Since Nicolas Maduro was sworn into his second term as President of Venezuela in January 2019, stories of civil unrest and economic hardship from the small Latin American country have dominated the media headlines. In the build up to his controversial re-election, Maduro prevented opposition parties from freely and fairly competing for public support. Because of those electoral shenanigans and the human rights violations that followed, most Venezuelan citizens, as well as most Western governments, refuse to recognize Maduro’s legitimacy as President.

As widespread protests continue into their fourth month, one thing has become very clear: Venezuela’s experiment with socialism has been a resounding failure. The annual inflation is more than 80,000 percent and it is estimated that almost 90 percent of Venezuelans now live in poverty. Mass food shortages mean that the average Venezuelan has lost over 11kg in weight, despite Maduro’s waistline continuing to expand. The government’s murder squads fanned out throughout the capital, assassinating the ruling regime’s opponents. However, it’s important to remember that conditions in Venezuela haven’t always been this tragic.

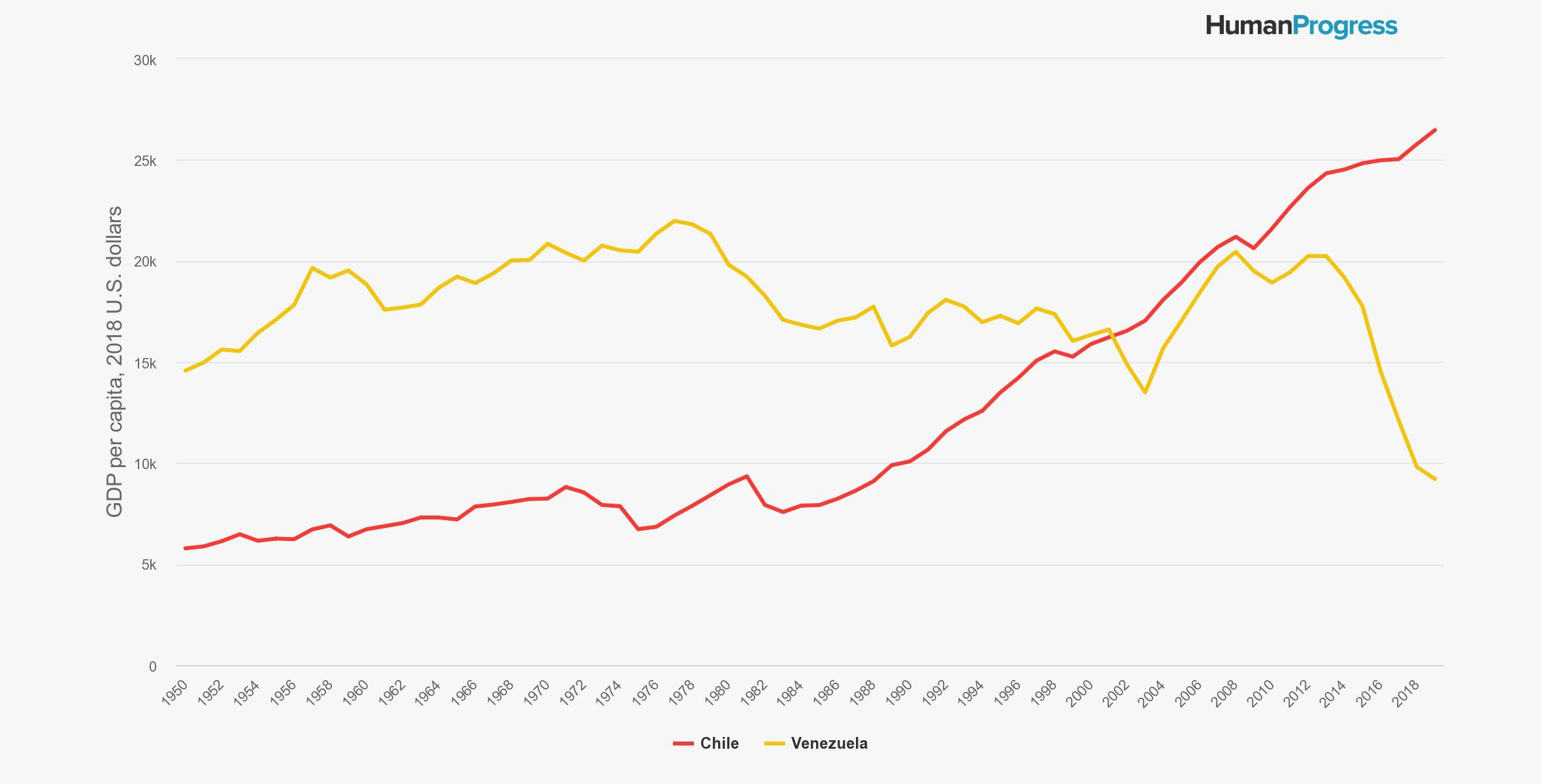

Between 1958 and 1999, Venezuela was a democracy – albeit an imperfect one. The country suffered from corruption, but Venezuelans did not face food shortages or experience widespread human rights abuses. By regional standards, Venezuela also had a relatively free-market economy. In the early 1950s, Venezuela’s gross domestic product per capita was among the highest in the world. It was higher than that in the United States and three times as high as that in Chile. Up until 1982, Venezuela was the richest country in Latin America.

To fully appreciate Venezuela’s decline, it is useful to compare its fate to the massive political and economic improvements experienced by the people of Chile.

