Summary: Thomas Malthus predicted in 1798 that population growth would outstrip food production and lead to collapse. However, he did not check his model against reality. Using data from England, this article shows that food abundance actually grew faster than the population during the 18th century.

A version of this article originally appeared in Gale Pooley’s Gale Winds Substack.

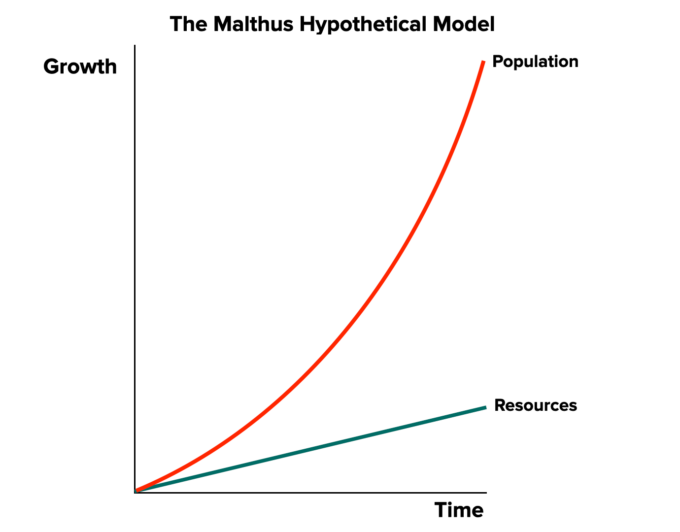

Using an untested hypothetical model, Thomas Malthus told the world in his 1798 An Essay on the Principle of Population to expect collapse. He cloaked his model in mathematics instead of empirical evidence. He noted, “Population, when unchecked, increases in a geometrical ratio. Subsistence increases only in an arithmetical ratio.” See Figure 1. To ensure that he had the illusion of math on his side, he condescendingly added, “A slight acquaintance with numbers will show the immensity of the first power in comparison of the second.” If Malthus had checked the price of bread over the previous century, he would have realized that his model was flawed.

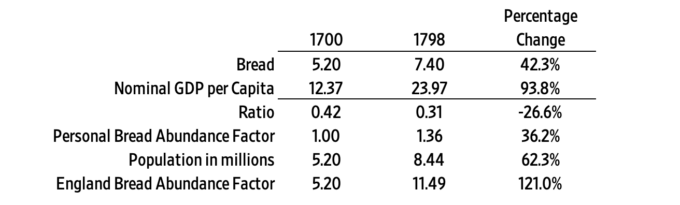

Between 1700 and 1798, the population of England increased from 5.2 million to 8.44 million, or 62.3 percent. Over the same period, nominal gross domestic product (GDP) per person per year increased from £12.37 to £23.97, or 93.8 percent, according to Appendix A in The Story of Bread by Ronald Sheppard and Edward Newton. The nominal price of a four-pound loaf of bread increased from 5.2p to 7.4p, or 42.3 percent. The ratio of bread to GDP per capita declined from 0.42 in 1700 to 0.31 in 1798 or 26.6 percent. See the Table below.

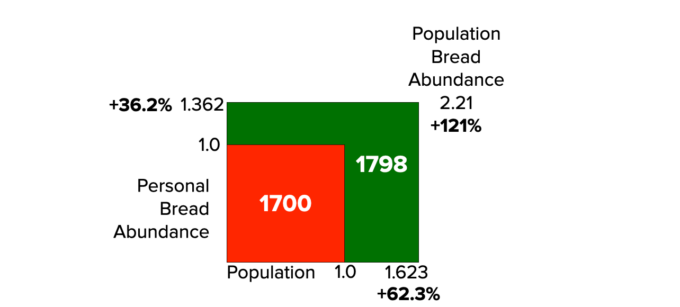

This suggests that for the time required to earn one loaf of bread in 1700, an Englishman would get 1.36 loaves in 1798. Bread had become 36.2 percent more abundant at the personal level (relevant equation is [(0.4204 ÷ 0.3087) – 1] = 0.362 = 36.2%).

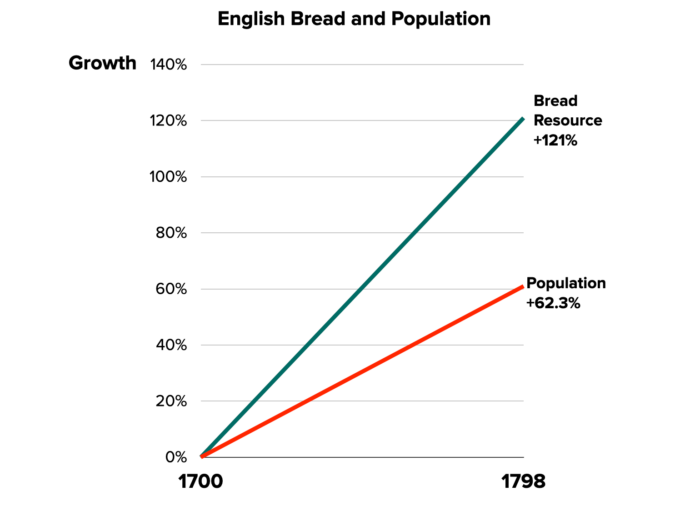

Bread abundance for the whole country is equal to personal bread abundance multiplied by population. As the population of England increased by 62.3 percent, bread became 36.2 percent more abundant, suggesting bread had become 121 percent more abundant for the country (relevant equation is [(1.362 x 1.623) – 1] = 1.21 = 121%). For every 1 percent increase in population, bread abundance was increasing 1.94 percent. See Figure 2.

As shown in Figure 3, the size of the English bread resource in 1798 was much higher than in 1700.

England began to enjoy more and more freedom to innovate in the 1700s. This innovation shows up in bread abundance. Humans are supremely adaptable and clever. If they have freedom, they will always create more resources for themselves and everyone else.

Lesson learned: Test your hypothetical models against reality. Maybe you’ll be much less frightened of the future.