Most of you think that the world, in general, is getting worse. You are wrong. Citing uncontroversial data on major global trends, I will prove to you that this dark view of humanity’s prospects is, in large part, badly mistaken.

First, though: How do I know most of you believe that things are bad and getting worse? Because that’s what you tell pollsters. A 2016 survey by the public opinion firm YouGov asked folks in 17 countries, “All things considered, do you think the world is getting better or worse, or neither getting better or worse?” Fifty-eight percent answered worse, and 30 percent chose neither. Only 11 percent thought things are getting better. In the United States, 65 percent thought that the world is getting worse and 23 percent said neither. Only 6 percent responded that the world is getting better.

A 2015 study in the journal Futures polled residents of the U.S., the U.K., Canada, and Australia; it reported that a majority (54 percent) rated the risk of our way of life ending within the next 100 years at 50 percent or greater, and a quarter (24 percent) rated the risk of humans being wiped out in the next 100 years at 50 percent or greater. Younger respondents were more pessimistic than their elders.

So why are so many smart people like you wrong about the improving state of the world? For starters, almost all of us have a couple of psychological glitches that cause us to focus relentlessly on negative news.

Way back in 1965, Johan Galtung and Mari Holmboe Ruge of the Peace Research Institute Oslo observed “a basic asymmetry in life between the positive, which is difficult and takes time, and the negative, which is much easier and takes less time.” They illustrated this by comparing “the amount of time needed to bring up and socialize an adult person and the amount of time needed to kill him in an accident; the amount of time needed to build a house and to destroy it in a fire, to make an airplane and to crash it, and so on.” News is bad news; steady, sustained progress is not news.

Smart people seek to be well-informed and so tend to be more voracious consumers of news. Since journalism focuses on dramatic events that go wrong, the nature of news thus tends to mislead readers and viewers into thinking that the world is in worse shape than it really is. This mental shortcut is called the availability bias, a name bestowed on it in 1973 by the behavioral scientists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman. “People tend to assess the relative importance of issues by the ease with which they are retrieved from memory—and this is largely determined by the extent of coverage in the media,” explains Kahneman in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Another reason for the ubiquity of mistaken gloom derives from evolutionary psychology. A Stone Age person hears a rustle in the grass. Is it the wind or a lion? If he assumes it’s the wind and the rustling turns out to be a lion, then that person does not live to become one of our ancestors. We are the descendants of the worried folks who tended to assume that all rustles in the grass were dangerous predators. Due to this instinctive negativity bias, most of us attend far more to bad rather than to good news.

Of course, not everything is perfect. Big problems remain to be addressed and solved. As the Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker says, “it’s essential to realize that progress does not mean that everything gets better for everyone, everywhere, all the time. That would be a miracle, that wouldn’t be progress.”

For example, man-made climate change arising largely from increasing atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide released from the burning of fossil fuels could become a significant problem for humanity during this century. The spread of plastic marine debris is a big and growing concern. Many wildlife populations are declining, and tropical forest area continues to shrink. And far too many people are still malnourished and dying in conflicts around the globe.

But many of those problems are already in the process of being ameliorated. For example, the falling prices of renewable energy sources offer ever-stronger incentives to switch away from fossil fuels. And hyperefficient agriculture is globally reducing the percentage of people who are hungry—while simultaneously freeing up land, so that forests are now expanding in much of the world.

The fact that we denizens of the early 21st century are much richer than any previous generation accounts for much of the good news. Thanks to technological progress and expanding global markets, the size of the world’s economy since 1820 has grown more than 100-fold while world population grew somewhat less than eightfold. In concrete terms, world gross product grew from $1.2 trillion (in 2011 dollars) to more than $116 trillion now. Global per capita GDP has risen from $1,200 per year in 1820 to more than $15,000 per person currently.

