Today marks the ninth installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org called Centers of Progress. Where does progress happen? The story of civilization is, in many ways, the story of the city. It is the city that has helped to create and define the modern world. This bi-weekly column will give a short overview of urban centers that were the sites of pivotal advances in culture, economics, politics, technology, etc.

Our ninth Center of Progress is ancient Rome during its Republican and early Imperial periods, when the Romans built infrastructure projects that were, at the time, unparalleled in their sophistication. Those projects ranged from aqueducts and sewers to bridges, amphitheaters, and bathhouses. The viae Romanae (“Roman ways”) or Roman road network, in particular, represented a breakthrough. While built in part to ease the transportation of soldiers and the delivery of military supplies, the roads greatly aided the free movement of civilians and trade goods. The Romans pioneered new concepts such as milestone markers, advanced surveying, and various engineering marvels, such as viaducts, to generate the shortest and straightest possible routes.

While the Romans did not invent roads—a Bronze-Age innovation—the Romans vastly improved upon roads’ concept and potential. As early as 4000 BC, the older Indus Valley Civilization created paved and straight roads intersecting one another at right angles. But the sheer scale of the later Roman road network and the institution of several important innovations would forever alter the way people travel.

Today, we take advanced road systems for granted, but reliable roads were once a rarity, and many journeys, of course, took place with no roads at all. By making travel faster and easier, Roman roads greatly increased the efficiency of transporting trade goods, people, and messages. The Roman road system increased the rate of cultural exchange and encouraged connections that helped to unify the Roman Empire—a melting pot of different cultures, beliefs, and institutions.

Major roadways within the Roman road system were typically paved with stone and flanked by bridleways or horse trails and footpaths to separate different kinds of traffic. The roads were also often cambered to allow rainwater to drain into parallel drain ditches or gutters. At the peak of Rome’s strength and influence, the Empire’s provinces were interconnected by 372 great roads, and no fewer than 29 major highways radiated from the city of Rome itself. Thus the popular expression, “All roads lead to Rome.”

Today, Rome is the capital city of Italy and the country’s most popular city for tourism. It is also a major European business center and the seat of several United Nations agencies. It is additionally home to the Pope, also known as the Bishop of Rome, who is the head of the Catholic Church. Located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, Rome is among the oldest continuously occupied cities in Europe. Many historians consider it to be the world’s first-ever Imperial City and true metropolis. Rome’s nicknames include The Eternal City (“Urbs Aeterna” in Latin; “La Città Eterna” in modern Italian) and “Caput Mundi” (Latin for The Capital of the World).

Tradition holds that Rome was founded in 753 BC, although the area was likely inhabited beforehand. According to legend, the sister of the ruler of Alba Longa, a Latin city in Central Italy, gave birth to twin boys who were ostensibly fathered by Mars, the Roman god of war. The ruler saw the newborns as a threat to his rule and forced his sister to abandon them. The twin brothers, Romulus and Remus, were then allegedly nursed by a female wolf and adopted by a shepherd. They grew up to lead a successful rebellion against their uncle and reinstate their grandfather as king. After doing so, they returned to the hills (i.e., the famed Seven Hills of Rome), where they decided to build a city. A disagreement about the precise location of the city (Romulus is said to have preferred the Palatine Hill and Remus is said to have preferred the Aventine Hill) led Romulus to kill his brother. After founding Rome, Romulus reigned over it as its first king.

Ancient Roman history is typically divided into three eras based on the city’s evolving governing structure: the Period of Kings (625–510 BC), Republican Rome (510–31 BC), and Imperial Rome (31 BC–476 AD). In keeping with the myth of being founded by a son of the god of war, throughout much of its history, Rome was in a state of conflict. It served as the capital city of a polity that often sought to expand its territory. At its peak, the Roman Empire encompassed an area of almost 2 million square miles. It contained modern-day Spain, Portugal, France, Belgium, parts of Germany, England, Wales, much of Central and Southeast Europe, Turkey, parts of Syria, and lengthy territory along the coast of northern Africa, including a substantial portion of Egypt.

To support their expansionism, the Romans eventually formed a large, elite professional army. Motivated in part by the need to move their soldiers across vast distances, the Romans created their extensive road network, the remnants of which are still visible across much of Europe and parts of North Africa and the Middle East. Not until the Incan Empire’s road network, a thousand years later, would a comparably complex road system arise. (The Roman network was twice as many miles long as the Incas’ road system).

The first major road constructed by the Romans was the Appian Way, which connected the city of Rome with Capua, on the northeastern edge of the Campanian plain. Construction of the Appian Way began in 312 BC, during the Republican period when Rome was governed by an unelected senate and officials called consuls. (It should be noted that the city’s republican system was oligarchical, with a few wealthy families maintaining most of the power, and not a democracy).

By around 244 BC, the road was extended to stretch past Capua to Brindisi, a port city on the Adriatic Sea, located in southeastern Italy’s Apulia region. The Appian Way’s praises were sung by the poets Horace and Statius, who called it longarum regina viarum, or “queen of long-distance roads.” As the best route to the seaports of southeastern Italy, and thus an important gateway to Greece and the eastern Mediterranean, the Appian Way was of tremendous strategic importance.

