Today marks the 41st installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org titled Heroes of Progress. This bi-weekly column provides a short introduction to heroes who have made an extraordinary contribution to the well-being of humanity. You can find the 40th part of this series here.

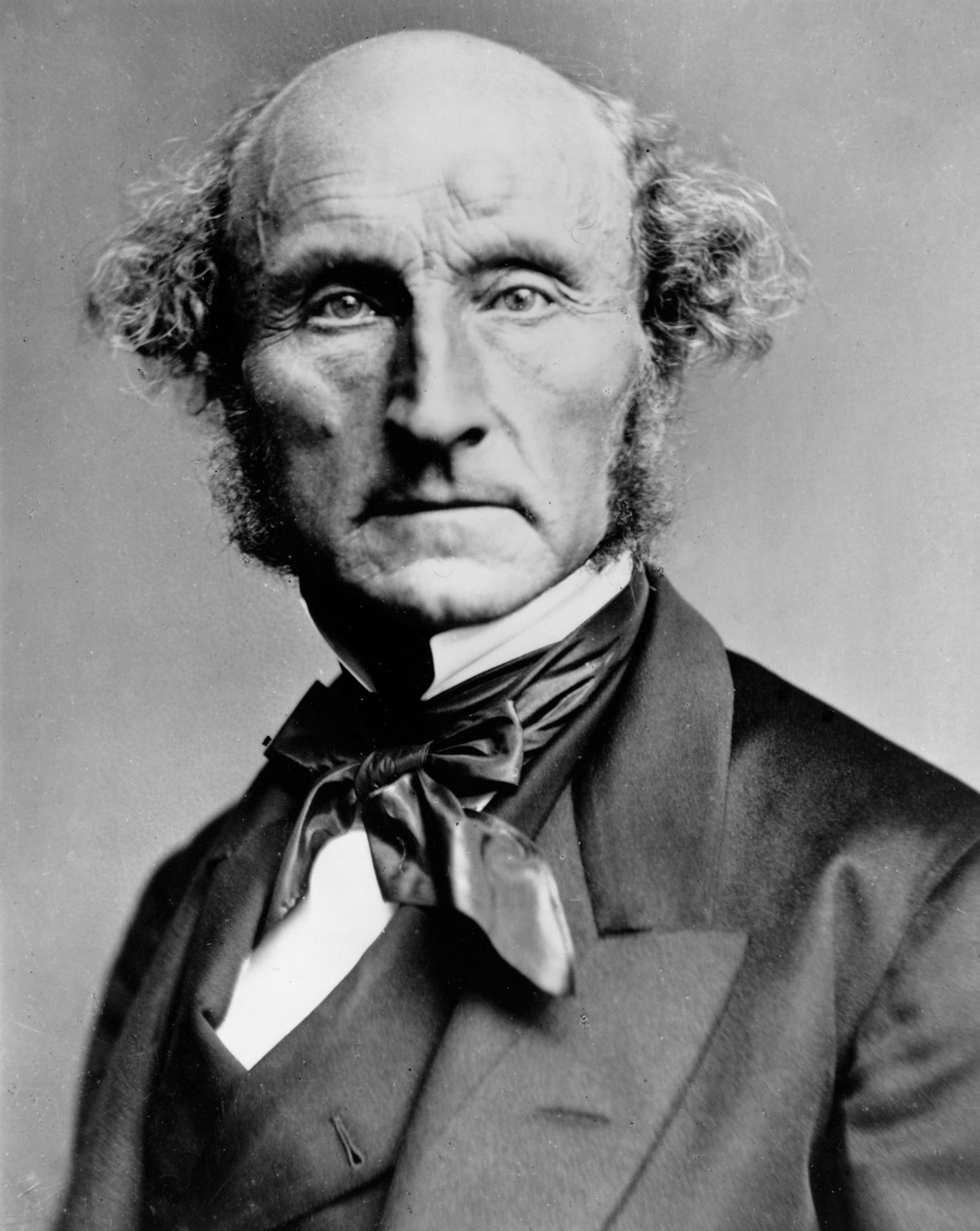

This week, our hero is John Stuart Mill – a 19th century English philosopher, parliamentarian and political economist. Throughout his life, Mill advocated for greater freedom of expression and the abolition of slavery. As a Member of the British Parliament, Mill presented the House of Commons with the first mass petition in favor of women’s suffrage. The petition inspired the creation of numerous suffragette campaigns throughout the world. One of Mill’s greatest contributions to philosophy was his harm principle, which holds that an action of a person should only be legally prohibited if it causes harm to other individuals. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy has dubbed him “the most influential English-speaking philosopher of the nineteenth century.”

John Stuart Mill was born on May 20th, 1806 in London, England. His father, James Mill, was a close friend to our 40th Hero of Progress, Jeremy Bentham. Mill had an extraordinary upbringing and his father educated him with the intention of creating an intellectual genius who would be equipped to lead the next generation of radical and utilitarian thinkers.

