Today marks the twenty-sixth installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org called Centers of Progress. Where does progress happen? The story of civilization is in many ways the story of the city. It is the city that has helped to create and define the modern world. This bi-weekly column will give a short overview of urban centers that were the sites of pivotal advances in culture, economics, politics, technology, etc.

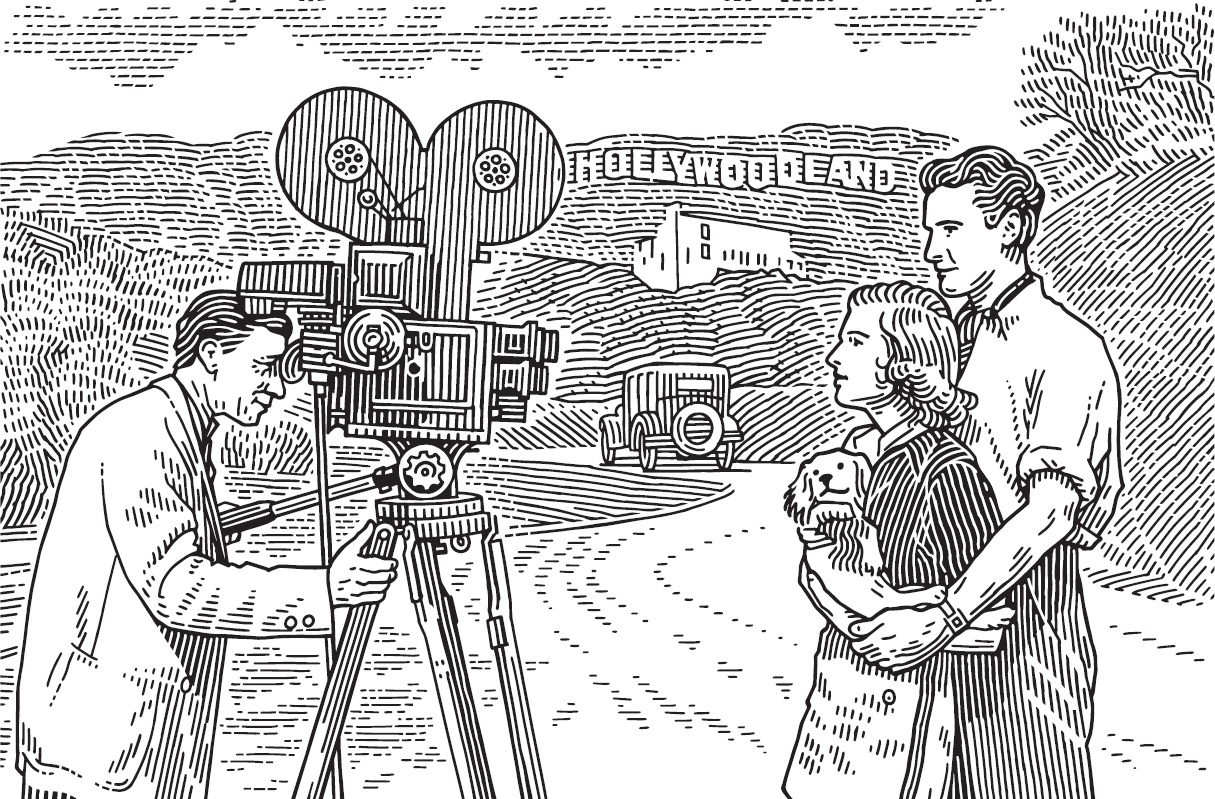

Our twenty-sixth Center of Progress is Los Angeles during the Golden Age of Hollywood (1910s–1960s). The city pioneered new filmmaking styles that were soon adopted globally, giving the world some of its most iconic and beloved films in the process. Los Angeles’s Hollywood neighborhood is synonymous with filmmaking, representing the city’s unparalleled cinematic contributions.

With some four million inhabitants, Los Angeles is only the second most populous city in the United States. However, it may well be the most glamorous, with many celebrities and movie stars calling Los Angeles home. The city is also known for its impressive sports centers and music venues, shopping and nightlife, pleasant Mediterranean climate, terrible traffic, beautiful beaches, and easy-going atmosphere. Two famous landmarks include Disneyland and Universal Studios Hollywood, film-related theme parks that attract around 18 million and 9 million annual visitors, respectively.

The site where Los Angeles now stands was first inhabited by native tribes, including the Chumash and Tongva. The first European explorer to discover the area was Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, who arrived in 1542. Los Angeles’s Cabrillo Beach still bears his name. Spanish settlers founded a small ranching community at the site in 1781, calling it El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles, meaning “the Town of Our Lady the Queen of the Angels.” The name was soon shortened to Pueblo de los Ángeles.

The Mexican War of Independence transferred control of the town from Spain to Mexico in 1821. Then, after the conclusion of the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), the future state of California was ceded to the United States.

That same year, gold was discovered in California. Hopeful miners poured into the area, and when California gained statehood in 1850, the migration intensified. True to its ranching roots, Los Angeles soon boasted the largest cattle herds in the state. The town gained a reputation as the “Queen of the Cow Counties” for supplying beef and dairy products to feed the growing population of gold-miners in the north.

While most of Los Angeles County was cattle ranchland, there were also a number of farms devoted to growing vegetables and citrus fruits. (To this day, the Los Angeles area remains a top producer of the nation’s broccoli, spinach, tomatoes, and avocados). As the local food industry prospered, the city proper began to grow, from around sixteen hundred inhabitants in 1850 to almost six thousand people by 1870.

