Given the most recent political developments in the United Kingdom, including the Supreme Court’s decision on the prorogation of Parliament and the subsequent heated debate in the House of Commons, September 18 feels like a lifetime ago. Yet it was on that date that a rather bizarre incident took place.

Guy Verhofstadt, the Belgian MEP and Brexit coordinator, tweeted that the European Parliament “will never accept the UK can have all the advantage of free trade, and not aligning with our ecological, health & social standards. We are not stupid! We will not kill our own companies, economy, single market. We will never accept ‘Singapore by the North Sea’!”

What exactly is wrong with being Singapore and what does the fear of “Singapore by the North Sea” say about the European Union?

Let’s start with the second question. According to the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World report, the city state has had the world’s second freest economy since 1990. It has a relatively small government (i.e., government spending, taxes and subsidies are by-and-large smaller than elsewhere), independent and reliable legal system that protects private property, sound money (i.e., low inflation), exceptionally open or “free” trade relations with other countries, relatively low regulation of credit and labor markets, and a welcoming business environment. Only Hong Kong’s economy is freer.

As predicted by economic theories going back to Adam Smith’s 1755 observation that “Little else is requisite to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice,” Singapore is very prosperous (more on that below).

Verhofstadt’s admission that an open and, consequently, highly competitive economy (according to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Singapore had the third most competitive economy in the world in 2017) on Europe’s doorstep would damage the EU’s economic interests is damning. It implicitly acknowledges that the EU is less competitive than it could be if it did not over-regulate the single market and more protectionist than it should be in order to compete with the rest of the world.

That leads to the first question. All jurisdictions (be they independent states, like the United States, or international entities, like the EU) have to make a tradeoff between the values they hold dear, such as Verhofstadt’s “ecological, health & social standards,” and international competitiveness. The EU could abolish all industrial emissions, but suffer sky-high energy prices and slower growth rates. It could ban the last trace of carcinogens in foodstuffs, but experience a huge spike in food prices. It could wrap all workers in bubble-wrap, but suffer lower productivity.

Or so we are told … for looking at Singapore a somewhat different picture emerges. The country, so it seems, was able to combine high growth and income with decent “ecological, health & social standards.” Let’s look at the data.

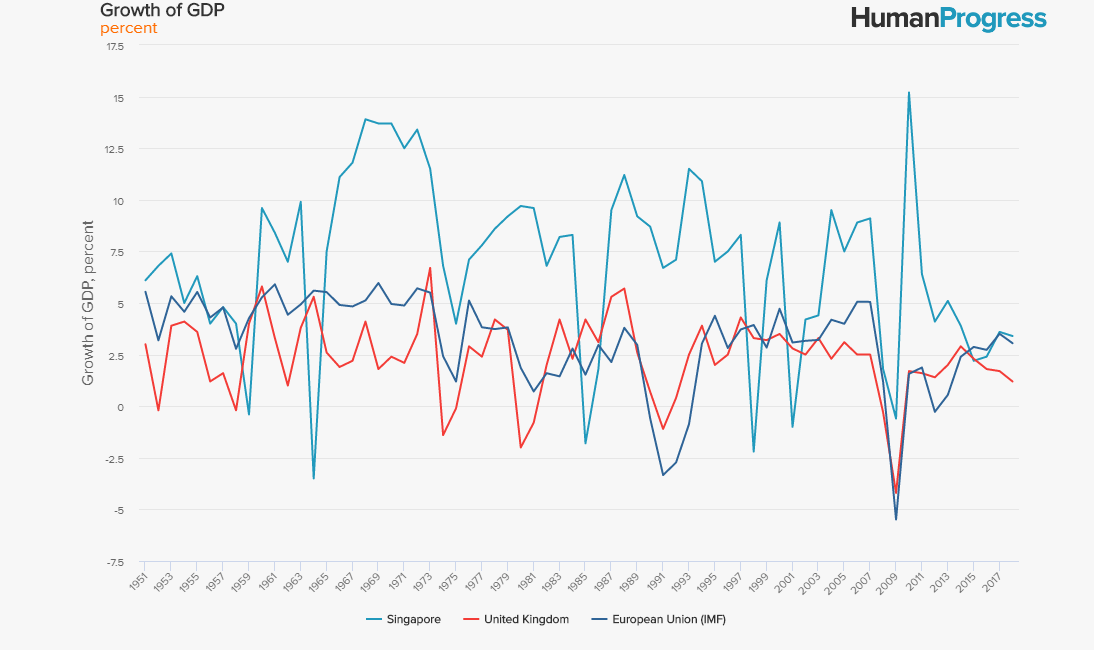

1. GDP growth, percent (1951-2018)

As can be seen, the economy of Singapore grew at a faster pace than that of the UK and the EU, in spite of the latter’s data being boosted by fast growing economies of ex-communist countries.

2. GDP growth per capita, 2018 U.S. dollars (1950-2019)

As can be seen, Singapore’s GDP per capita, which amounted to 72 percent of the EU’s GDP per capita in 1950, amounted to 219 percent of the EU’s GDP per capita in 2019. Relative to the UK, Singapore’s GDP per capita rose from 50 percent to 208 percent over the same time period.

