Summary: Energy is indispensable for societal progress and well-being, yet many regions, particularly in the Global South, lack reliable electricity access. Traditional approaches to electrification, often reliant on charity or government aid, have struggled to address these issues effectively. However, a unique solution is emerging through bitcoin mining, where miners leverage excess energy to power their operations. This approach bypasses traditional barriers to energy access, offering a decentralized and financially sustainable solution.

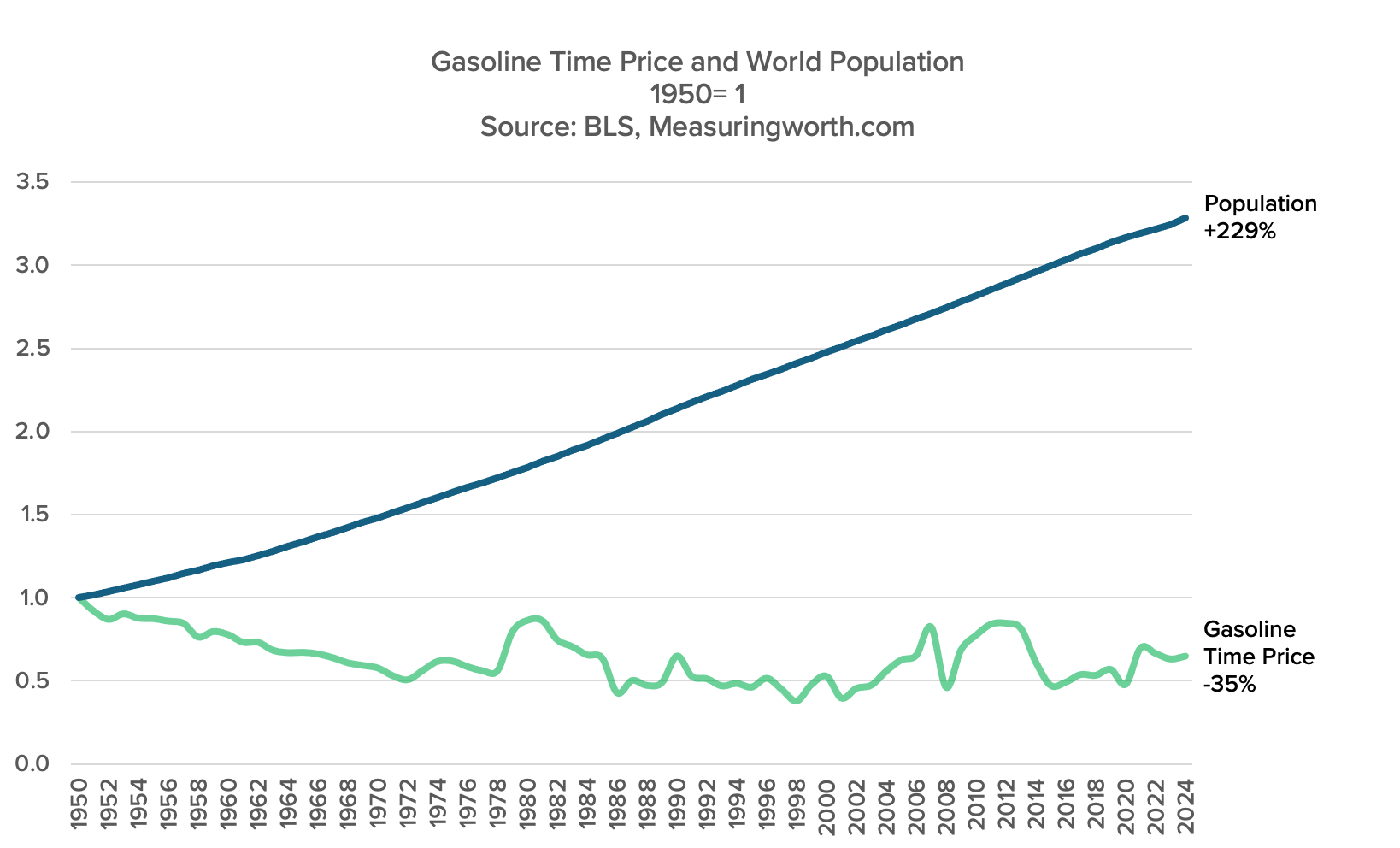

Energy is life. For the world and its inhabitants to live better lives—freer, richer, safer, nicer, and more comfortable lives—the world needs more energy, not less. There are no rich, low-energy countries and no poor, high-energy countries.

“Energy is the only universal currency; it is necessary for getting anything done,” in Canadian-Czech energy theorist Vaclav Smil’s iconic words.

In an October 2023 report for the Alliance for Responsible Citizenship on how to bring electricity to the world’s poorest 800 million people, Robert Bryce, author of A Question of Power: Electricity and the Wealth of Nations, sums it as follows:

Electricity matters because it is the ultimate poverty killer. No matter where you look, as electricity use has increased, so has economic growth. Having electricity does not guarantee wealth. But its absence almost always means poverty. Indeed, electricity and economic growth go hand in hand.