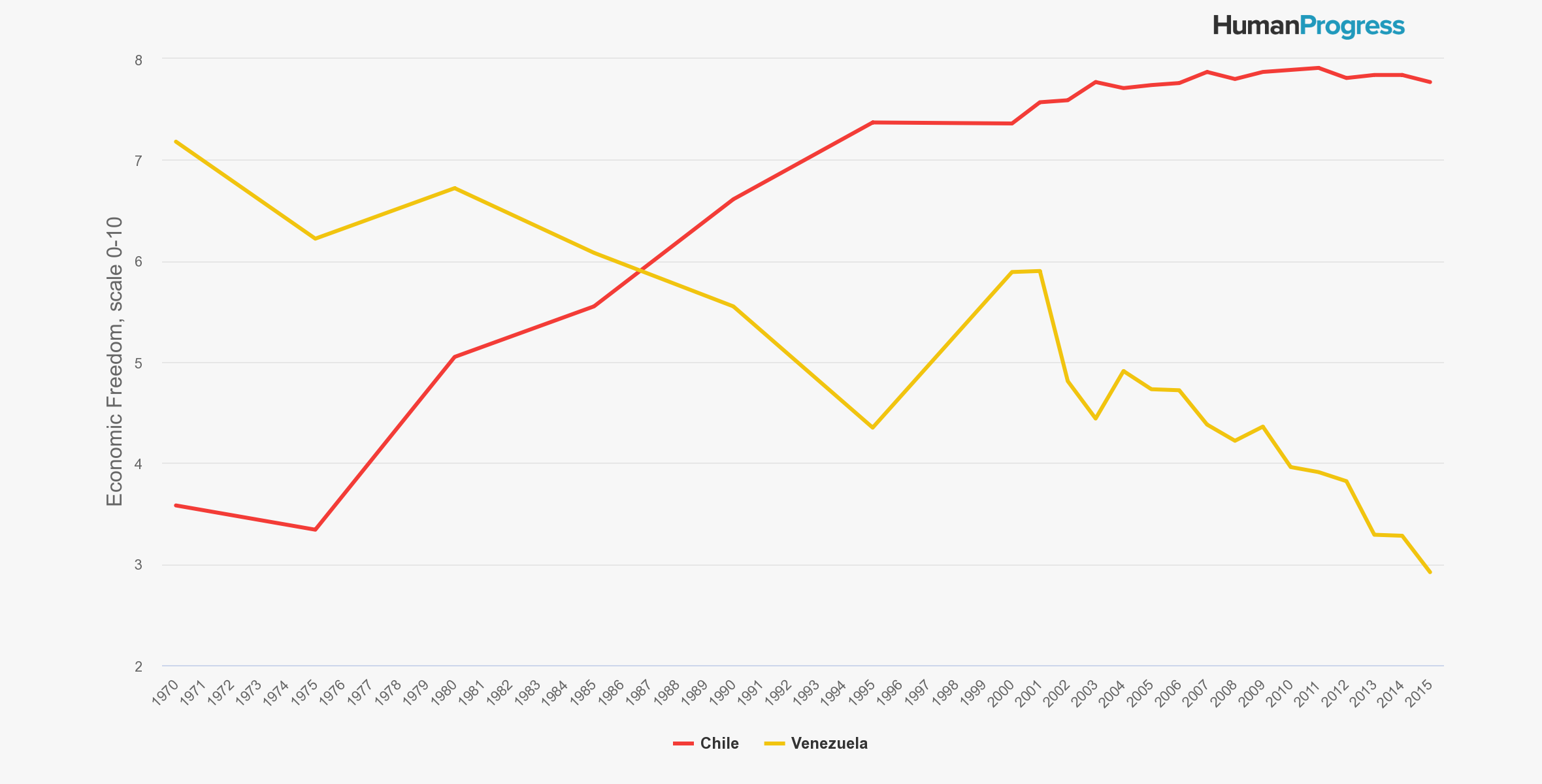

The story of Chile’s success starts in the mid-1970s, when the country’s government abandoned socialism and started to implement economic reforms. In 2016, Chile was the world’s 15th freest economy. Venezuela, in the meantime, declined from being the world’s 15th freest economy in 1975 to being the world’s least free economy in 2016 (Human Progress does not have data for the notoriously unfree North Korea).

As Chile’s economic freedom increased, so did income per capita (adjusted for inflation and purchasing power parity), which rose from being 32 percent of that in Venezuela in 1975, to being 287 percent of that in Venezuela by 2019. Between 1975 and 2019, the Chilean economy grew by 293 percent. Venezuela’s shrunk by 54 percent.