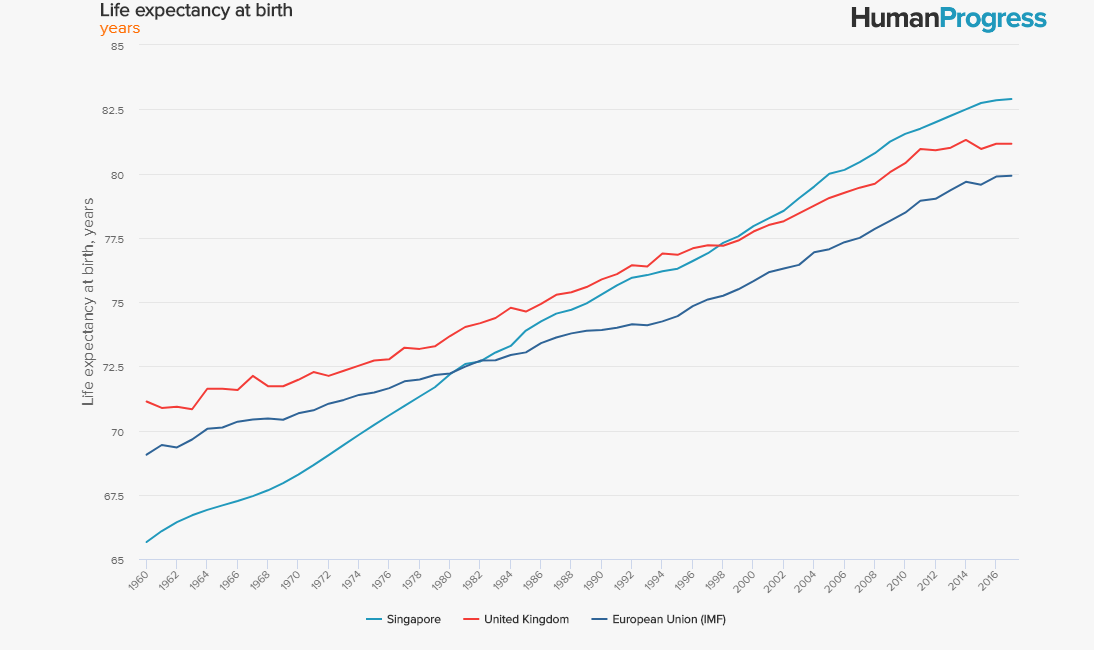

3. Life expectancy at birth, years (1960-2017)

Life expectancy at birth is the best proximate measure of the overall health of the population. As can be seen, life expectancy in Singapore trailed the EU and UK in 1960. In 2017, Singaporeans lived, on average, longer than Europeans.

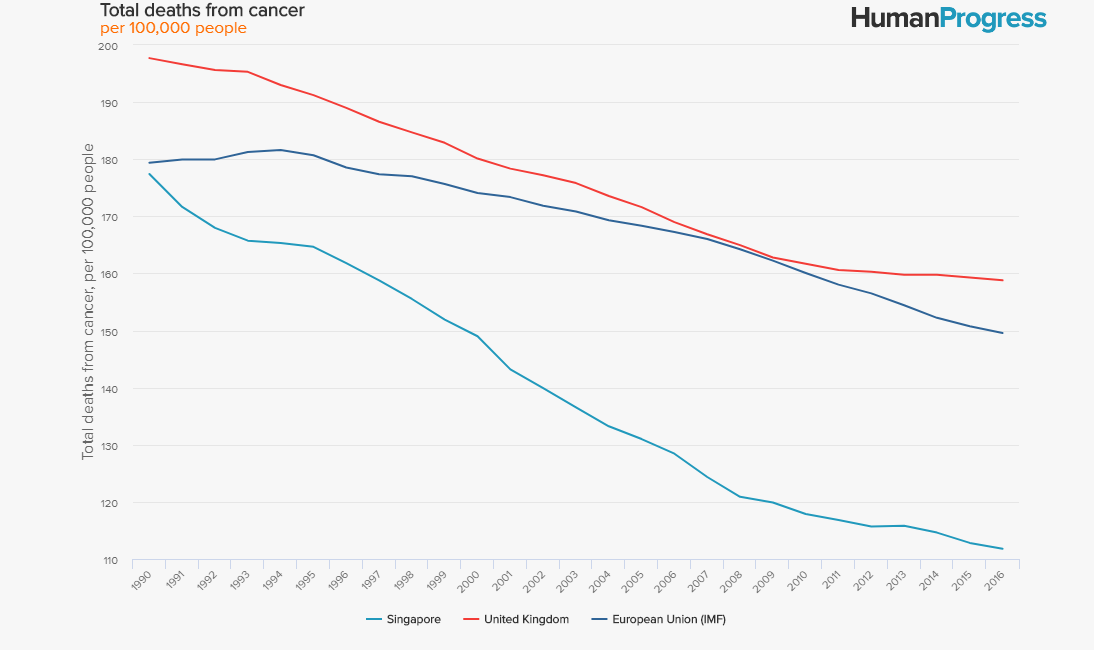

4. Total deaths from cancer, per 100,000 people (1990-2016)

Part of the reason for Singapore’s impressive gains in life expectancy is due to plummeting cancer death rate, which was roughly equivalent to that of the EU in 1990, but was one fourth lower in 2016.

