A Christmas Carol, the classic 1843 holiday tale written by the English writer Charles Dickens, is surprisingly relevant to today’s concern over overpopulation.

The well-known story deals with the transformation of wealthy London businessman Ebenezer Scrooge from a misanthropic grump into a merry fellow filled with goodwill toward his fellow man. His change of heart results from visits by four mysterious spirits: the ghost of his former colleague, the Ghost of Christmas Past, the Ghost of Christmas Present and the Ghost of Christmas Future. Early in the story, Scrooge suggests that poor people ought to die and thereby “decrease the surplus population.”

Scrooge clearly believed that there is such a thing as an excess of people. Unfortunately, far too many real people hold that belief today.

In 2019, for example, U.S. Senators, like Ed Markey (D-MA) and Chris Van Hollen (D-MD), and Representatives, like Jimmy Gomez (D-CA) and Susie Lee (D-NV), tweeted their support for a paper explicitly calling for the reduction of the world’s population. Also this year, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) questioned whether it is morally acceptable to have children and Senator Bernie Sanders (D-VT) endorsed population control. This past summer, in the country where A Christmas Carol is set, Prince Harry subtly suggested that children are a burden to the planet and that responsible folks should have “two, maximum.”

The idea of a “surplus population” predates Dickens’s novel, harking back to antiquity and, in its early modern iteration, Thomas Malthus’s 1798 work An Essay on the Principle of Population. Malthus’s idea—that too many people would deplete resources and lead to scarcity—was popular among British intellectuals when Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol. Indeed, in 1840s England, the concept of overpopulation seemed more relevant than ever as the population of London swelled.

During the 19th century, London became the world’s most populous city. London’s population grew from 1 million in 1800 to over 2 million by the time A Christmas Carol was published, and to 6.5 million by the end of the 19th century. London’s population grew partly due to urbanization, as people fled the countryside to work in factories. While the factory conditions were often harsh, millions of Britons found them preferable to the backbreaking agricultural labor and monotony of rural life.

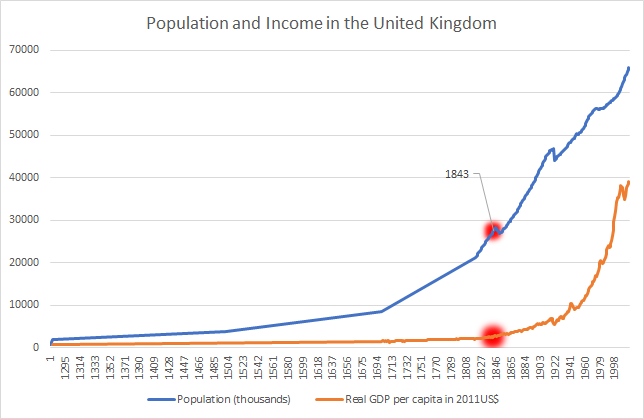

London’s population also grew because the United Kingdom as a whole was expanding. A Christmas Carol suggests that Scrooge is in his 60s or 70s, argues Stanford University English professor Claire Jarvis. That means that during his lifetime the character would have seen his country’s population increase by about a third. There were fewer than 20 million people in the country when Scrooge’s character was “born.” By 1843, however, the country’s population stood at over 27.5 million.

That was, the Nobel Prize-winning economist Angus Deaton argues, due to the spread of new knowledge and medical advances, including the spread of variolation and inoculation against smallpox, first among the nobility and, later, among commoners. To get a sense of how deadly Victorian England was, note that a child in sub-Saharan Africa today enjoys better odds of living to the age of five than a Victorian child did. As fewer people died, the population grew.

Writer and economist Jerry Bowyer has argued in Forbes that with A Christmas Carol, Dickens was weighing in on a central economic debate of his time. That is, the debate between Malthusians and the disciples of the Scottish economist Adam Smith, like the French economist Jean Baptiste Say, who argued that peaceful market exchange could create prosperity and meet the needs of a growing populace. Say was right. As the chart above shows, British population growth coincided with massive enrichment.

The debate over “overpopulation,” has continued to rage on, more recently between neo-Malthusians like the Stanford University biologist Paul Ehrlich and rational optimists like the late University of Maryland economist Julian Simon. The latter’s insight was that human beings themselves are the “ultimate resource” making all other resources more plentiful. (Recent research lends support to Simon’s ideas).

The Ghost of Christmas Present represents the opposite of Malthusian scarcity. He first appears to Scrooge on a “throne” made of overflowing food: “turkeys, geese, game, poultry, brawn, great joints of meat, sucking-pigs, long wreaths of sausages, mince-pies, plum-puddings, barrels of oysters, red-hot chestnuts, cherry-cheeked apples, juicy oranges, luscious pears, immense twelfth-cakes, and seething bowls of punch.” The spirit carries a torch shaped like “Plenty’s horn,” meaning a cornucopia, the emblem of abundance, and an empty, swordless scabbard, symbolizing peace.

The Ghost claims he has “more than eighteen hundred” brothers, representing previous Christmases (again, the book came out in the year 1843). Upon hearing that, Scrooge’s mind, in true Malthusian fashion, immediately turns to scarcity. “A tremendous family to provide for!” mutters Scrooge. The Ghost then whisks Scrooge to a marketplace to show him this scene of Smithian abundance:

“There were great, round, pot-bellied baskets of chestnuts … There were ruddy, brown-faced, broad-girthed Spanish Onions … There were pears and apples, clustered high in blooming pyramids; there were bunches of grapes, made, in the shopkeepers’ benevolence to dangle from conspicuous hooks … there were piles of filberts … there were Norfolk Biffins [a kind of apple] setting off the yellow of the oranges and lemons … The[re were] gold and silver fish, set forth among these choice fruits in a bowl.”

In the marketplace, Scrooge observes the literal fruits of international commerce. Trade allowed Victorian Englishmen and Englishwomen to enjoy oranges, lemons and grapes in midwinter. The Ghost of Christmas Present then shows Scrooge the family of one of his employees having Christmas dinner. Even that impoverished family is shown enjoying oranges.

When Scrooge inquires about whether the family’s ill child, Tiny Tim, will survive, the Ghost of Christmas Present taunts Scrooge by repeating Scrooge’s words back at him: “What then? If he be like to die, he had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.” Scrooge then begins to feel shame at having questioned the worth of “surplus” human beings.

Today, globalization has taken Smith’s ideal of peaceful exchange to a new level, increasing worldwide prosperity. Even as the world’s population has climbed to an all-time high, hunger has reached an all-time low. Yet Malthusianism continues to haunt public discourse and enjoys surprising popularity. Dickens would agree that it’s time, as the saying goes, to lay that ghost to rest.