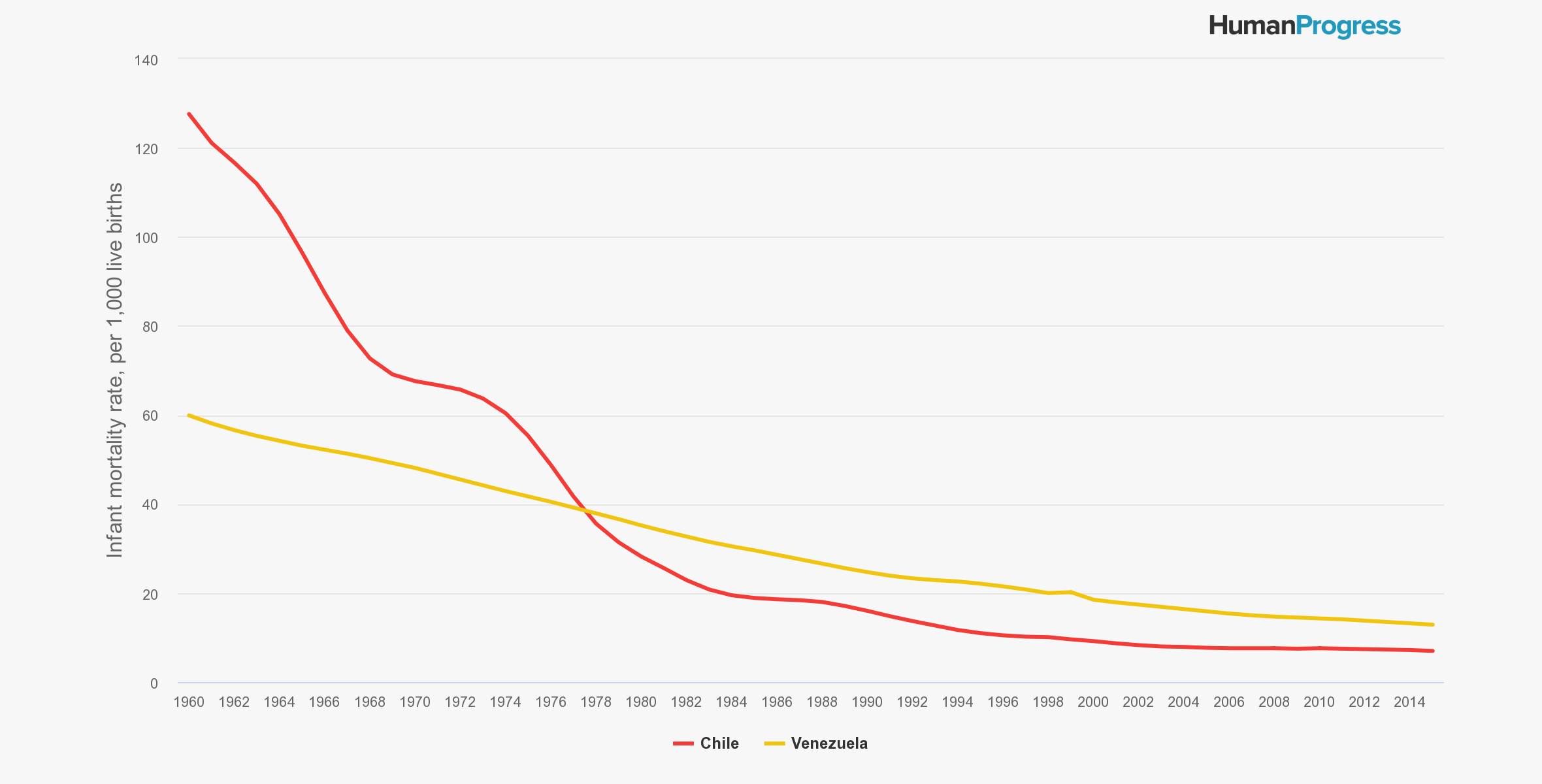

As its economy expanded, so did Chile’s ability to provide good healthcare for its people. In 1975, Chile’s infant mortality rate was 29 percent higher than Venezuela’s. By 2017, four times more infants died per 1,000 live births in Venezuela than in Chile.