On other social indicators, Singapore’s record is mixed, but a far cry from the dystopian nightmares of Guy Verhofstadt’s fevered dreams.

According to the International Labour Organization, 2.8 workers per 100,000 died on the job in 2008 (the last year for which ILO has data for the city state). In the UK, it was 0.8 deaths (2015), Germany 1 death (2015), Belgium 1.6 deaths (2015) and France 2.6 deaths (2015). So, Singapore’s work safety record is not exactly stellar, but also not very different from the notoriously over-regulated labor market in France.

What about the quality of the environment? According to the Environmental Performance Index that is produced by the Yale Center for Environmental Law and Policy, Singapore ranked 49th out of the 180 countries surveyed. The UK, Germany, France and Belgium ranked 6th, 13th, 2nd and 15th respectively. So, once again, Singapore does not meet the highest environmental standards. That being said, Singapore scored well compared to a number of EU countries, including Croatia (41), Hungary (43), Poland (50) and Romania (45).

Perhaps surprisingly, given that space is extremely valuable in a tiny country like Singapore, the city state does surprisingly well when it comes to tree coverage. In 2015, the percent of land area covered by forests in Singapore (23 percent) was lower than the EU average (34 percent), but higher than UK’s 13 percent.

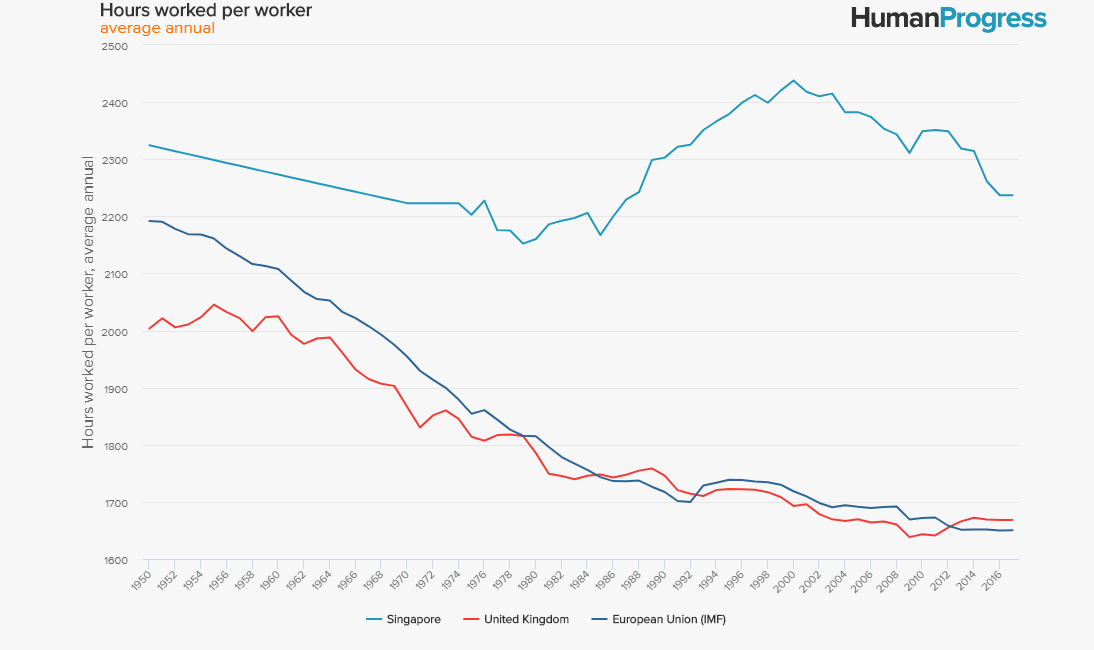

Finally, let us look at income inequality and working time. According to Branko Milanovic, an authority on income inequality, Singapore scored 48 on a scale from zero (i.e., a country where people earn exactly the same amount of money) and 100 (i.e., a country where one person earns all the income produced) in 2012. That put the city state on par with the United States, but far above the EU (32) and the UK (36). In addition, Singaporeans work many more hours per year than Europeans do.

So, what are we to make of Singapore? Singaporeans live longer and healthier lives than Europeans do. They are, also, much richer. Environmental protection is not as high as that in Western Europe, but it is comparable to a number of Central and Eastern European EU member states. To the extent that the people of Singapore “pay a price” for their prosperity it is in long working hours and relatively high income inequality. Is that a price worth paying? That’s the question that the people of the United Kingdom will have to answer for themselves as they chart the course of post-Brexit independence.

A version of this article first appeared in CapX.