At the age of three, the younger Mill began learning ancient Greek. At eight years old, Mill was learning Latin. By the age of twelve, it is said that he had read most of the classical canon. Other than his siblings, Mill was deliberately prevented from associating with children his own age. It is said that, for amusement, Mill would often read treatises on experimental science.

In 1820, Mill took a year-long trip to France, where he stayed with the family of Samuel Bentham, the brother of Jeremy Bentham. The extracts from the diary that he kept at the time show that Mill spent his time in France meticulously studying chemistry, math and the French language. On his return to Britain in 1821, Mill began studying Roman Law with the renowned English legal theorist John Austin. He began studying political economy with David Ricardo – one of history’s most influential classical economists.

As a nonconformist (i.e., a Protestant who did not belong to the Church of England), Mill was not eligible to enroll at the University of Oxford or the University of Cambridge. In 1823, seventeen-year-old Mill decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and began working for the East India Company.

Mill stayed at the British East India Company for more than 35 years – first as an assistant examiner. Then, following the death of his father in 1836, Mill became responsible for the company’s relations with the Indian states. Although the work that Mill completed in his day job had little historical significance, the role allowed him plenty of time for his personal writings.

After 21 years of friendship, Mill married Harriet Taylor in 1851. She was a philosopher and women’s rights advocate. In 1858, the East India Company was dissolved. The newly unemployed Mill moved to Avignon, France, where he continued to write fulltime. In 1859, Mill published one of his best-known works, titled On Liberty. He dedicated the book to Taylor, who died the year before. He acknowledged her as a huge influence on his thinking and especially on his views pertaining to women’s rights.

On Liberty focuses on the nature and limits of the power that governments can rightfully exercise over an individual. The extent of a government’s power, Mill argued, should be based on the harm principle, which holds that “the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.”

In On Liberty, Mill also argues that freedom of speech is a necessary condition in order for a society to make intellectual and social progress. Mill believed that society can never be sure that a banned opinion does not contain at least some elements of truth. As such, people should be free to state any opinion they wished. Mill argued that even if a given opinion is false, individuals are more likely to abandon their incorrect views through open discourse. He noted that the truth itself can be better understood and prevented from becoming mere dogma if individuals continuously re-examined their beliefs. The book was an enormous success and Mill soon became a well-known public intellectual.

In 1861, Mill completed an essay titled The Subjection of Women. Published in 1869, the essay argued for the complete equality of the sexes. Mill believed that the oppression of women was a relic from ancient times and “one of the chief hindrances to human improvement.” The essay made Mill one of the earliest male proponents of gender equality. In the essay, Mill also expressed his opposition to slavery and his support for its abolition in the United States.

In the same year, Mill also published Considerations on Representative Government, in which he advocated for proportional representation, the single transferable vote, and the extension of suffrage to women.

In 1863, Mill published Utilitarianism. The book is a strong defense of utilitarian ethics – a philosophy that, according to Mill, suggests “that actions are right in the proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness.” Like Bentham, Mill argued there should be legislation favoring animal welfare and that the economic system of free markets was preferable to a planned economy.

In 1865, the Liberal party asked Mill to become its candidate for Member of Parliament for Westminster. Mill agreed to the Liberal Party’s offer on the condition that he would not canvass or financially contribute to his campaign. He also stated that if he were elected, he would not speak for local interests and instead use his position in Parliament to “serve as the conscience of his society.” He would, he said, go on supporting women’s suffrage.

Despite his lack of campaigning, Mill was successful in the election and he used his time in Parliament to advocate for land reform in Ireland, compulsory education for all, and perhaps most importantly, women’s rights. In 1866, Mill presented a petition to Parliament of more than 1,500 signatures that had been collected by the Women’s Suffrage Committee in favor of female enfranchisement.

In 1866, the Second Reform Act (i.e., a bill designed to expand the electorate by loosening the property qualifications) was debated in parliament. Mill used the Second Reform Act as an opportunity to try and introduce equal voting rights for men and women by proposing an amendment to the act that replaced the instances of “man” with “person.” This change would have enfranchised some property-owning women.

Unfortunately, the amendment was defeated. However, Mill’s advocacy caused immense debate surrounding women’s suffrage and inspired the creation of several political campaigns for female enfranchisement. Mill later described the amendment as “perhaps the only really important public service I performed in the capacity as a Member of Parliament.”

In the general election of 1868, Mill was not re-elected, and he returned to France to study and write. On May 8, 1873, Mill died of erysipelas in Avignon, France and his body was buried alongside his wife’s.

John Stuart Mill is remembered as one of the most important and influential philosophers of the 19th century. His enormous body of work continues to shape political thought and discourse. Mill’s advocacy of women’s rights, the harm principle and freedom of speech have helped to create less tyrannical and more egalitarian laws in many nations across the world. It is for these reasons that John Stuart Mill is our 41st Hero of Progress.