Today marks the twenty-fifth installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org called Centers of Progress. Where does progress happen? The story of civilization is in many ways the story of the city. It is the city that has helped to create and define the modern world. This bi-weekly column will give a short overview of urban centers that were the sites of pivotal advances in culture, economics, politics, technology, etc.

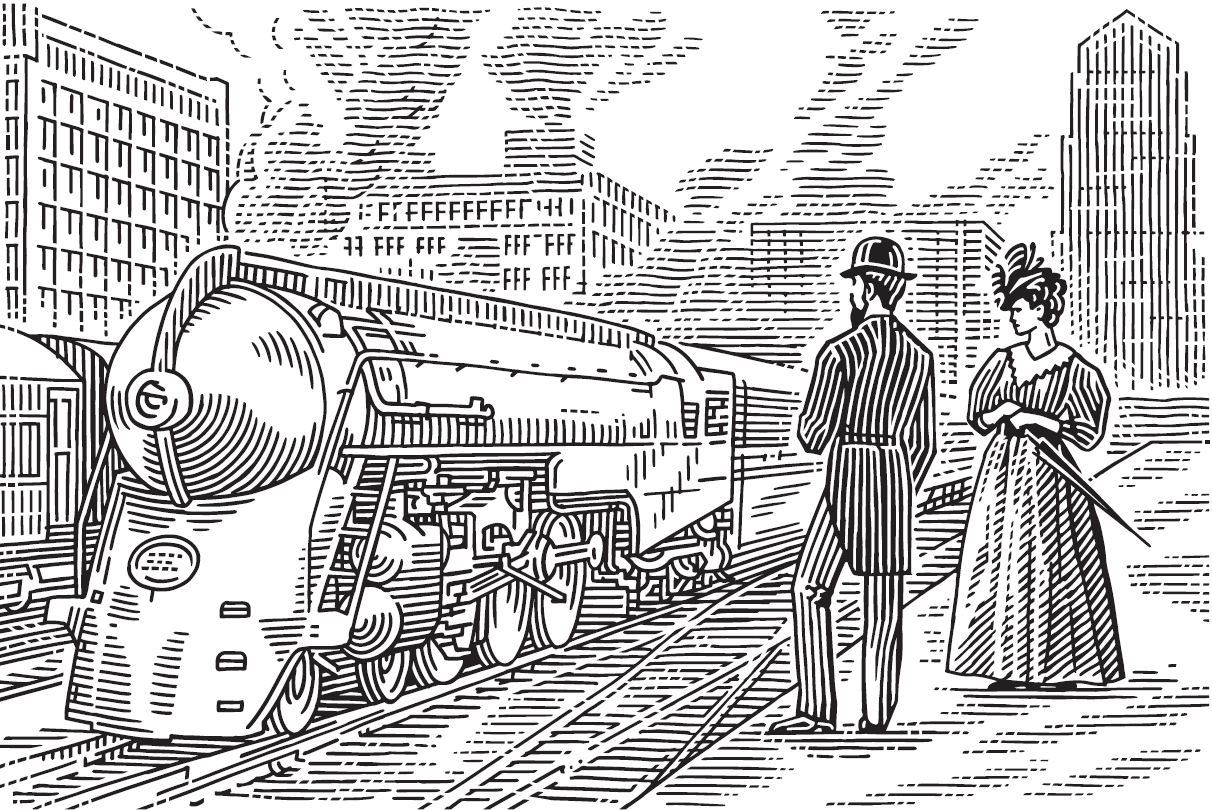

Our twenty-fifth Center of Progress is Chicago during the Age of Steam. Chicago played a central role in the popularization of rail transportation and is the most important railroad center in North America today.

With around 2.7 million inhabitants, Chicago is the third most populous city in the United States. It is a major hub of commerce, boasting a diverse economy. As the city that erected the first modern skyscraper in 1885, Chicago is well-known for its distinctive buildings and other contributions to architecture. For example, the so-called Windy City is home to the 1,450-foot-tall Willis Tower, previously called the Sears Tower. That structure was the tallest building in the world for almost a quarter century. It is still the third-tallest building in the United States, and its observation deck now serves as a tourist attraction.

The city is also famous for its music, food (such as the city’s signature deep-dish pizza), arts scene, sports (particularly the storied Chicago Cubs baseball team), and research universities. Those include Northwestern University and the University of Chicago. The latter gave the world the influential Chicago school of economics. Chicago is a cultural mixing bowl with large Italian-, Polish- and Irish-American populations, among others. Every year, during the St. Patrick’s Day celebration, which honors the patron saint of Ireland, the Chicago River that flows through the city is dyed green.

Even putting railroads aside, Chicago is an important transportation center. The city’s O’Hare International Airport ranks as the sixth busiest in the world and the third busiest in the country. And the area surrounding Chicago has the largest number of federal highways in the United States.

The site where Chicago now stands was first inhabited by various native tribes. Chicago’s attractive location between the Great Lakes and navigable Mississippi River waterways made it a transportation center even then. The first non-native settlers of the area spoke French. The name “Chicago” comes from the French pronunciation of a word used by the local indigenous people for a kind of wild garlic that grew abundantly in the area. (In fact, the vegetable still abounds and can be found in many Chicago restaurant dishes and artisan grocery stores).

