This article was originally published at Pessimists Archive on 12/1/2023.

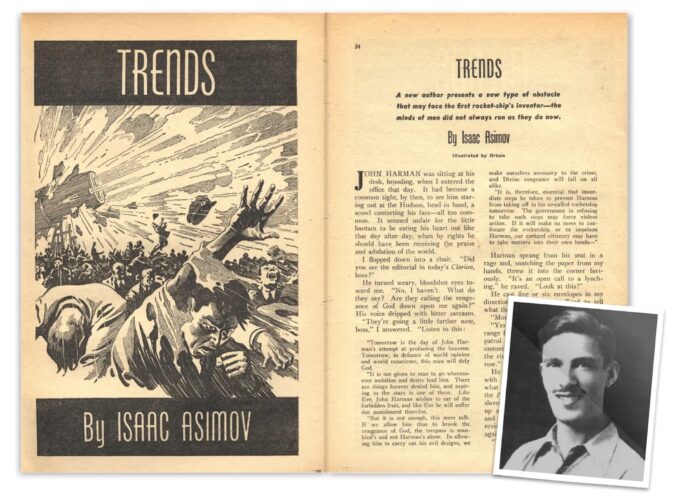

In 1938, an 18-year-old Isaac Asimov penned one of his first science fiction tales, envisioning man’s maiden voyage into space – with a twist.

The short story told the tale of a technologist pushing humanity to intimidating new heights while facing opposition from a technophobic movement warning of existential doom. One employee – persuaded by their rhetoric – tries to destroy the company in the name of saving humanity.

Remind you of anything?

The story – titled “Trends” – centres around tech-entrepreneur John Harman, a man driven by a singular mission: launching the first person into space aboard his rocket ‘The Prometheus‘ – a fitting name considering its reception.

A campaign of fierce opposition is lead by neo-luddite revivalist Otis Eldredge, founder of the 20 million strong ‘League of the Righteous.‘ Eldredge vehemently denounces Harman’s endeavour as a “blasphemous attempt to breach a realm humanity is forbidden to explore.” On the day of lift-off, Eldredge attends, followers in tow to protest, to issue a dire warning:

The finger of God is upon you, John Harman. He shall not allow His works to be defiled. You die today, John Harman.

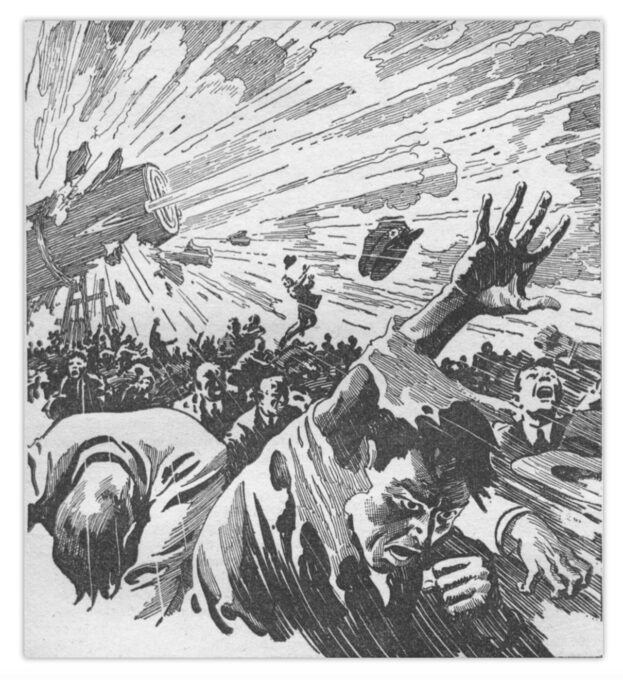

The Prometheus – just before lift off – explodes on the launchpad, a moment illustrated on the pages of ‘Astounding Science Fiction’ the magazine Trends first appeared.

The cause? Sabotage by an employee – incited by Eldridge – in the name of saving humanity. Newspapers would report on the incident with damning headlines like “28 killed, 73 Wounded – the Price of Sin.” Eldridge would be injured in the blast, in turn his followers would form mobs in search of Harman. One of the fatalities – the treacherous saboteur – would make a proud confession in his final breaths:

I did it. I broke open the liquid-oxygen compartments and when the spark went through the acetylide mixture the whole cursed thing exploded.

The explosion saw Harman thrown into exile and hiding – where he would covertly begin efforts to build a new ship to try and reach space once again. Space travel would be prohibited in the wake of the disaster and the proceeding years would see Otis Eldridge and his movement gain political power, leading to the creation of the ‘Federal Scientific Research Investigatory Bureau’ (FSRIB.) Any and all scientific research had to be approved by it. Eventually the FSRIB would pass a blanket ban on all scientific research. This, the climax of what came to be know as the “Neo-Victorian Age.“

Eldridge would say at the time “Science has gone too far,” declaring that “We must halt it indefinitely, and allow the world to catch up.” According to him, this, and trust in god was the only way to “achieve universal and permanent prosperity.”