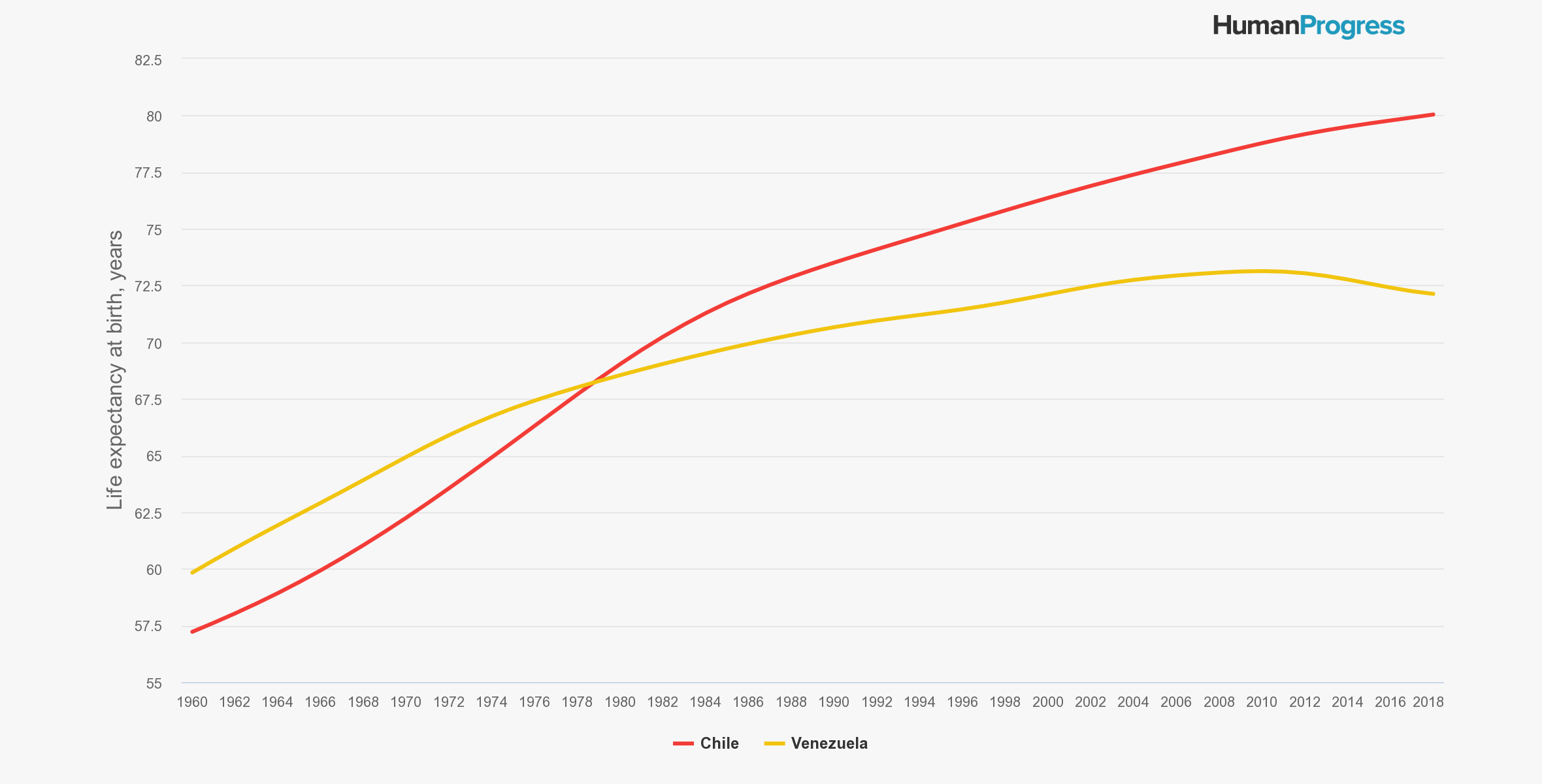

With declining infant mortality and improving standard of living came a steady increase in life expectancy. In 1975, Venezuelans lived longer than Chileans. In 2017, a typical Chilean lived over 5 years longer than the average citizen of the Bolivarian Republic.

