Today marks the 48th installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org titled Heroes of Progress. This bi-weekly column provides a short introduction to heroes who have made an extraordinary contribution to the well-being of humanity. You can find the 47th part of this series here.

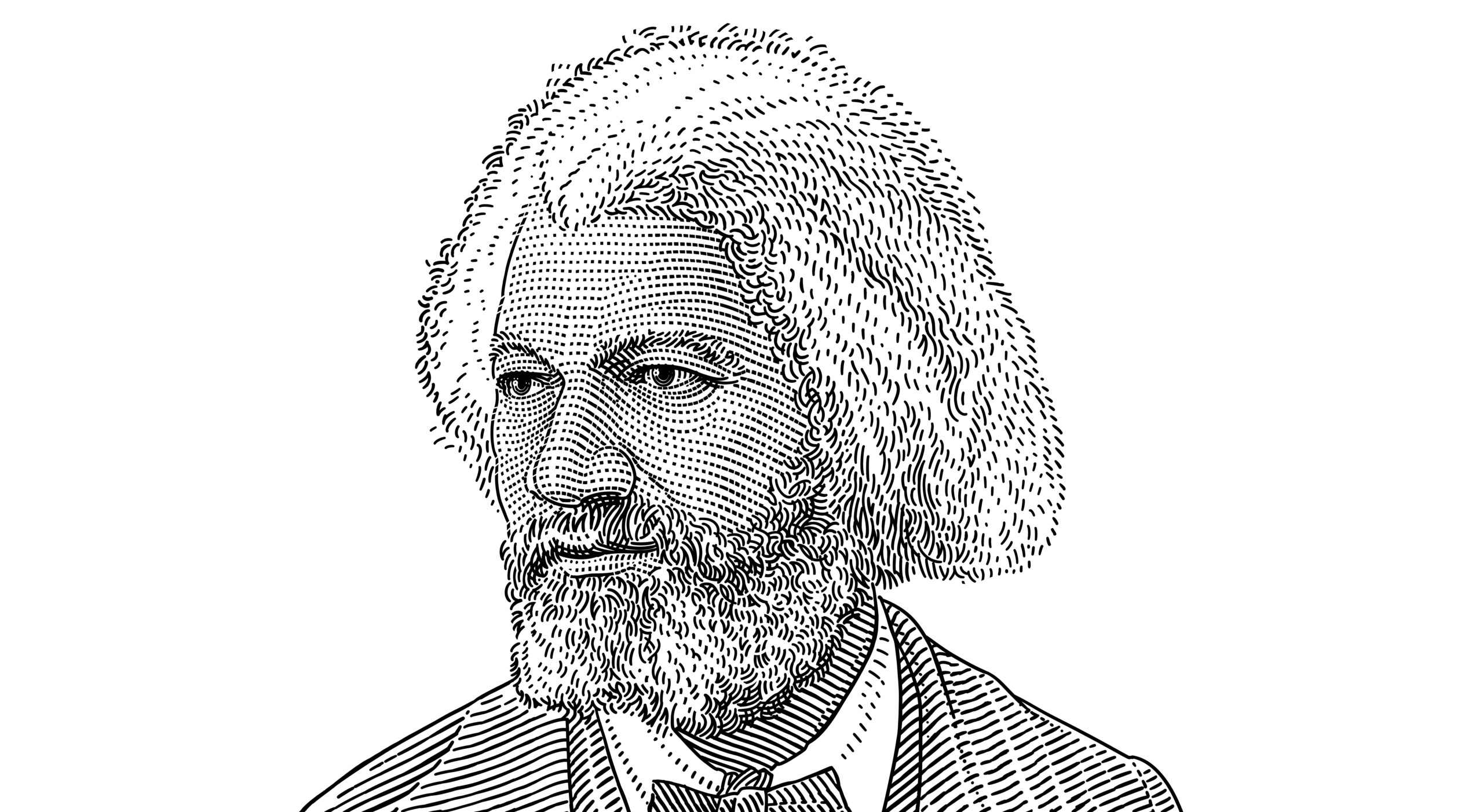

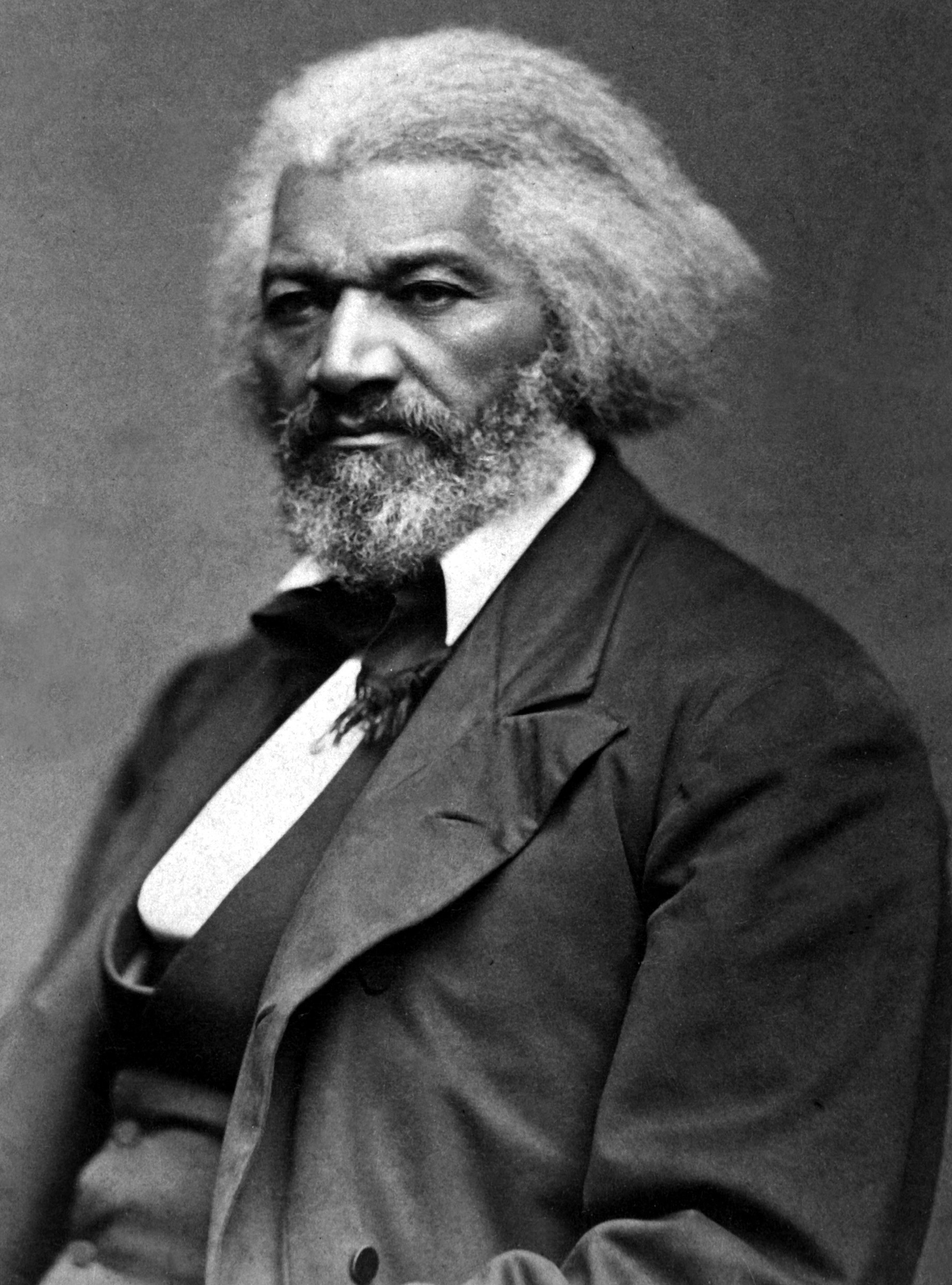

This week our hero is Frederick Douglass – the abolitionist and social reformer, who is widely considered to be one of the foremost human rights leaders of the 19th century. As a former slave who became a consultant to the U.S. President Abraham Lincoln and, later, President Andrew Johnson, Douglass helped to convince both presidents of the necessity of equal rights for black Americans.

Douglass’s relentless advocacy for equality under the law helped to shift public opinion in the United States against slavery, and his influence in the creation and ratification of the “Reconstruction Amendments” (a series of constitutional amendments that ensured equal freedom and voting rights for black Americans) led to a better and more prosperous future for millions of people.

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey (later changed to Douglass) was born a slave around 1818 in Talbot County, Maryland. As was common with slaves, the exact year and date of Douglass’s birth is unknown. Douglass later chose to celebrate his birthday on February 14th, based on his memory of his enslaved mother, who called him her “little valentine.” Douglass was separated from his mother when he was an infant and only saw her a few times before her death in 1825.

Until the age of 6, Douglass was raised by his grandmother, who was also a slave. In 1824, Douglass was moved to a plantation where Aaron Anthony, a white man whom Douglass suspected might be his father, worked as an overseer. Throughout his early life, Douglass was transferred between many different plantations. After Anthony’s death in 1826, Douglass was given to Thomas Auld, who sent him to serve his brother, Hugh Auld, in Baltimore.

When Douglass was 12, Hugh Auld’s wife, Sophia, began teaching Douglass the alphabet. Sophia made sure that Douglass was properly fed, clothed and slept in a comfortable bed. However, over time, Hugh Auld was successful in convincing his wife that slaves should not be educated. Education, he thought, would encourage slaves to desire freedom. Before long, Douglas’s lessons stopped.