To supply electricity on demand to many of those people, especially in the Global South, grids need to be built in the first place and then have enough extra capacity to ramp up production when needed. That requires overbuilding, which is expensive and wasteful, and the many consumers of the Global South are poor.

Adding to the trouble are the abysmal formal institutions of property rights and rule of law in many African countries, and the layout of the land becomes familiar: corruption and fickle property rights make foreign, long-term investments basically impossible; poor populations mean that local purchasing power is low and usually not worth the investment risk.

What’s left are slow-moving charity and bureaucratic government development aid, both of which suffer from terrible incentives, lack of ownership, and running into their own sort of self-serving corruption.

In “Stranded,” a long-read for Bitcoin Magazine, Human Rights Foundation’s Alex Gladstein accounted for his journey into the mushrooming electricity grids of sub-Saharan Africa: “Africa remains largely unable to harness these natural resources for its economic growth. A river might run through it, but human development in the region has been painfully reliant on charity or expensive foreign borrowing.”

Stable supply of electricity requires overbuilding; overbuilding requires stable property rights and rich enough consumers over which to spread out the costs and financially recoup the investment over time. Such conditions are rare. Thus, the electricity-generating capacity won’t be built in the first place, and most of Africa becomes dark when the sun sets.

Gladstein reports that a small hydro plant in the foothills of Mount Mulanje in Malawi, even though it was built and financed by the Scottish government, still supplies exorbitantly expensive electricity—around 90 cents per kilowatt hour—with most of its electricity-generating capacity going to waste.

What if there were an electricity user, a consumer-of-last-resort, that could scoop up any excess electricity and disengage at a moment’s notice if the population needed that power for lights and heating and cooking? A consumer that could co-locate with the power plants and thus avoid having to build out miles of transmission lines.

With that kind of support consumer—guaranteeing revenue by swallowing any excess generation, even before any local homes have been connected—the financial viability of the power plants could make the construction actually happen. It pays for itself right off the bat, regardless of transmissions or the disposable income of nearby consumers.

If so, we could bootstrap an electricity grid in the poorest areas of the world where neither capitalism nor central planning, neither charity worker nor industrialist, has managed to go. That consumer of last resort could accelerate electrification of the world’s poorest and monetize their energy resilience. That’s what Gladstein went to Africa to investigate the bourgeoning industry of bitcoin miners electrifying the continent.

Bitcoin Saves the World: Energy-Poverty Edition

Africa is used to large enterprises digging for minerals. The bitcoin miners springing forth all over the continent are different. They don’t need to move massive amounts of land and soil and don’t pollute nearby rivers. They operate by running machines that guess large numbers, which is the cryptographic method that secures bitcoin and confirms its transaction blocks. All they need to operate is electricity and an internet connection.

By co-locating and building with electricity generation, bitcoin miners remove some major obstacles to bringing power to the world’s poorest billion. In the rural area of Malawi that Gladstein visited, there was nowhere to offload the expensive hydro power and no financing to connect more households or build transmission lines to faraway urban areas: “The excess electricity couldn’t be sold, so the power stations built machines that existed solely to suck up the unused power.”

Bitcoin miners are in a globally competitive race to unlock patches of unused energy everywhere, so in came Gridless, an off-grid bitcoin miner with facilities in Kenya and Malawi. Any excess power generation in these regions is now comfortably eaten up by the company’s onsite mining machines—the utility company receiving its profit share straight in a bitcoin wallet of its own control, no banks or governments blocking or delaying international payments, and no surprise government currency devaluations undercutting its purchasing power.

No aid, no government, no charity; just profit-seeking bitcoiners trying to soak up underused energy. Gladstein observes:

One night during my visit to Bondo, Carl asked me to pause as the sunset was fading, to look at the hills around us: the lights were all turning on, all across the foothills of Mt. Mulanje. It was a powerful sight to see, and staggering to think that Bitcoin is helping to make it happen as it converts wasted energy into human progress. . . .

Bitcoin is often framed by critics as a waste of energy. But in Bondo, like in so many other places around the world, it becomes blazingly clear that if you aren’t mining Bitcoin, you are wasting energy. What was once a pitfall is now an opportunity.

For decades, our central-planning mindset had us “help” the Global South by directing resources there—building things we thought Africans needed, sending money to (mostly) corrupt leaders in the hopes that schools be built or economic growth be kick-started. We squandered billions in goodhearted nongovernmental organization projects.

Even for an astute and serious energy commentator as Bryce, not once in his 40-page report on how to electrify the Global South did it occur to him that bitcoin miners—the very people who are turning the lights on for the poorest in the world—could play a crucial role in achieving that.

It’s so counterintuitive and yet, once you see it, so obvious. In the end, says Gladstein, it won’t be the United Nations or rich philanthropists that electrifies Africa “but an open-source software network, with no known inventor, and controlled by no company or government.”