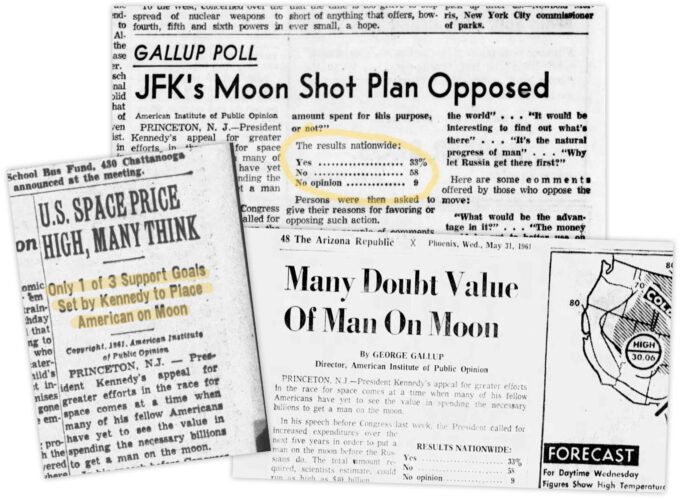

Trends was prescient, not technologically – space travel was a cliche vision of the future by then. Its foresight was sociological and political. Asimov had predicted popular opposition to space flight 25 years before Kennedy’s moonshot announcement was met with 33% approval ratings (an often forgotten fact we explored here).

The idea that a meaningful number of people would oppose space exploitation – such a bold and inspiring prospective fear – was hard to imagine in 1938. A possibility that Asimov would say in retrospect:

It never occurred to anybody that there might actually be resistance to the whole notion; people might think it was a rotten idea and a waste of money.

It was a unique twist in a genre that often assumed technological advance was eagerly embraced by society – at least initially. This – Asimov would later say – is the reason Trends got published: it was something the editor had “never seen before” in an era of space stories depicting “oyster men” fighting “heroes” who end up marrying a “beautiful princess who lays eggs” – Asimov joked.

The predictive power of ‘Trends’ continues to grow, 80 years later, private Space pioneers – akin to John Harman – receive scorn from some for daring to ‘pierce the veil beyond’ in their very own ‘Prometheus’ rockets. While not as extreme or effective, their critics – including Neil Armstrong himself – certainly reflect Asimov’s forecasts with regards to impassioned opposition. And in 2023, a dramatic attempted boardroom coup at OpenAI, strongly mirrored the treachery of Harman’s radicalized employee: it was reportedly inspired by concerns of existential risk from AI. (One OpenAI board member likened the companies possible destruction to a net-positive for humanity.)

Asimov’s Awakening

In 1974, Asimov would recall his prescient forecast in a speech titled ‘The Future of Humanity’ – telling an audience they were entitled to ask how a naive 18-year old boy “could see something clearly that older and thicker heads failed to see.” The answer he said, was not that he was a genius or an oracle, rather he’d been exposed to the often forgotten history of technological pessimism as an under-graduate at Columbia University. This experience lead to an epiphany which he eloquently recalled:

I discovered, to my amazement, that all through history there had been resistance…and bitter, exaggerated, last-stitch resistance…to every significant technological change that had taken place on earth.

This moment of enlightenment came for Asimov while struggling to make ends meet as a Columbia University student, when he would get temp work for sociologist Ber…

This moment of enlightenment came for Asimov while struggling to make ends meet as a Columbia University student, when he would get temp work for sociologist Bernhard J. Stern, helping research a book on social resistance to technological change, later titled “Society and Medical Progress.”

This work exposed him to many historical examples of opposition to scientific and technological progress, specifically in the field of medicine. In the days before CMD + F and Xerox, Asimov had to locate books in a library “Turn to the pages where I was to find the reference” and then “copy them out longhand” as part of the job. It was this experience that opened his eyes to the perennial nature of tech-pessimism and its sociological, psychological and political motivations, recalling:

when I read all of these references I discovered, to my amazement, that all through history there had been resistance…and bitter, exaggerated, last-stitch resistance…to every significant technological change that had taken place on earth. Usually the resistance came from those groups who stood to lose influence, status, money…as a result of the change. Although they never advanced this as their reason for resisting it. It was always the good of humanity that rested upon their hearts.

Asimov would go on to cite examples of stage coaches being opposed by canal owners, who warned people wouldn’t be able to breath at such speeds, and how eventually the stagecoach owners memorized and deployed the same arguments when railroads were developed. (we have found similar arguments made about planes and automobiles too, see below.)