In 1883, a politician and real estate developer named Harvey Wilcox and Daeida, his significantly younger second wife, moved to town. The pair wanted to try their hand at ranching and bought over a hundred acres of apricot and fig groves. When their ranch failed, they used the land to build a community of upscale homes. They named the new subdivision “Hollywood.”

One story claims that Daeida was inspired by an estate with the same name in Illinois or by a town of the same name in Ohio. Others theorize that the Wilcoxes drew inspiration from a native shrub with red berries called toyon, or “California holly,” which grows abundantly in the area. In tribute to that theory, the Los Angeles City Council named toyon the city’s “official native plant” in 2012. While the true origin of the name “Hollywood” remains disputed, Daeida has been nicknamed the “mother of Hollywood” for her role in the story. (Ironically, she envisioned Hollywood as a Christian “temperance community” free of alcohol, gambling, and the like).

In any case, Hollywood started as a small but wealthy enclave that by 1900 boasted a post office, a hotel, a livery stable, and even a streetcar. A banker and real estate magnate named H.J. Whitley moved into the subdivision in 1902. He further developed the area, building more luxury homes and bringing electricity, gas, and telephone lines to town. He has been nicknamed the “father of Hollywood.”

Hollywood was officially incorporated in 1903. Unable to independently handle its sewage and water needs, Hollywood merged with the city of Los Angeles in 1910. By then, Los Angeles had around 300,000 people. That would top a million by 1930, and by 1960, that would grow to 2.5 million.

The city’s explosive growth can be traced to one industry.

The first film to be completed in Hollywood was The Count of Monte Cristo in 1908. The medium of film was still young, and The Count of Monte Cristo was one of the first films to convey a fictional narrative. Filming began in our previous Center of Progress Chicago, but by wrapping up production in Los Angeles, the film crew made history. Two years later came the first film produced start-to-finish in Hollywood, called In Old California. The first Los Angeles film studio appeared on Sunset Boulevard in 1911. Others followed suit, and what began as a trickle soon turned into a flood.

What led so many filmmakers to relocate to Los Angeles? The climate allowed outdoor filming year-round, the terrain was varied enough to provide a multitude of settings, the land and labor were cheap—and, most importantly, it was far away from the state of New Jersey, where the prolific inventor Thomas Edison lived.

With exclusive control of many of the technologies needed to make films and operate movie theaters, Edison’s Motion Picture Patent Company had secured a near-monopoly on the industry. Edison held over a thousand different patents and was notoriously litigious. Moreover, Edison’s company was infamous for employing mobsters to extort and punish those who violated his film-related patents.

California was the perfect place to flee from Edison’s wrath. Not only was it far from the East-Coast mafia, but many California judges were hesitant to enforce Edison’s intellectual property claims.

The Supreme Court eventually weighed in, ruling in 1915 that Edison’s company had engaged in illegal anti-competitive behavior that was strangling the film industry. But by then, and certainly by the time that Edison’s film-related patents had all expired, the cinema industry was already firmly planted in California. Edison has been called “the unintentional founder of Hollywood” for his role in driving the country’s filmmakers to the West coast.

Hollywood became the world leader in narrative silent films and continued to lead after the commercialization of “talkies,” or films with sound, in the mid-to-late 1920s. At first, such films were exclusively shorts. Then, in 1927, Hollywood produced The Jazz Singer, the first feature-length movie to include the actors’ voices. It was a hit. More and more aspiring actors and film producers flocked to Los Angeles to join the burgeoning industry.

In the 1930s, Los Angeles studios competed to wow audiences with innovative films. The Academy Awards, or Oscars, were first presented at a private dinner in a Los Angeles hotel in 1929 and first broadcast via radio in 1930. They remain the most prestigious awards in the entertainment industry to this day. Distinct movie genres soon emerged, including romantic comedies (including the beloved film It Happened One Night, which swept the Oscars and boasts a near-perfect score on Rotten Tomatoes), musicals, westerns, and horror films, among others.

The innovations of that era continue to influence movies today. King Kong premiered in 1933. In 2021, its namesake giant ape appeared in his twelfth feature film, this time battling Godzilla. Hollywood gave the world its first full-length animated feature film in 1937 with Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. In 1939, Hollywood popularized color productions with the release of The Wizard of Oz. While it was not the first color film, it was among the most influential in promoting the technology’s widespread adoption.

In the 1940s, the iconic “Hollywood sign” first appeared in its current incarnation, replacing a sign reading Hollywoodland erected in 1923. The next few decades saw the production of some of history’s best-loved classic films. Those include Citizen Kane (1941), Casablanca (1942), It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), Singin’ in the Rain (1952), Rear Window (1954), 12 Angry Men (1957), Vertigo (1952), Psycho (1960), Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966). Many remain top-rated productions, beating decades of more recent movies to appear in the Internet Movie Database’s top 100 films sorted by user rating.

As it transformed from a humble cattle town into the geographic center of filmmaking, Los Angeles came to define a new art form. Movies enrich humanity by providing entertainment, inspiration, laughter, and thrills. Moreover, films create cultural experiences that can bring people together, act as an artistic outlet, and even shift worldviews. Hollywood created modern cinema. Thus, every person who has ever enjoyed a movie, even one produced elsewhere, owes a debt of gratitude to Los Angeles. It is for those reasons that Los Angeles is our 26th Center of Progress.