Summary: Vaping can help America quit smoking, a habit that causes millions of deaths and diseases each year. This article presents evidence that vaping improves public health and criticizes the regulations that hinder vaping’s life-saving potential.

Last month, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration authorized the sale of the Vuse Solo, a first-of-its-kind acknowledgment that ENDS (electronic nicotine delivery system) products have a positive impact on public health.

According to the FDA’s Technical Project Lead Review, “studies have shown that daily ENDS use is associated with significant reductions in combusted cigarette use.” The review also suggests that devices like the Vuse Solo are much less toxic than cigarettes, greatly reduce smokers’ exposure to carcinogens, and appeal mainly to cigarette-using individuals.

In short, more vaping means less cigarette smoking, and that’s a good thing for public health. According to one study, if every U.S. smoker switched to e-cigarettes, it would prevent between 1.6 and 6.6 million premature deaths, depending on the long-term risks of e-cigarette use and the number of non-smokers who begin vaping.

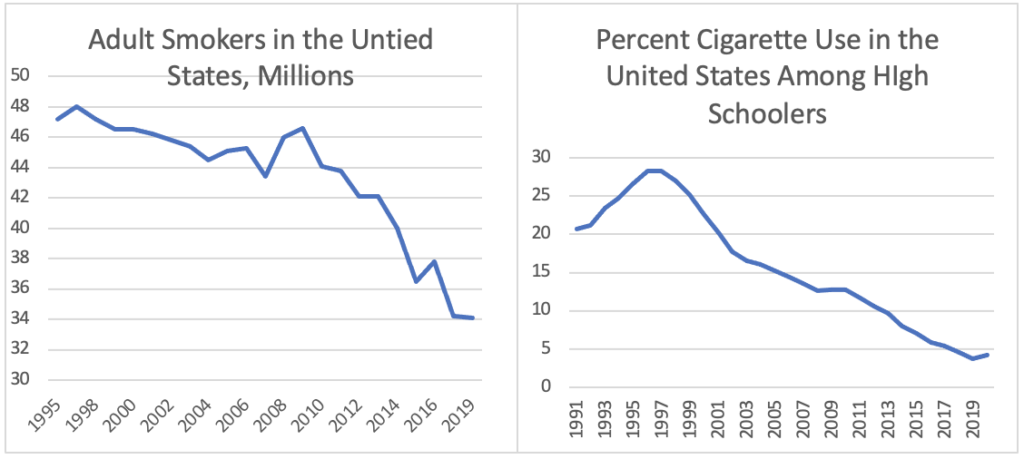

Thankfully, smoking is in decline. In 2019, the CDC reported 13.1 million fewer adult smokers than in 1995. Additionally, data suggests that cigarette use has also plummeted among high schoolers. According to a survey from the University of Michigan, the rate at which teens are smoking has been cut by two-thirds over the last decade. The study found only 4.2% of respondents used cigarettes in 2020, down from 12.8% ten years prior.

With the new FDA acknowledgment, the vaping industry may finally be able to take some credit for this reduction.

Unfortunately, FDA regulations still undermine the vaping industry. The process by which companies must seek FDA authorization is prohibitive to innovation and hazardous to health. Up until a vape product receives premarket authorization from the FDA, it cannot be bought or sold in the U.S. Applications for authorization closed last year, and the grace period for removing vapes from shelves ended in September. In other words, the vaping industry is in legal limbo until the FDA concludes its review of premarket applications.

These regulations limit current sales and reduce the vaping industry’s long-run desire to innovate. Each new vape product brought to market must submit its own premarket authorization application. This means even minor improvements to a device will cost vape companies a significant amount of time and money, disincentivizing innovation.

While the FDA authorized the Vuse Solo in the Tobacco flavor, the agency rejected premarket authorization for several other products in the Vuse family on the grounds that their e-liquid varieties may attract teenagers. Regulatory scrutiny of flavored tobacco products started back in 2018 when the Surgeon General issued an advisory against “kid friendly flavors,” and the Trump administration banned the sale of all closed-system e-liquid pods, except for tobacco flavored products.

Since then, as the CDC’s most recent National Youth Tobacco Survey suggests, electronic cigarette use among teens has decreased to 11.3%, whereas just two years prior, the percent-use among teens was 27.5%.

Tighter flavor controls, however, may not be causing this drop in teen vaping. Although companies no longer produce closed-system pods in non-tobacco flavors (the type prohibited under regulations from the Trump administration), selling disposable vapes and refillable e-liquid products is still permitted in non-tobacco varieties. According to the CDC survey, disposable vapes were the most attractive for high schoolers in 2021, meaning teens accessed flavored products even when the government tried to prohibit them.

So, if the government isn’t stopping youth vaping, who is? One explanation may be that the initial cohort of teens toying with vapes is no longer teenaged. The National Youth Tobacco Survey only looks at high school-aged individuals. The group that would have taken the survey during the spike in 2018 is now in college and no longer qualifies. Additionally, information about the harms of adolescent nicotine exposure has been widely circulated through a targeted campaign of online public service announcements from various interest groups, which likely contributed to the overall decrease in teen vaping.

Extensively regulating ENDS products isn’t conducive to improvement in U.S. smoking rates. In fact, by inefficiently regulating the vaping market, the government is impeding America’s opportunity to quit its smoking habit.