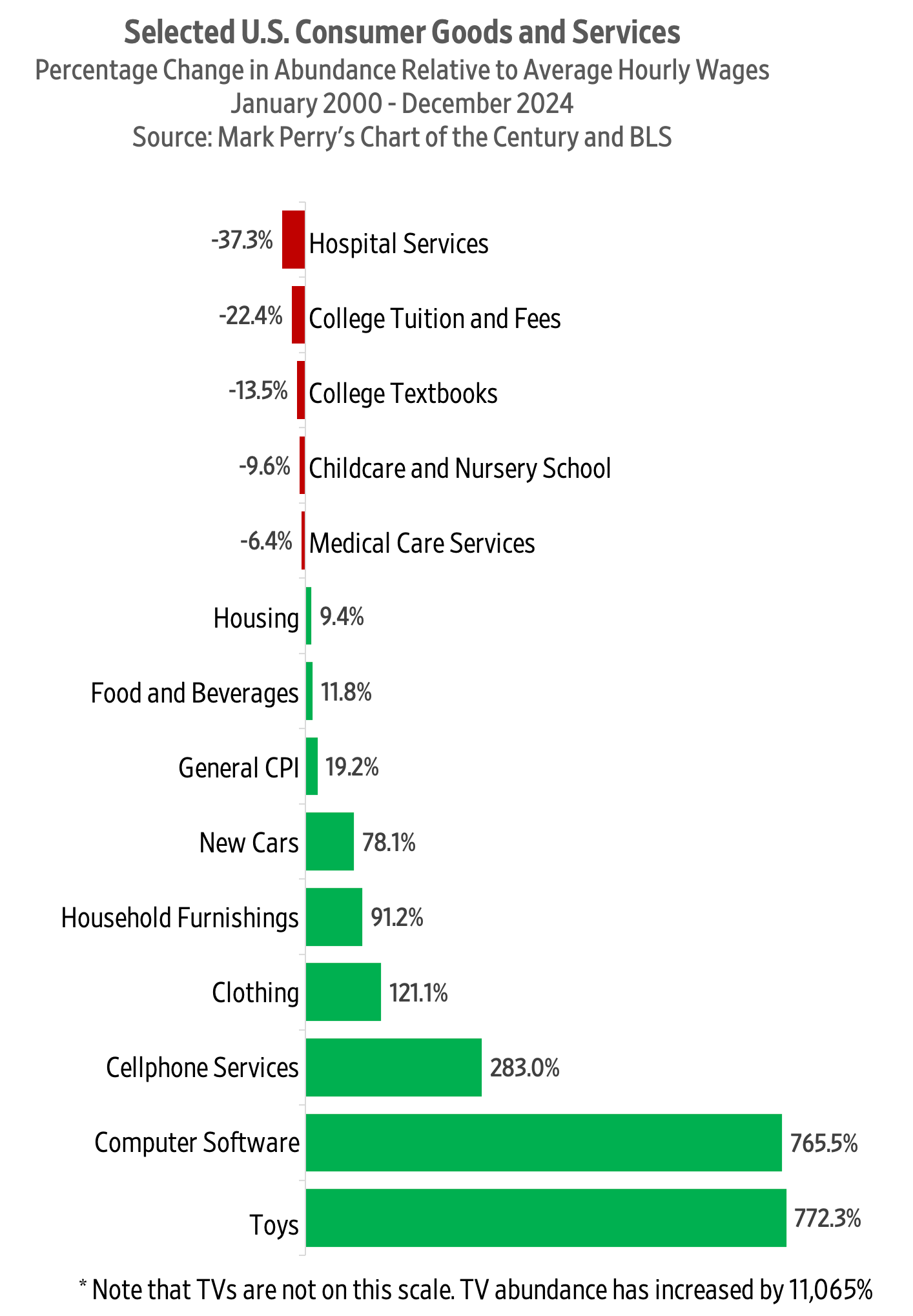

Accompanying these amazing improvements in the efficiency of lighting was a collapse in its price, both in absolute terms and in terms of human labour. Nordhaus estimates that the price of light per 1,000 lumens was $785 in 1800. By 1992 that price had dropped to 23 cents (both figures are in 2018 dollars). That amounts to a reduction of 99.97 percent. Today, the monetary cost of lighting per 1,000 lumens is inconsequential.

Now, consider the price of lighting from the perspective of human labour. Prior to the Neolithic revolution, which put an end to our nomadic past and turned our species into agriculturalists, it took more than 50 hours of labor (mostly gathering wood) to “buy” 1,000 lumen hours of light. By 1800, it took about 5.4 hours.

By 1900, it took 0.22 hours. By 1992, 1,000 lumen hours required 0.00012 hours of human labor. That amounts to a reduction of close to 100 per cent. As Tyler Cowen of George Mason University noted, Nordhaus found that “GDP figures understate the true extent of growth, and show[ed] that the relative price of bringing light to humans has fallen more rapidly than GDP growth figures alone might indicate.”

Put differently, technological change, which is not fully captured in GDP figures, makes us underappreciate the tremendous advance in standards of living over that of our ancestors. Can that advance be sustained and, even, improved upon? That’s where Romer enters the picture.

Many people worry that rising standards of living are unsustainable. Economic growth, they fear, will lead to exhaustion of natural resources and civilisational collapse. Just last year, Stanford University biology professor Paul R. Ehrlich noted that “You can’t go on growing forever on a finite planet. The biggest problem we face is the continued expansion of the human enterprise … Perpetual growth is the creed of a cancer cell.”

The earth, it is true, is a closed system. One day, we might be able to replenish our resources from outer space by, for example, dragging a mineral-rich asteroid down to Earth. In the meantime, we have to make do with the resources we have. But, what exactly do we have?

Paul Romer

According to Romer, we do not know the full extent of our resources. That’s because what matters is not the total number of atoms on Earth, but the infinite number of ways in which those atoms can be combined and recombined. As he put it in his 2015 article “Economic Growth”:

Every generation has perceived the limits to growth that finite resources and undesirable side effects would pose if no new recipes or ideas were discovered. And every generation has underestimated the potential for finding new recipes and ideas. We consistently fail to grasp how many ideas remain to be discovered.

The difficulty is the same one we have with compounding. Possibilities do not add up. They multiply.… To get some sense of how much scope there is for more such discoveries, we can calculate as follows. The periodic table contains about a hundred different types of atoms. If a recipe is simply an indication of whether an element is included or not, there will be 100 x 99 recipes like the one for bronze or steel that involve only two elements. For recipes that can have four elements, there are 100 x 99 x 98 x 97 recipes, which is more 94 million. With up to five elements, more than 9 billion. Mathematicians call this increase in the number of combinations ‘combinatorial explosion.

Once you get to 10 elements, there are more recipes than seconds since the big bang created the universe. As you keep going, it becomes obvious that there have been too few people on earth and too little time since we showed up, for us to have tried more than a minuscule fraction of the all the possibilities.

Figuring out the availability of resources, therefore, is not about measuring the quantity of resources, as engineers do. It is about looking at the prices of resources, as economists do. In a competitive economy, humanity’s knowledge about the value of something tends to be reflected in its price. As new knowledge emerges, prices change accordingly.

Nordhaus showed that the price of light collapsed as a result of innovation. Romer showed that human potential for innovation is infinite. The two men are apostles of human progress and well deserving of the highest accolade that the discipline of economics can bestow.