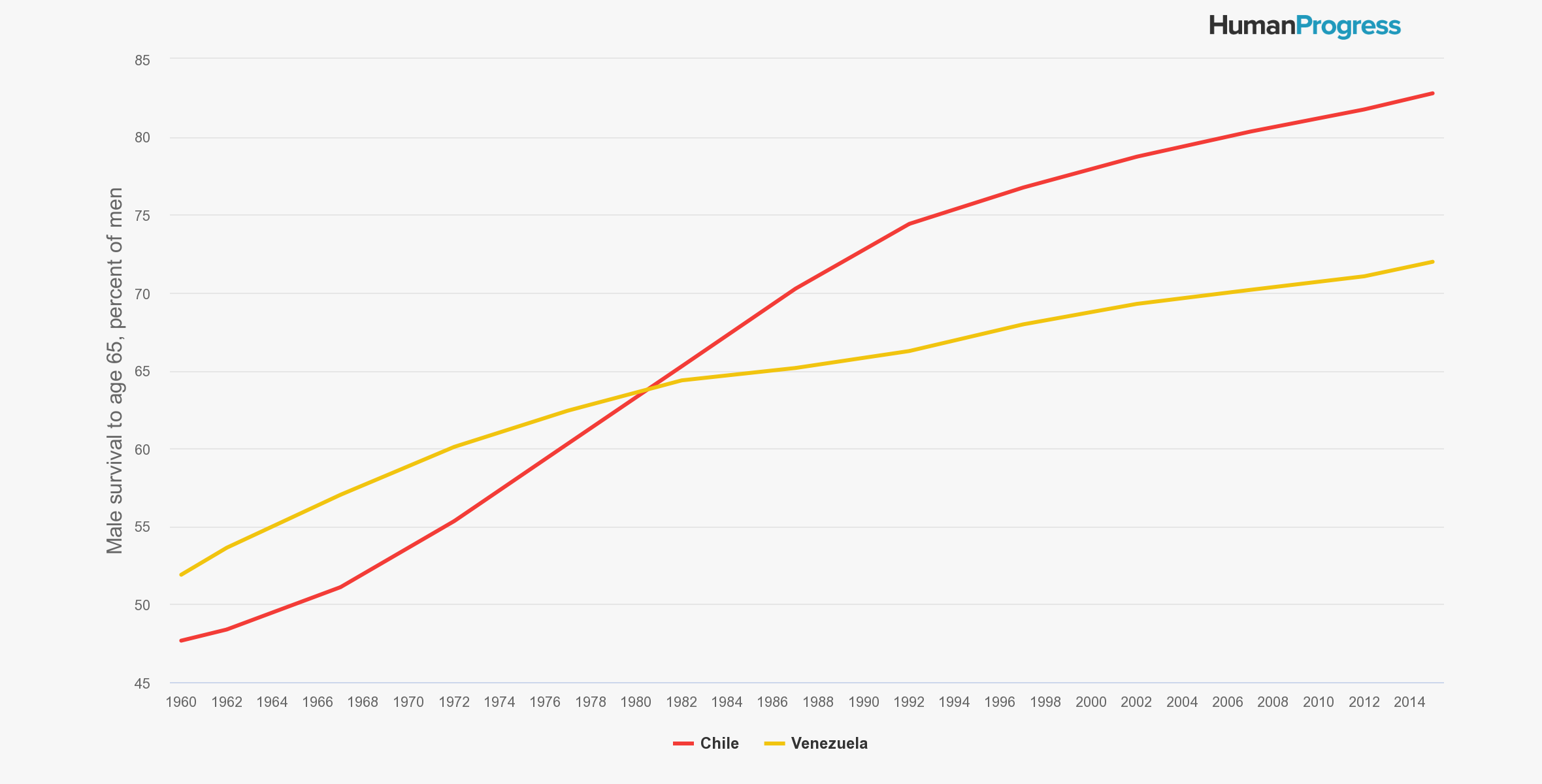

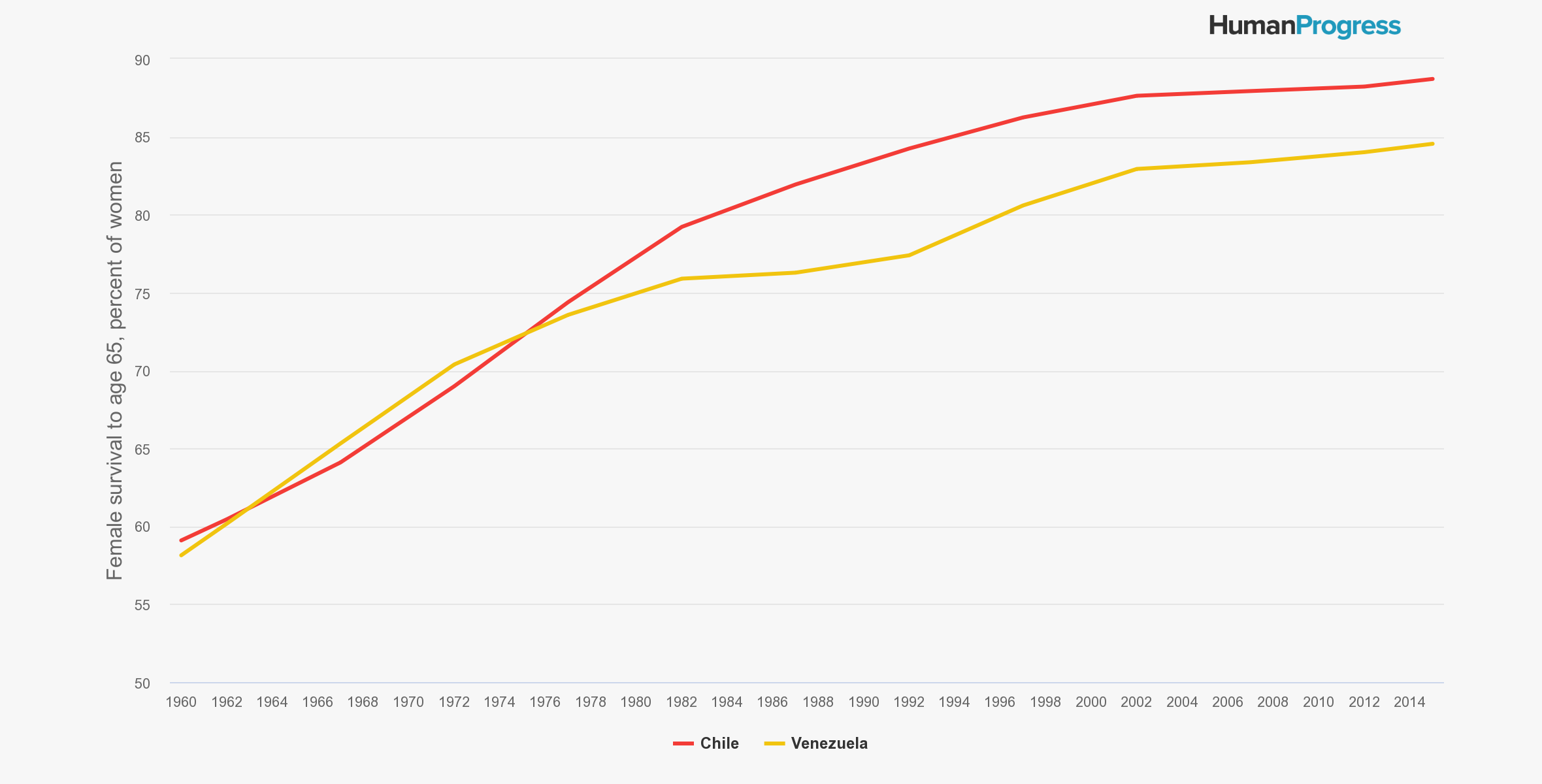

Moreover, more Chileans of both sexes survive to old age than they do in Venezuela. As they enter their retirement, the people of Chile enjoy a private social security system that was put into place by Cato’s distinguished senior fellow José Piñera. The system generates an average return of 10 percent per year (rather than the paltry 2 percent generated by the state-run social security system in the United States).