Despite that setback, Douglass continued to secretly teach himself how to read and write. He found a variety of newspapers, pamphlets, books and political materials that helped him with his education and development of personal views on freedom and human rights. A couple of years later, Douglass moved to another plantation. He began hosting a weekly Sunday school, where he taught other slaves basic literacy. The plantation owner did not mind Douglass’s Sunday school, but other plantation owners became increasingly agitated at the idea of slaves being educated. One Sunday, armed with clubs, the neighboring plantation owners burst in on the gathering and disbanded it.

In 1833, Douglass was sent to work for Edward Covey, a poor and brutal farmer with a reputation for harshly beating slaves. Covey would often beat Douglass. After the whippings became more intense, Douglass, aged just 16 at the time, fought back. Douglass won and Covey never attempted to beat him again. Douglass saw the fight as a life-changing event and he introduced the tale in his autobiography thusly “you have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man.”

Later in 1833, Douglass was transferred to work in a shipyard in Baltimore. He attempted to escape from slavery in 1833 and 1836. In 1837, Douglass met and fell in love with Anna Murray, a free black woman living in Baltimore. On September 3, 1838, Murray gave Douglass a sailor’s uniform, train tickets and identification papers from a free black seaman. Douglass successfully escaped from Maryland by taking a train and a steamboat north to New York City.

After eleven days in New York, Frederick and Anna married and resettled in New Bedford Massachusetts, which had a large free black community. Initially, the couple adopted the name Johnson. Later, they changed it to Douglass in an effort to elude slave hunters, who were after Frederick.

In 1839, Douglass became a licensed preacher, which helped him hone his public speaking skills. He also started to attend meetings and protests organized by abolitionist groups. In 1841, Douglass was invited to speak at an antislavery convention in Nantucket, Massachusetts. The speech went so well that Douglass was invited to work as an agent and speaker for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society.

In 1843, Douglass went on a six-month speaking tour with the American Anti-Slavery Society across the Eastern and Mid-Western United States. During the tour, the group was often met with violent protests. Many skeptics doubted that Douglass’s story was real, arguing that a former slave could not be such an articulate orator.

That criticism led Douglass to write an autobiography in 1845, titled Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. The book became an immediate bestseller and was quickly translated and published across Europe. Throughout his life, Douglass published three versions of his autobiography.

Many of Douglass’s friends feared that his newfound fame would attract attention from slave hunters acting on behalf of his former master Thomas Auld. To escape potential problems, Douglass left the United States on a two-year speaking tour of Great Britain and Ireland on August 16, 1845.

During his time in Ireland and Great Britain, Douglass was amazed by the lack of racial discrimination. He later noted that he found himself “regarded and treated at every turn with the kindness and deference paid to white people” and that he was seen not “as a color, but as a man.”

Douglass’s speaking tour was an enormous success. Many of his new friends and supporters tried to encourage him to stay in England. With his wife still in Massachusetts and more than three million black Americans still in bondage, Douglass was adamant on returning home. Before he left the British Isles, his supporters raised enough money for Douglass to buy his freedom.

In 1847, Douglass returned to the United States and immediately bought his freedom. He also began his own anti-slavery newspaper titled the North Star. In 1848, Douglass became involved in the early feminist movement and was the only African American to attend the Seneca Falls Convention, which was the first women’s rights gathering in the United States. Douglass also became an early advocate for school desegregation, arguing that the facilities for black children were vastly inferior to those for whites.

During the U.S. Civil War (1861-65), Douglass became an advisor to the U.S. President Abraham Lincoln. Douglass convinced the President that because the goal of the Civil War was to end slavery, African Americans ought to be able to fight in the war. Douglass also urged the President to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that slaves in Confederate territory would be free if they escaped to Union-controlled territory. Moreover, Douglass advised President Lincoln and, later, President Johnson, to push for a series of amendments to the U.S. Constitution that would protect the rights of black Americans.

In 1865, the 13th Amendment, which outlawed slavery, was ratified In 1868, the 14th Amendment provided citizenship and equal rights to black Americans. In 1870, the 15th Amendment prohibited federal and state governments from denying a citizen the right to vote based on race. Together, these three amendments are dubbed the “Reconstruction Amendments.”

Throughout the rest of his life, Douglass remained dedicated to equality for all. In 1870, he started his last newspaper the New National Era. In 1872, Douglass became the first black American to be nominated for Vice President of the United States on the Equal Rights Party ticket. In 1874, he was appointed as the U.S. Marshall for the District of Columbia. Throughout the 1880s, Douglass travelled the world and spoke on human rights and racial equality. At the 1888 Republican National Convention, Douglass became the first African American to receive a vote for President of the United States. From 1889 to 1891, Douglass was the consul-general to Haiti.

On February 20, 1895 Douglass died of a heart attack. He was 77 years old. Posthumously, Douglass has received dozens of awards and honors. To this day, many schools, parks, scholarships and statues are named or erected in his honor.

Douglass’s work helped shift the U.S. public opinion against slavery, and his influence helped to bring about the ratification of the Reconstruction Amendments, which for the first time provided rights to millions of African Americans. For these reasons, Frederick Douglass is our 48th Hero of Progress.