While the Appian Way was first built to speed the delivery of military supplies during the Samnite Wars, it proved to be the first in a series of highways with an importance that went far beyond military uses. If you could visit Rome a few centuries later, during the era of Augustus Caesar—the grand-nephew and adopted son of Julius Caesar, who made an appearance in our last Centers of Progress installment—when the road network was already well-established, you would have entered the thriving capital city of a far-reaching empire connected by the viae Romanae.

Augustus took advantage of growing cynicism towards the Republic, which came to be widely viewed as corrupt, to seize absolute power. He pretended that he was not a king, taking the title “First Citizen” instead. Augustus bought the public’s support through the expansion of the Roman welfare system—which would eventually reach unsustainable levels. He also instituted a series of (to the modern eye) bizarre, sexist, and draconian morality laws known as the Leges Iuliae, which legalized the murder of alleged adulterers in many cases and pressured widows to remarry. The laws were poorly received and short-lived.

However, Augustus’s reign also saw the beginning of an era of relative peace known as the Pax Romana, in which Rome avoided entanglement in a major war for almost two centuries, although it continued small-scale wars of expansion. Benefiting from this relative peace, as well as an exceptional trade network aided by the Roman Empire’s roadways, the city of Rome grew and prospered. As a visitor, you would have been mesmerized by the imposing architecture of its massive buildings and bustling crowds of diverse people moving through its streets, typically clad in tunics. Men wore knee-length tunics called chitons and, sometimes, togas. Women wore ankle-length tunics and, sometimes, woolen stolae, like the one that the Statue of Liberty wears tied at her shoulder.

Like all ancient civilizations, Romans practiced slavery, and many people, even in skilled positions, such as accountants and physicians, were enslaved. A modern person would also be horrified by the degree of poverty in the city. But for its era, Rome was among the wealthiest places on Earth. The city of Rome itself held around 1 million inhabitants at the time or was at least fast-approaching that number. That constituted an urban population not equaled again in any European city until the 19th century. While that is around the same size as the population of today’s San Jose, California, it was then a metropolis of unrivaled magnitude.