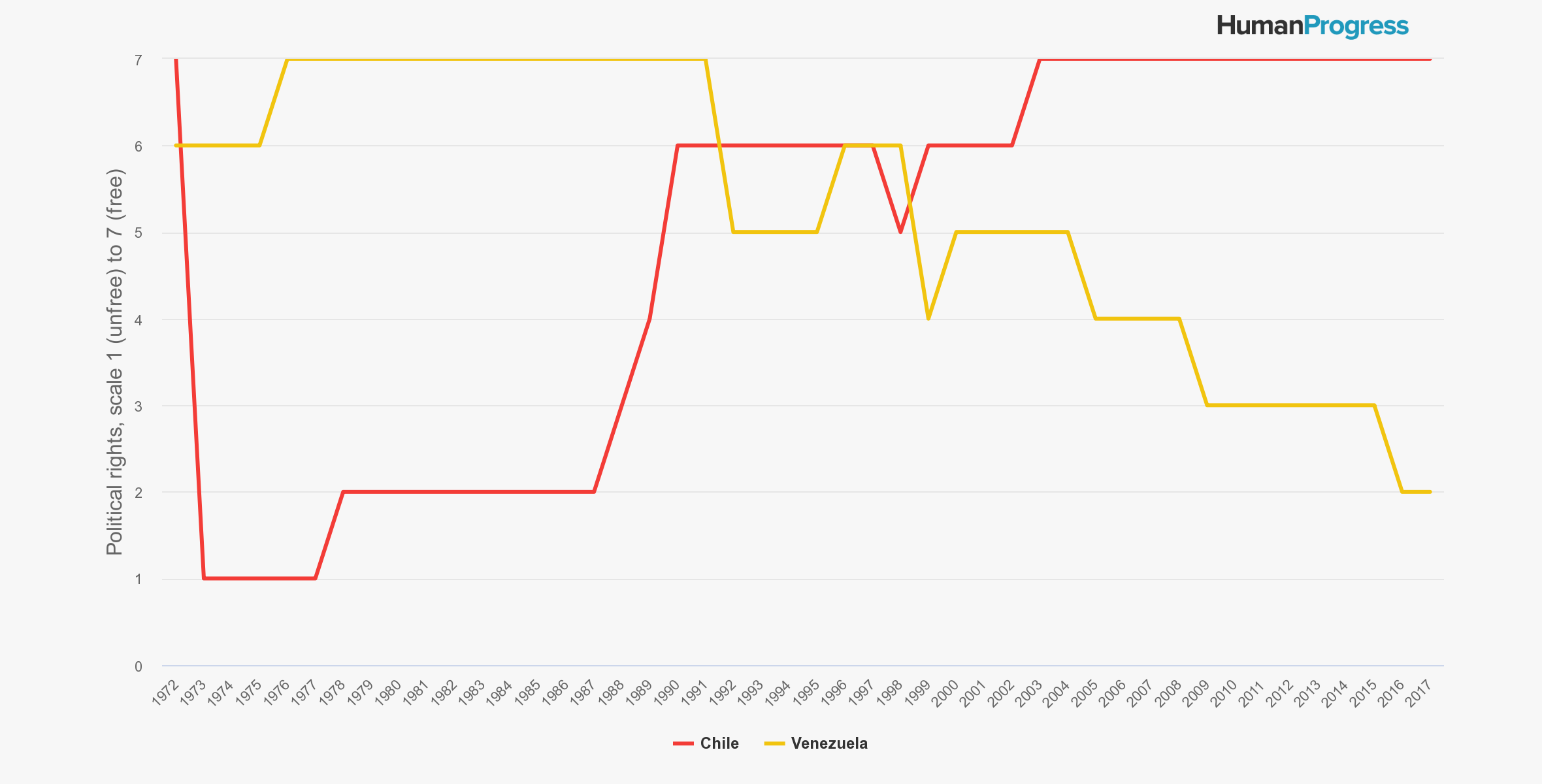

Finally, consider democracy. In his 1944 book The Road to Serfdom, the Austrian-born economist Friedrich Hayek explained that economic interventionism leads to massive inefficiencies and long lines outside of empty shops. A state of economic crisis ensues, leading to calls for yet more economic interventionism.

But increasing state control of the economy is inimical to freedom. First, there can be no agreement on a single economic plan in a free society. As such, centralization of economic decision-making has to be accompanied by the centralization of political power in the hands of a small elite. Second, as the economy deteriorates, authoritarian regimes that are determined to stay in power must silence the dissenters – through incarceration and even murder.

The economic and political deterioration of Venezuela has followed the pattern that Hayek described in 1944. In Chile, in contrast, free markets dispersed economic power amongst millions of Chileans and the military government, which ran the country between 1973 and 1990, gave way to democracy. Today, Chile is both economically and politically free.

This first appeared in CapX.