The astonishing result of this increase in wealth is that the global rate of absolute poverty, defined as living on less than $1.90 per person per day, fell from 84 percent in 1820 to 55 percent in 1950. According to the World Bank, 42 percent of the globe’s population was still living in absolute poverty as late as 1981. The latest World Bank assessment reckons that the share of the world’s inhabitants living in extreme poverty fell to 8.6 percent in 2018. In 1990 about 1.9 billion of the world’s people lived in extreme poverty; by 2018, that number had dropped to 660 million.

In Christian tradition, the four horsemen of Famine, Pestilence, War, and Death usher in the apocalypse. Compared to 100 years ago, deaths from infectious diseases are way down; wars are rarer and kill fewer people; and malnutrition has steeply declined. Death itself is in retreat, and the apocalypse has never looked further away.

Death

Average life expectancy at birth hovered around 30 years for most of human history. This was mostly due to the fact that about a third of all children died before they reached their fifth birthday. Demographers estimate that in 16th century England, 60 out of 100 children died before age 16. Some fortunate people did have long lives, but only 4 percent of the world’s population lived to be older than 65 before the 20th century.

In 1820, global average life expectancy was still about 30 years. Then, remarkably, life expectancy in Europe and North America began rising at the sustained rate of about 3 months annually. That was largely a consequence of better nutrition and the rise of public health measures such as filtered water and sewers.

During the past 200 years, global life expectancy more than doubled, now reaching more than 72, according to the World Bank. Worldwide, the proportion of folks who are 65 years and older has also more than doubled, to 8.5 percent. By 2020, for the first time in human history, there will be more people over the age of 64 than under the age of 5.

Even in the rapidly industrializing United States, average life expectancy was still only 47 years in 1900, and only 4 percent of Americans were 65 years and older. U.S. life expectancy is now 78.7 years. And today 15.6 percent of Americans are 65 or older, while only 6.1 percent are under age 5.

The historic rate of rising life expectancy implies a global average of 92 years by 2100. But the United Nations’ medium fertility scenario rather conservatively projects that average global life expectancy at the end of the century will instead be 83.

A falling infant mortality rate accounts for the major share of increasing longevity. By 1900, infant mortality rates had fallen to around 140 per 1,000 live births in modernizing countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States. Infant mortality rates in the two countries continued to fall to around 56 per 1,000 live births in 1935 and down to about 30 per 1,000 live births by 1950. In 2017, the U.K. and U.S. infant mortality rates were 3.8 and 5.9 per 1,000 live births, respectively. Since 1900, in other words, infant mortality in those two countries has fallen by more than 95 percent.

Infant mortality rates have also been falling steeply in the rest of the world. The World Health Organization estimates that the global infant mortality rate was just under 160 per 1,000 live births in 1950. In 2017, it was down to 29.4 per 1,000 live births, about the level of the U.K. and the U.S. in 1950. Vastly fewer babies are dying today because rising incomes have enabled improved sanitation and nutrition and more resources for educating mothers.

According to the World Bank, the global crude death rate stood at 17.7 per 1,000 in 1960. That is, about 18 people out of every 1,000 persons in a community would die each year. That number has fallen to 7.6 per 1,000 in 2016. The global death rate has fallen by more than half in the last 60 years.

Famine

Food production since 1961 has essentially quadrupled while global population has increased two and half times, according to the World Bank. As a result, the Food and Agriculture Organization reports, the global average food supply per person per day rose from 2,225 calories in 1961 to 2,882 calories in 2013. As a general rule, men and women need around 2,500 or 2,000 calories per day, respectively, to maintain their weight. Naturally, these values vary depending on age, metabolism, and levels of physical activity, among other things.

Food availability, of course, is not equally distributed across the globe. Nevertheless, rising agricultural production has caused undernourishment in poor developing countries to fall dramatically. The Food and Agriculture Organization regularly estimates the “proportion of the population whose habitual food consumption is insufficient to provide the dietary energy levels that are required to maintain a normal active and healthy life.” It reports that this undernourishment fell from 37 percent of the population in 1969–71 to just under 15 percent by 2002, reaching a low of 10.6 percent in 2015 before ticking up to 10.9 percent in 2017.