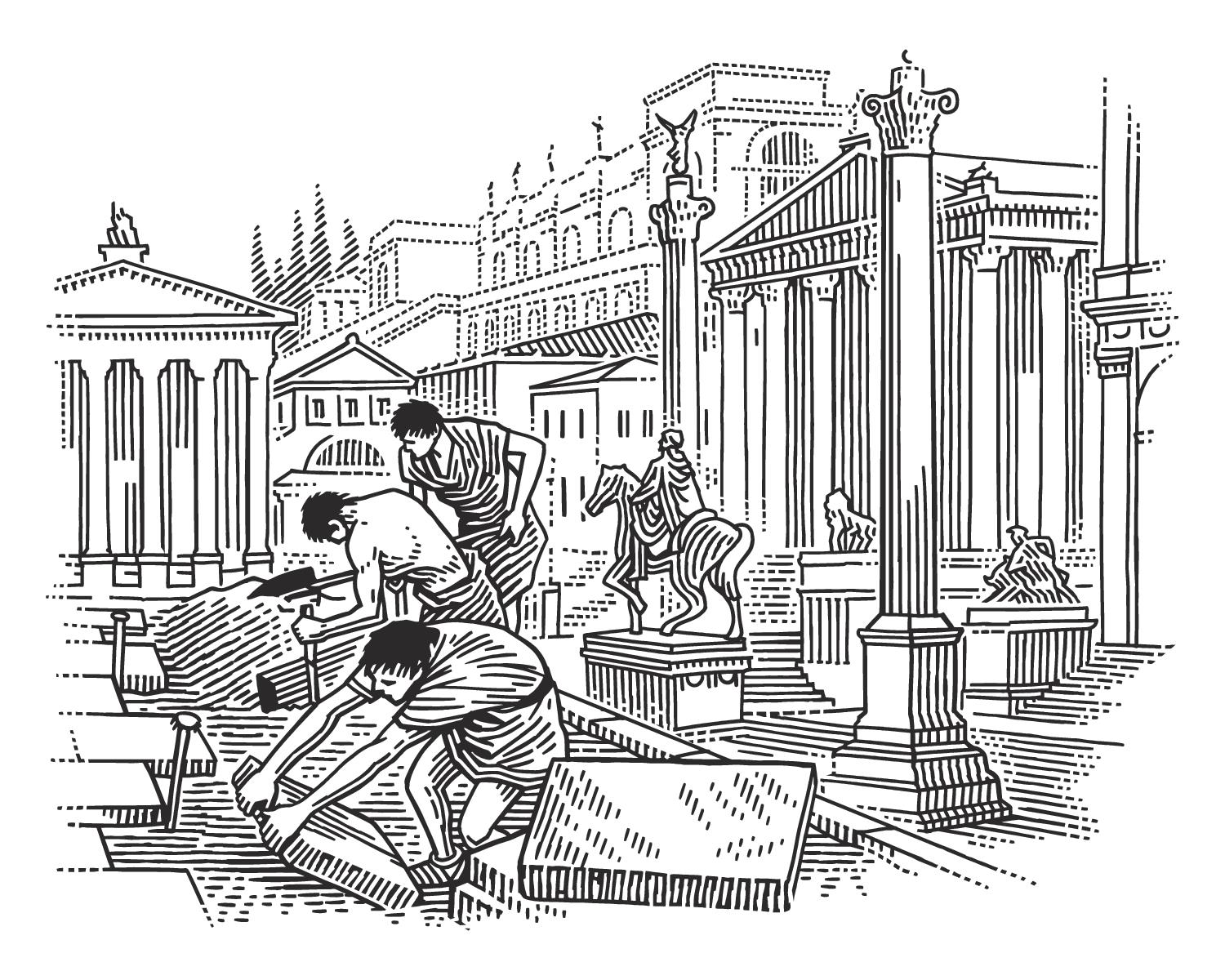

At the center of the city was the Roman Forum, a rectangular travertine-paved plaza flanked by several significant buildings. Romans referred to this space as the Forum Magnum, or simply as “the Forum.” Originally the city’s marketplace, the Forum became the city’s civic center during the Republican era. It was home to public meetings, law court sessions, and gladiatorial fights, and remained lined with shops that formed an open-air marketplace. In the period that concerns us, the Forum’s primary role was beginning to shift to serve as a center for religious and secular spectacles and ceremonies. It was also the endpoint of celebratory military parades or processions known as Triumphs.

Entering the Forum in 20 BC, you might have witnessed the erection of the Milliarium Aureum or Golden Milestone. The Golden Milestone was an important monument, likely measuring about 12 feet high and constructed of marble that was possibly sheathed in gilded bronze. It stood near the prominent Temple of Saturn in the bustling central Forum. The monument was the symbolic and practical midpoint of the Roman road system. All roads were considered to begin at the Golden Milestone, and all distances in the Roman Empire were measured relative to the monument. To this day, a marble structure thought to be the base of the monument can be viewed in Rome.

The monument’s dedication ceremony would have been an exciting affair, perhaps involving festivities, lofty speeches, and a large crowd. The Golden Milestone represented the achievement of connecting much of the world through a network of reliable roads—enabling travel, transportation of goods, and faster delivery of messages.

While most roads were winding and uneven and built to accommodate natural obstacles, the Romans prided themselves on creating straight roads. Instead of having their roads wind around natural obstacles, Roman engineers found ways to continue straight ahead by building bridges, tunnels, or viaducts. They would also drain marshes, cut through forests, or divert the paths of creeks when needed.

Before a road was built, extensive surveying was carried out to find the shortest and straightest possible route between two points and determine what engineering feats would be needed to tackle any obstacles in the way. A surveyor ensured that the land was level and a suggested path marked out with wooden stakes. He would have utilized a tool called a groma (a wooden cross with weights), to make certain that the lines were straight. Once the path was decided upon, the Romans would create earthen banks called aggers upon which they would lay the road material, and dig a ditch on either side for drainage.

Roads were sometimes built of several layers, with stone blocks overlying crushed stone or gravel in cement atop stone slabs (also in cement) above crushed rock over a base layer of compacted sand or dry Earth. These layers gave Roman roads their longevity. While other roads quickly wore down into sunken muddy trails, Roman roads lasted for centuries or even millennia. The Romans also instituted a system of regular milestone markers and standardized road widths. Moreover, they experimented with grooved roads to assist with the transport of wheeled carts and chariots.

Rome remains best-known for its historical influence, including its far-reaching Empire and its fervent rejection of monarchy during the Republican era. The latter would later help to inspire the Founding Fathers of the United States of America. Roman infrastructure projects from the days of the Empire left a permanent mark on the world that’s rather wryly summed up by a scene in a classic British comedy film in which a gathering of people plotting a rebellion against the Romans nonetheless concede that the Romans created great aqueducts, roads, etc.

There are still Roman baths in use in Algeria, two millennia after being constructed, and a Roman amphitheater in France, the Arena of Nîmes, still holds live concerts today. In Rome itself, a section of the Cloaca Maxima (the “Greatest Sewer”), dating to the Augustan period, is still in use. But it was Roman roads that arguably left the greatest mark of all. To this day, many of the roads survive, and some of their alignments are still in use—with modern roads overlaying the original routes. For example, parts of Great Britain’s road system run along old Roman routes—such as much of the 18 miles of the section of the A1 road that links Dishforth and Catterick. While it is no longer true that “all roads lead to Rome,” as the saying goes, many do.

For taking the concept of a road to new heights, creating the greatest road network of the ancient world, and proving the possibility of such a comprehensive, efficient and lasting road system, Rome is rightfully our ninth Center of Progress. Numerous Roman paths, in areas ranging from Western Europe to North Africa, are still traveled today. Rome showed the world the potential of roads to increase the efficiency of travel and the transportation of goods and the delivery of information.