Today marks the fifteenth installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org called Centers of Progress. Where does progress happen? The story of civilization is in many ways the story of the city. It is the city that has helped to create and define the modern world. This bi-weekly column will give a short overview of urban centers that were the sites of pivotal advances in culture, economics, politics, technology, etc.

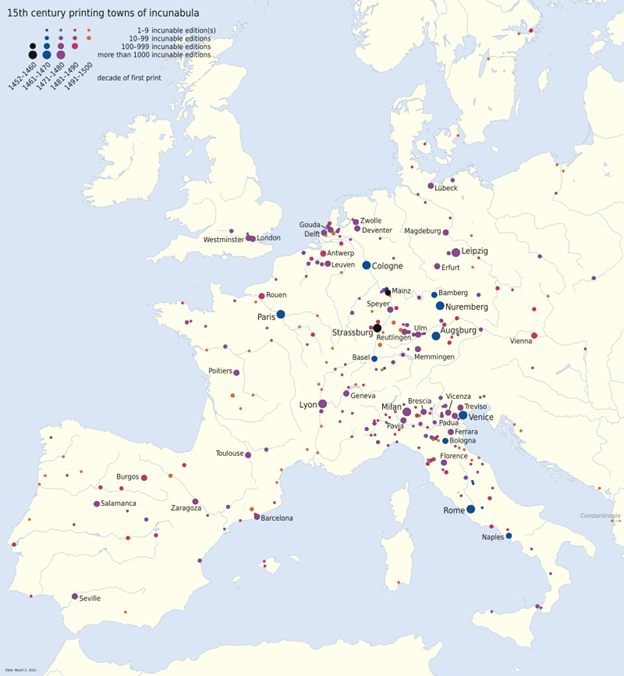

Our fifteenth Center of Progress is Mainz, the hometown of the man who invented the metal movable-type printing press, Johannes Gutenberg (circa 1399–1468), and the urban base from which that invention spread throughout Europe. While he may have technically invented the printing press in Strasbourg, Gutenberg soon returned to Mainz, and it was in the latter city that he taught many others the art of printmaking. Political turmoil in the city soon caused a mass exodus of Gutenberg’s apprentices. The printmakers spread out from Mainz to different corners of Europe, where they further disseminated printmaking knowledge. The Mainz printmaker diaspora helped increase the speed with which other parts of Europe adopted the printing press.

Today, Mainz is the capital and biggest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, a state in western Germany. The city is known for its wine production and beautiful reconstructed half-timbered houses, and its market squares’ medieval architecture. It is also a carnival stronghold: every February, during Ash Wednesday and Shrove Tuesday, the city brims with parades and music. Located on the Rhine River banks, Mainz also houses a beautiful cathedral dating back to 975 AD, as well as the Gutenberg Museum. The museum, devoted to the history of printing, was founded in 1900 AD and contains two original 15th-century Gutenberg Bibles. The city’s industries are varied and include chemical and pharmaceutical products, electronics, precision instruments, machinery, glassware, and musical instruments. Appropriately, given its history, Mainz also remains an important media center, with publishing houses as well as radio and television studios. The city also honors its most famous resident with a festival in his honor each summer, called Johannisnacht.

The Romans founded Mainz at the site of a preexisting Celtic settlement in the 1st century BC, establishing it as a military fortress outpost or castrum on their empire’s northern frontier. They named the outpost Moguntiacum, after the local Celtic deity Mogo or Mogons, likely a god of battle. The Latin name Moguntiacum eventually evolved into the German name Mainz that the city bears to this day. The Romans introduced wine-growing to the area, which remains a key local industry. The Roman conquerors also brought the Latin writing system with them—a writing system with a limited alphabet that, as we shall see, likely bolstered the eventual success of the printing press. Mainz also served as a provincial capital of the territory that the Romans called Germania Superior.

Mainz again rose to political prominence in the 9th century AD when it began to serve as the capital of the Electorate of Mainz in the Holy Roman Empire. The Holy Roman Empire was a political institution that, for centuries, united different constituent territories or kingdoms in central and western Europe in something more akin to a confederation than a true empire. Constituent principalities had their own rulers and enjoyed relative independence. The Encyclopedia Britannica calls the Holy Roman Empire, “along with the papacy, the most important institution of western Europe” during the middle ages. And the Electorate of Mainz is widely regarded as having been one of the most prestigious and influential states within the Holy Roman Empire. Mainz was the seat of the Archbishop-Elector of Mainz, the Primate of Germany. (The Primate of Germany was a historical title given to the most powerful bishop in the German-speaking areas of Europe). This archbishop acted as the archchancellor of Germany, one of the constituent kingdoms of the Holy Roman Empire, and was second in power only to the Holy Roman Emperor.

In other words, by the time that Gutenberg was born in a house situated on a corner in Christofsstraße in Mainz, in the late 14th century AD—the spot is now marked by a commemorative plaque—the city was a well-established center of political importance. But the city was deeply unstable, wracked by internal disputes and economic turmoil.

Tensions between the city’s patricians or nobility and the fast-growing merchant class were palpable throughout Mainz. In 1332, to quell a brief civil war, the Archbishop of Mainz granted the guilds representing merchants and craftsmen equal representation on the city council alongside the old nobility. But by the early 1400s, Mainz was home to more merchants and guild-members than patricians, and conflict between the groups was again frequent. In 1411, an uprising of merchants protesting special tax and customs privileges reserved to the nobility occurred. The protesting rioters set the homes of several patricians on fire. Afraid for their lives, one hundred and seventeen patricians fled Mainz amid the turmoil, including the family of the young Gutenberg. The family soon returned to Mainz, but the city only grew more troubled. Periodically fleeing Mainz was a recurring theme in the life of Gutenberg and many other Mainz residents.