Asimov had noticed a pattern and after months of being exposed to these rhythms of history, he said to himself quote: “I can make a syllogism out of this” which he formulated as follows:

Major Premise: All technological changes meet resistance.

Minor Premise: Space Travel represents a technological change.

Conclusion: There will be resistance to space travel.

Asimov would say once formulated, he “wrote the story and sold it” joking “and here I am, a genius at having foreseen this.”

This syllogism – one we know well – inspired the unique plot of Trends. By combining history fact with science fiction, Asimov wrote a timeless story with perennial forecasting power: not about robots and technology, but about human beings, psychology and sociology. This would also shape his proceeding works to a great degree: such as the first short story in ‘I, Robot’ that told a tale of a little girl befriending a house robot, her technophobic mother taking it away and that same robot eventually saving the girls life. A kind of reverse Black Mirror and a far cry from the Hollywood movie that borrowed its name.

Asimov’s Mistake

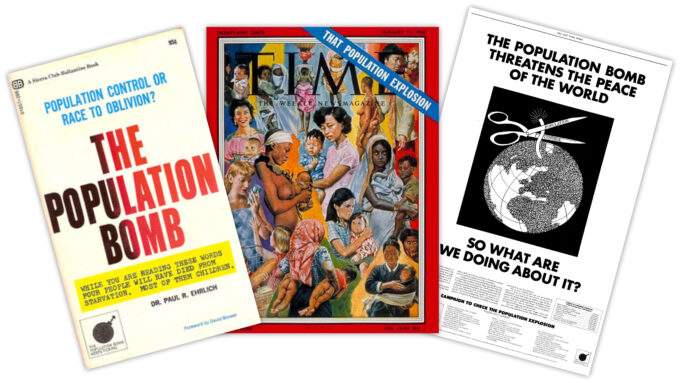

Ironically, the next part of Asimov’s 1973 speech concerned what is now a cynical trope: he would warn about global population growth and our ability to keep up with it, suggesting reducing the birth rate was needed to avoid disaster.

This concept was popularized in the 1970s by Paul Ehrlich’s 1968 ‘The Population Bomb’ and was – ironically – just the kind of cynical resistance to civilisational development Asimov was decrying just moments earlier.

Ehrlich and Asimov turned out to be wrong, because they didn’t have enough faith in technological progress and human ingenuity. History might be a great inoculation against ignorant fears of civilisational development, but it doesn’t offer total protection. Asimov proves, no one is immune.

A Neo-Victorian Age

Ehrlich’s book was one of many that decade which precipitated the decline of post-WWII optimism, giving way to a ‘de-growth’ mindset, the kind seen in the aftermath of John Harman’s promethean effort to put man in space.

Ironically it was the 1968 Apollo 8 mission and its famous ‘Earth Rise’ photo, that would recast the planet as a borderless, fragile blue dot – helping birth the modern environmental movement. A movement that certainly has merit in regards to highlighting the problems of man-made global warming, O-Zone depletion and other negative externalities of technology. However, it also had a proclivity to treat technology as anathema to nature – the same way Otis Eldridge treated it as an affront to God.

Some would argue the previous 50 years has – in some ways – mirrored the “Neo-Victorian Age” featured in Trends. One of reactionary opposition, over-precaution and over-regulation that saw scientific, technological and civilisational development needlessly stymied – leading to a “Great Stagnation.” Some evidence cited for this: the cancellation of America’s Boeing 2707 supersonic jet project in 1971 and Concord in 2001. Opposition to nuclear power, that saw Nixon’s 1973 proposal to build a 1000 nuclear power plants by the year 2000, abandoned. As well as the emergence of Genetic Engineering being met with mass opposition, with some framing it as an affront to the natural world and others – like Eldridge – using religious language (Jeremy Rifkin’s 1977, “Who Should Play God?“) This resulted in multi-year moratoriums in Europe and prohibition that in some cases has cost millions of lives in the developing world. And don’t forget the aforementioned fallout from the over-population panic and the latest quasi-religious rhetoric around Artificial Intelligence.

Asimov’s Archetype

In the opening pages of Trends Asimov would foretell such a post-WW2 future marred by misanthropy, with John Harman mourning the techno-optimism of yesteryear:

those were the days when science flourished. Men were not afraid then; somehow they dreamed and dared. There was no such thing as conservatism when it came to matters mechanical and scientific. No theory was too radical to advance, no discovery too revolutionary to publish. Today, dry rot has seized the world when a great vision, such as space travel, is hailed as “defiance of God.”

Unlike most modern science fiction narratives like Jurassic Park, Terminator and Blackmirror – Trends grappled with a dangerous misaligned general intelligence: human beings fearing technology.

A science fiction, inspired by history fact: where technological-stagnation creates a more dystopian future, rather than technological acceleration.

Sadly it is an archetype as rare today as it was in 1938.