Famines caused by drought, floods, pests, and conflict have collapsed whole civilizations and killed hundreds of millions of people over the course of human history. In the 20th century, the biggest famines were caused by communist regimes in the Soviet Union and mainland China. Soviet dictator Josef Stalin’s famines killed up to 10 million people; China’s despot, Mao Zedong, starved 45 million between 1958 and 1962.

In the 21st century, war and political violence are still major causes of hunger around the world. Outbreaks of conflict in Syria, Yemen, Somalia, South Sudan, Afghanistan, and Nigeria are largely responsible for the recent uptick in the rate of global undernourishment. In other words, famines have disappeared outside of war zones. Much progress has been made, and the specter of famine no longer haunts the vast majority of humankind.

Pestilence

Prior to its eradication in 1979, smallpox was one of humanity’s oldest and most devastating scourges. The disease, which can be traced all the way back to pharaonic Egypt, was highly contagious. A 1775 French medical textbook estimated that 95 percent of the population contracted smallpox at some point during their lives.

In the 20th century alone, the disease is thought to have killed between 300 and 500 million people. The smallpox mortality rate among adults was between 20 and 60 percent. Among infants, it was 80 percent. That helps explain why life expectancy remained between 25 and 30 years for so long.

Edward Jenner, an English country doctor, noted that milkmaids never got smallpox. He hypothesized that the milkmaids’ exposure to cowpox protected them from the disease. In 1796, Jenner inserted cowpox pus from the hand of a milkmaid into the arm of a young boy. Jenner later exposed the boy to smallpox, but the boy remained healthy. Vacca is the Latin word for a cow—hence the English word vaccination.

The World Health Organization estimates that vaccines prevented at least 10 million deaths between 2010 and 2015 alone. Many millions more lives were protected from illness. As of 2018, global vaccination coverage remains at 85 percent, with no significant changes during the past few years. That said, an additional 1.5 million deaths could be avoided if global immunization coverage improves.

Improved sanitation and medicine account for many of the other wins against pestilence. Before the 19th century, people didn’t know about the germ theory of disease. Consequently, most people did not pay much attention to the water they drank. The results were often catastrophic, since contaminated water spreads infectious diseases, including diarrhea, dysentery, typhoid, polio, and cholera.

From 1990 to 2015, access to improved water sources rose from 76 percent of the world’s population to 91 percent. Put differently, 285,000 people gained access to clean water each day over that time period.

As a result of growing access to clean water and improved sanitation, along with the wider deployment of rehydration therapy and effective rotavirus vaccines, the global rate of deaths from diarrheal diseases stemming from rotavirus, cholera, and shigella has fallen from 62 per 100,000 in 1985 to 22 per 100,000 in 2017, according to The Lancet’s Global Burden of Disease study that year. And thanks to constantly improving medicines and pesticides, malaria incidence rates decreased by 37 percent globally and malaria mortality rates decreased by 60 percent globally between 2000 and 2015.

War

Your chances of being killed by your fellow human beings have also been dropping significantly. Lethal interpersonal violence was once pervasive. Extensive records show that the annual homicide rate in 15th century England hovered around 24 per 100,000 residents, while Dutch homicide rates are estimated as being between 30 and 60 per 100,000 residents. Fourteenth century Florence experienced the highest known annual homicide rate: 150 per 100,000. The estimated homicide rates in 16th century Rome range from 30 to 80 per 100,000. Today, the intentional homicide rate in all of those countries is around 1 per 100,000.

The Cambridge criminologist Manuel Eisner notes that “almost half of all homicides worldwide occurred in just 23 countries that account for 10 per cent of the global population.” Unfortunately, medieval levels of violence still afflict such countries as El Salvador, Honduras, and South Africa, whose respective homicide rates are 83, 57, and 34 per 100,000 persons.

