Summary: Despite widespread fears about the future—from apocalyptic collapse to resource depletion—human history shows a consistent pattern of progress and resilience. Time and again, predictions of disaster have been proven wrong by innovation and adaptation. Though challenges remain, the data clearly show that global living standards are rising—and that fear often lags behind reality.

Fear is one of the oldest and strongest human emotions. From the cradle to the grave, we are constantly afraid of something. For example, many of us fear the end of the world. For centuries, successive apocalypse dates, pointed out by self-proclaimed prophets, passed one by one—I’ve already lived through 30 such dates. Despite those predictions, doomsday fear is still widespread. In some surveys conducted in the West, more than 50 percent of respondents reported fearing the coming apocalypse.

In the 19th century, people commonly feared trains. Not only were they afraid of dying under the wheels of the speeding steel monster, but they were also afraid of the train ride itself. Scientists warned people that train travel was detrimental to one’s health; that one could develop nystagmus from staring at the flashing images outside the window and experience muscle pain from hours of relentless tension generated by traveling at unnaturally high speeds.

Folks also feared electricity. In 1889, for example, after several accidents occurred while men were repairing power line failures, almost all the power lines in New York City—which had been built with great difficulty—were dismantled.

We have also taken steps to abolish nuclear power based on the belief that it is a deadly threat. The 1986 Chernobyl disaster is often cited as irrefutable proof of that. Neither the fact that you can now safely take a tour of Chernobyl and have lunch in the former plant’s canteen, nor the scientific research showing that nuclear power is one of the safest sources of energy, is enough to convince the fearful to change their minds.

Some are still concerned that Earth is overpopulated and lacks sufficient resources for everyone. They heed the predictions of Thomas R. Malthus, an Anglican pastor who, in 1798, argued that unchecked population growth would lead to catastrophic food shortages. Malthus also wrote that the poor, the hungry, and the sick should not be helped, because if they survived and had more children, overpopulation and widespread famine would ensue.

At the same time, the public remains skeptical of the claims of the Danish economist Ester Boserup, who in 1965 claimed that we will never run out of food. In fact, she was right. We have been producing more food for centuries; we have newer and more efficient techniques of land cultivation and agricultural production, and the volume of production follows the demand for food.

Almost from the moment oil production began, we have been concerned that oil supplies would soon run out. Peak oil predictions have been made by American geologists in 1919, by geophysicist M. King Hubbert in 1956, by biologist Paul Ehrlich in 1968, and by environmentalist Donella Meadows in her famous book Limits to Growth in 1972, among others.

Nevertheless, in 2025, we’re producing more oil every year. In 2017, the United States once again became the world leader in oil production, even though oil production in the US was predicted to peak irreversibly as early as 1971.

Survey: Has global poverty increased or decreased over the past 20 years?

The greatest fear of all is the belief that the world is headed in the wrong direction and that the past was better than today. In a 2017 Ipsos international survey, 52 percent of respondents believed the level of poverty in the world had increased over the previous 20 years. Only 20 percent held the opposite, which is to say correct, view. In only one of the nearly 30 countries surveyed—China—did more people believe that the global situation was improving instead of worsening. Yet, no matter what indicators we use to measure the global standard of living, we can easily prove that humanity is living better and better.

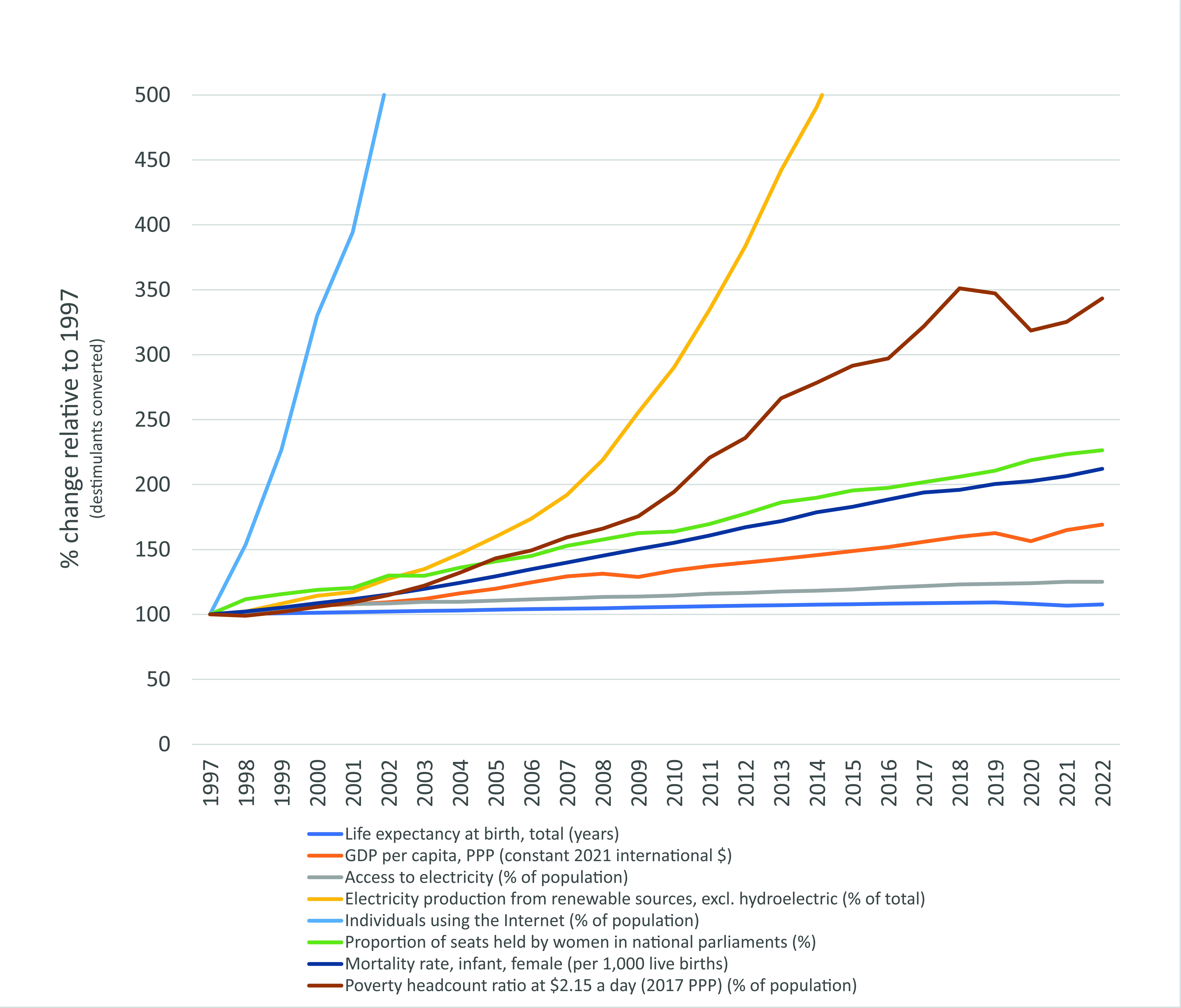

Changes in living standards, 1997–2022

Everything is not perfect. After all, we have wars, terrorists, climate change, and so on. But when I ask any audience: “Who would like to magically move back to the world of a century ago, with no right to return to 2025?” there are no takers.

For more, see Wojciech Janicki’s book Fear/Less: Why Your Lifelong Fears Are Probably Groundless.