Summary: Proponents of the “great stagnation” narrative believe that progress has slowed down since the 1970s, with the exception of digital technology. This pessimistic view underestimates how small, cumulative improvements have transformed global wellbeing in the 21st century.

“Take away styles and fashion—and the computer screens,” said mathematician Eric Weinstein in a recent interview, “how do you know you’re not in 1973?”

The observation is classic for pointing to the slowing down of inventions that radically improve our lives. It does carry some punch: at least in the West, most major improvements over recent decades seem to have happened through computers and what their screens have allowed us to do—communication, internet, streaming, and globally expanding supply chains. That’s nothing to sweep under the rug, but let’s play along.

When venture capitalist Peter Thiel, in a famous lecture, complained about the lack of revolutionary inventions, he said, “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.” Symptomatically, the last few years have involved endless Twitter debacles, with prominent personalities banned, information manipulated, and Elon Musk’s expensive takeover. Ten years after Thiel’s complaint, we’re still arguing over Twitter—and we still don’t have flying cars.

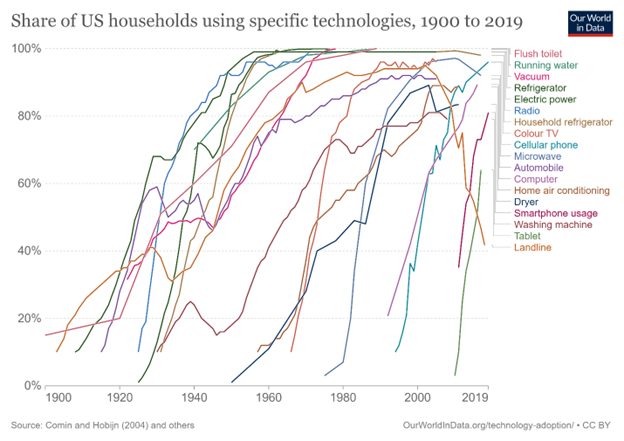

One of the most famous curves in 20th-century economic history is the speed at which new household gadgets were adopted. From flush toilets to radios to refrigerators to TVs and microwaves, it took only a few decades for these technologies to become used by everyone. A world with these household appliances is incomparably different from one without them.

We can draw similar curves with cars, energy usage, airplane passengers, or availability of goods and services; over the 20th century, everything just exploded upward. Compared with that, what does the 21st century have to show for itself?

The innocent-looking “aside from screens” is cheating, considering that so many of the worldly improvements in the past few decades were powered by the wide diffusion of screens, their communication capabilities, and the real-world economic change they allowed. Involved in every improvement from construction designs to airplane safety, from competitive price pressures to the ability to source goods from afar lies a computer, its network, or software. The internet gives us cheaper entertainment, the conveniences of e-commerce, and the ability to see and speak with loved ones across the globe.

Even so, in a Wall Street Journal opinion piece from February 2023, the Canadian energy researcher Vaclav Smil laments the pitiful growth in “fundamental economic activities on which modern civilization depends for its survival—agriculture, energy production, transportation and large engineering projects. Nor do we see rapid improvements in areas that directly affect health and quality of life, such as new drug discoveries and gains in longevity.” That which matters isn’t growing fast enough.

Before this or that counterexample springs to mind, Smil’s point isn’t that we have had zero improvements, but that the improvements we’ve had are comparatively minor: a few percentages here and another few there—nothing like the burst of change we had between, say, 1870 and 1970.

Noted Smil in a previous book, “as recently as the early decades of the 19th century, the existential foundations of a great European nation (feeding of the post-Napoleonic Bourbon France) rested on manual spreading of dung!” The life of an urban Frenchman two generations later, with electric light, cobbled streets, and household appliances, is incomparably better. An indescribable change in world affairs separates the early 19th century from the mid-20th century, a rate of change that we have never achieved since.

Are the pessimists right?

From time to time, pessimistic takes on the rate of progress come into fashion. Equipped with impressive books like Robert Gordon’s The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War and Tyler Cowen’s Average Is Over: Powering America Beyond the Age of the Great Stagnation, the case for a slowdown in economic growth and technology is persuasive.

The first reflection is to lift the perspective to a global scale. The orders-of-magnitude improvements that middle-class families in the West experienced during the 20th century are quickly underway in other parts of the world. Some 60 percent of Indonesian households now have refrigerators; almost all of India has access to electricity (though the quantities may still lag the rich world).

Another point is that living standards involve more components than the material appliances around us. The steepness of adoption curves in the early 20th century is mirrored by the worldwide decline of child mortality and (absolute) poverty over the past 50 years or so. Those are valuable improvements we should acknowledge.

While planes haven’t gotten faster in the past 50 years, they’ve become much safer, much more affordable, and (government regulations and TSA hassle aside) more convenient.

Gordon himself opens the preface of his doorstop of a book with, “The book is a readable flashback to another age when life and work were risky, dull, tedious, dangerous, and often either too hot or too cold in an era that lacked not just air conditioning but also central heating.” It’s not just the gadgets that account for that change, but improvements in communications, institutions, organizations, and expanded division of labor.

A more historically based observation is to note the revolutionary nature of small changes adding up—or, technically, multiplying up. Compared with the explosive growth in innovations and technologists’ dreams that always seem to outstrip reality, standard-of-living improvements are a lesson in compound growth. Over time, small changes revolutionize the world. If, as Smil reports in his Wall Street Journal article, batteries over the long haul improve by 2 percent a year, efficiency in energy production improves by 1.5 percent, and energy use in steel production falls by about 2 percent a year, a battery-powered steel device (ignoring other inputs) would improve a little more than 5 percent every year. That’s a doubling in 15 years. Negligible changes in the short run make for astronomical differences in the long run.

In the opening of A Culture of Growth, Gordon’s colleague at Northwestern University, Joel Mokyr, describes the unmatched importance of the industrial revolution: “The British Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth century unleashed a phenomenon never before even remotely experienced by any society.” The best estimates from that time suggest that economies’ real GDP advanced by 1.5 percent between 1760 and 1830, rising to about 2.5 percent during the later 19th century (0.5 percent and 1 percent, respectively, when we account for a growing population).

The improvements in material well-being over the world’s most extraordinary event were in the range of what Smil describes. The modern world was literally made in the low single digits of cumulative improvement, repeated over generations.

So, how do we know that we’re not in 1973 anymore? Because many more of us live longer, can travel farther, and can afford more things, have more, and further our education, and are less likely to die from disease, accidents, or circumstance. That’s less tangible than a refrigerator, but just as real.