Nonetheless, the global homicide rate is falling: According to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, it has dropped from 6.4 per 100,000 in 1990 to 5.3 per 100,000 in 2016. That’s a reduction of 17 percent during a remarkably short period of 26 years, or 0.7 percent per year.

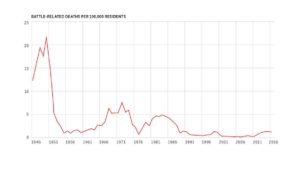

Another way to measure the general decline in violence is the global battle death rate per 100,000 people. Researchers at the Peace Research Institute Oslo have documented a steep post–World War II decline in the rate at which soldiers and civilians are killed in combat. The rate of battle deaths per 100,000 people reached a peak of 23 in 1953. By 2016, that had fallen by about 95 percent.

Apocalypse Later?

Some smart people acknowledge that considerable social, economic, and environmental progress has been made but worry that the progress will not necessarily continue.

“Human beings still have the capacity to mess it all up. And it may be that our capacity to mess it up is growing,” claims Cambridge political scientist David Runciman in The Guardian. He adds, “For people to feel deeply uneasy about the world we inhabit now, despite all these indicators pointing up, seems to me reasonable, given the relative instability of the evidence of this progress, and the [unpredictability] that overhangs it. Everything really is pretty fragile.”

Runciman is not alone. The worry that civilization is just about to go over the edge of a precipice has a long history. After all, many earlier civilizations and regimes have collapsed, including the Babylonian, Roman, Tang, Mayan, and, more recently, Ottoman and Soviet empires.

Yet there are good reasons for optimism. In their 2012 book Why Nations Fail, economists James Robinson of the University of Chicago and Daron Acemoglu of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology persuasively outline an explanation for the exponential improvement in human well-being that started about two centuries ago.

Before then, they argue, most societies were organized around “extractive” institutions—political and economic systems that funnel resources from the masses to the elites. In the 18th century, some countries—including Britain and many of its colonies—shifted from more extractive to more inclusive institutions.

“Inclusive economic institutions that enforce property rights, create a level playing field, and encourage investments in new technologies and skills are more conducive to economic growth than extractive economic institutions that are structured to extract resources from the many by the few,” the authors write. “Inclusive economic institutions are in turn supported by, and support, inclusive political institutions.”

Inclusive institutions are similar to one another in their respect for individual liberty. They include democratic politics, strong private property rights, the rule of law, enforcement of contracts, freedom of movement, and a free press. Inclusive institutions are the bases of the technological and entrepreneurial innovations that produced a historically unprecedented rise in living standards in those countries that embraced them, including the United States, Western Europe, Japan, and Australia.

While uneven and occasionally reversed, the spread of inclusive institutions to more and more countries is responsible for what the University of Illinois at Chicago economist Deirdre Nansen McCloskey calls the “Great Enrichment,” which has boosted average incomes 10- to 30-fold in those countries where they have taken hold.

The most striking examples of social disintegration—Roman, Tang, Soviet—occurred in extractive regimes. Despite crises such as the Great Depression, there are no examples so far of countries with long-established inclusive political and economic institutions suffering similar collapses.

In addition, major confrontations between relatively inclusive regimes and extractive regimes, such as World War II and the Cold War, have been won by the former. That suggests that liberal free market democracies harbor reserves of resilience that enable them to forestall or rise above shocks that destroy countries with brittle extractive systems.

If inclusive liberal institutions can continue to be strengthened and if they further spread across the globe, the auspicious trends documented here will extend their advance, and those that are currently negative will turn positive. By acting through inclusive institutions to increase knowledge and pursue technological progress, past generations met their needs and hugely increased our generation’s ability to meet our needs. We should do no less for future generations. That is what sustainable development looks like.

This article is based on data and analysis drawn from the author’s forthcoming book Ten Global Trends Every Smart Person Should Know (Cato), co-authored with HumanProgress.org editor and Cato Institute Senior Policy Analyst Marian L. Tupy.

This first appeared in Reason.