The first non-indigenous Chicagoan was Jean Baptiste Point du Sable (before 1750–1818), a frontiersman of African descent who married a native woman and settled in the area. He made a living as a trader and is widely considered to be “Chicago’s founder.” Point du Sable’s business flourished and made him into a wealthy man. The small settlement he began at the mouth of the Chicago River would one day help to enrich humanity.

Chicago was rural at first. The town was officially incorporated in 1833 with a modest population of just 350 residents. However, the settlement was surrounded by rich farmland and well-situated to transport food by boat throughout the Great Lakes region. As early as the 1830s, entrepreneurs saw Chicago’s potential as a transportation hub and began buying land in a flurry of speculation. By 1840, the little “boom town” boasted four thousand inhabitants. By 1850 it had almost thirty thousand people.

Then the trains started arriving, and the city was never the same. Chicago’s inaugural railroad was the Galena and Chicago Union. It welcomed its first locomotive, “The Pioneer,” on October 10, 1848. Nearly overnight, the city became a major commercial center. In 1852, one Chicagoan asked, “Can it be wondered at, that our city doubles its population within three years; that men who were trading in small seven-by-nine tenements, now find splendid brick or marble stores scarcely large enough to accommodate their customers?”

A stunned British visitor to Chicago during the 1850s wrote, “The growth of this city is one of the most amazing things in the history of modern civilization.” He referred to Chicago as “the lightning city.” Starting in 1857, durable steel rails—still the standard around the globe—replaced cast-iron rails. That innovation allowed trains to move twice as fast as before, greatly improving trains’ practicality and further boosting steam transportation.

Chicago’s rapidly rising population brought new public health challenges. An insufficient waste-drainage system allowed pathogens to infect the water supply and caused outbreaks of illnesses such as typhoid and dysentery. One 1854 bout of cholera killed six percent of the city’s population. Recognizing the problem, private property owners and city leaders cooperated to improve the city’s drainage system in the late 1850s and 1860s. To make room for new sewers, they lifted the city fourteen feet in a Herculean feat of engineering. The “Raising of Chicago,” as the endeavor came to be known, was accomplished piecemeal by lifting the city’s massive brick buildings, streets, and sidewalks using large jackscrews operated by hundreds of men. If that is difficult to imagine, here is a visual. It was perhaps the most striking event of the modern sanitation movement that Nobel Prize-winning economist Angus Deaton partly credits with the dramatic rise in human life expectancy.

By 1870, Chicago’s population had grown to almost 300,000 souls. Then tragedy struck. On a series of dry October days in 1871, a fire swept through Chicago. The flames claimed some 300 lives, destroyed around 17,500 buildings, and left more than 100,000 Chicagoans (i.e., over a third of the city’s people) homeless. According to legend, the Great Chicago Fire was sparked by a lantern kicked over by a cow belonging to Catherine O’Leary (1827–1895), an Irish immigrant. The fire’s true origin remains a mystery. But the tale of “Mrs. O’Leary’s cow” has entered popular culture, appearing in numerous songs and films. Regrettably, the story was fueled by anti-Irish sentiment. Chicago’s city council officially exonerated the O’Leary family and the infamous cow in 1997, to the relief of Mrs. O’Leary’s great-great-grandchildren.

Chicago rose from the ashes like a mythic phoenix to make its greatest contributions to human progress. After the Great Chicago Fire, the city was rebuilt around the rail industry. Chicago’s central location helped the city to contribute to the meteoric rise of rail-based commercial transportation. Recognizing Chicago’s prime location, most railroad companies building westward chose the city for their headquarters. The city thus also became a major manufacturing center for railroad equipment.

The roar of passenger and freight trains soon filled the air around the city’s six bustling inter-city terminals. Municipal and regional commuter trains also appeared and redefined intracity transport. Chicago’s Union Station still looks as it did during the Golden Age of rail and is today the United States’ third busiest train station.

Recent research suggests that the development of a nationwide transportation system, particularly railroads, helped the United States urbanize and industrialize in the 19th century. The “transportation revolution” made it easier for rural workers to relocate to urban locations and take up manufacturing work. Trains also let goods flow more quickly across the country, allowing for greater regional economic specialization. As the country’s Northeast region industrialized, the Midwest earned its nickname, “America’s Breadbasket,” by producing wheat to support the country’s swelling population.

Freight trains loaded with goods from other cities arrived at the central yards of Chicago. There, workers classified the goods. They then transferred the arrivals to massive sorting yards on the city’s outskirts.

As Chicago prospered, the city became a center of culture and innovation, with particularly notable contributions to transportation technology. As host of the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, Chicago gave humanity several new inventions. Those included the Ferris Wheel (also called the Chicago Wheel), the moving walkway, and the first third rail.

By 1900, Chicago was the fifth most populous city in the world and the second most populous in the United States, after New York City. If you could visit Chicago during the Age of Steam, you would enter a city jam-packed with pedestrians, horse-drawn carts, streetcars, and, of course, trains. Around two thousand trains, including freight trains, arrived and departed the city each day. Rail transport had come a long way from the days when people doubted whether steam-locomotives could outrace horses.

Steam transportation helped create the modern world, and no city was more central to the so-called rail revolution than Chicago. It was once commonly said that “all roads lead to Rome.” That city’s groundbreaking road system earned Rome its place as our ninth Center of Progress. Today, it could as easily be said that “all railways lead to Chicago.” For lending steam to urbanization, industrialization, and ultimately the Great Enrichment, Chicago during the Golden Age of train travel is rightly our 25th Center of Progress.