The extent of instability within the city was so disruptive that it contributed to shortages of basic goods. In 1413, food became scarce throughout Mainz. As the city’s people starved, mass hunger riots broke out, resulting in much violence and property destruction. The riots prompted the Gutenberg family, and many others, to flee Mainz once again.

Gutenberg returned to Mainz, always drawn back to his hometown despite its problems. As he entered adulthood, Gutenberg found himself not quite fitting into either warring faction within the city. Many people hated him for his patrician status, which Gutenberg inherited through his father. Still, the city did not grant him the special legal privileges reserved to most patricians because his mother was a commoner by birth. Understanding his precarious position and attempting to safeguard his economic future, Gutenberg took up the metalworking trade.

By 1428, the city of Mainz teetered on the verge of bankruptcy, and the power-dispute between the patricians and guild-members entered a new phase in which the guilds seized power. As the city reeled from internal violence, tribal prejudices, and a crashing economy, many people understandably fled Mainz. Gutenberg was probably one of them, and in any case, he was living in Strasbourg by 1434.

In Strasbourg, Gutenberg transcended his era’s tribalism and strategically befriended both patricians and guildsmen, although he did not join the metalworking guild. Leveraging his connections with local officials, Gutenberg successfully pressured a visiting official from Mainz to pay him a debt that the city of Mainz owed to his family and likely used the capital to bolster his metalworking business. There is also evidence that Gutenberg briefly dabbled in the region’s prominent wine trade. It was while he lived in Strasbourg that Gutenberg probably developed the metal movable-type printing press.

It must be noted that the Chinese invented woodblock printing many centuries earlier. An inventor in Hangzhou, our twelfth Center of Progress, even devised movable-type, as early as the 11th century AD. However, several factors prevented movable print from seeing the level of widespread adoption in China that the technology achieved in Europe. Those factors ranged from the cultural importance that many Chinese placed on handwritten calligraphy to the sheer number of characters in the Chinese writing system. There are thousands of different Chinese characters. Contrastingly, German uses a limited alphabet of 26 letters, making printing the language more practical.

In 1448, Gutenberg went home to Mainz. As Alexander Hammond wrote in his profile of Gutenberg, “With the help of a loan from his brother-in-law, Arnold Gelthus, he was able to build an operating printing press in 1450.” Initially, Gutenberg marketed his innovation as a way to allow monks to reproduce religious texts at a much faster rate. He maintained two presses: one for the bible and one for commercial texts. By 1455, he printed the first 180 copies of “The Gutenberg Bible.” The printing press proved an initial success, allowing Gutenberg to take on apprentices and locally disseminate printmaking knowledge. Unfortunately, a lawsuit by an investor left him near bankruptcy.

The city of Mainz continued to deteriorate in a downward spiral, as a period of economic decline culminated in war between two rival archbishops. The Mainz Diocesan Feud, also known as the Baden-Palatine War, took place in 1461–1462. The combatants fought over the throne of the Electorate of Mainz. Following a close election to become the new Archbishop of Mainz, both Diether of Isenburg (the victor by a small margin) and Adolph of Nassau declared themselves the rightful archbishop. With the help of their respective political allies, Diether and Adolph went to war. Diether had made enemies of both the pope and the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III, and the latter two thus backed Adolph’s claim. Many people in the city of Mainz, including the city council, continued to support Diether, who refused to vacate the city or his archbishop’s throne.

Adolph and his troops sacked the city, and eventually, Adolph prevailed in seizing control. In 1465, Archbishop Adolph recognized Gutenberg’s contributions to human progress by granting him a court position and a large annual stipend, allowing Gutenberg to live the rest of his days in relative peace and comfort in Mainz, where he is buried.

If you could visit Mainz during the city’s sacking, you would have borne witness to a scene of terrifying violence and destruction. You also would have seen an exodus of the city’s people fleeing. Some of those people carried with them knowledge that would change history.

Almost all of the Centers of Progress featured to date have contributed to progress during ages of relative peace and prosperity, but in Mainz, that was not the case. Instead, the city’s instability became a catalyst for change. The city’s economic and political turmoil drove many craftsmen into exile from the city, including Gutenberg’s printing apprentices, thus spreading the knowledge of the art of printing throughout the European continent with incredible speed.

According to some estimates, by the 1470s, a mere decade later, every major European city had printing companies, and by the 1500s, around four million books had been printed and sold. The ability to reproduce the written word so quickly brought the spread of new ideas. Ranging from the Protestant Reformation to the later Enlightenment and the rise of new forms of government, several massive societal transformations came about largely because of the possibilities presented by the printed word.

“Every time the cost of media declines rapidly, you enable more people to speak out, and you have a greater diversity of voices,” according to the American historian Bill Kovarik, explaining that this impacts the distribution of power in society and sparks social change. Today, the digital revolution has further lowered the cost of disseminating ideas and knowledge, continuing the revolution in communications that began with Gutenberg’s Mainz printing shop.

Plagued by violence and economic problems, Mainz during the 15th century was an unlikely site of progress. But the invention that spread with incredible speed thanks to the diaspora of printmakers fleeing the city was pivotal to the future of human progress. The printing press ultimately helped erode the power of the guilds and the nobility, the very same warring factions that caused so much turmoil in Mainz. By democratizing the spread of information, the printing press enabled the proliferation of everything from scientific and medical texts to philosophical and political treatises. For those reasons, Mainz, the city responsible for Europe’s rapid adoption of the printing press, is our fifteenth Center of Progress.