For many decades, critics of economic development argued that rising incomes and greater material abundance did not lead to higher levels of happiness. In 1974, Richard Easterlin from the University of Southern California noted that people in richer countries were not happier than people in poor countries. Subsequent research found that the so-called Easterlin Paradox did not exist. Instead, happiness seems to increase with affluence. Today, a different kind of criticism is gaining round. Happiness may be increasing, the critics of economic development concede, but life in a modern capitalist society is more and more devoid of meaning. What are we to make of this criticism?

Writing in New York Magazine, Andrew Sullivan notes, “As we have slowly and surely attained more progress, we have lost something that undergirds all of it: meaning, cohesion, and a different, deeper kind of happiness than the satiation of all our earthly needs. We’ve forgotten the human flourishing that comes from a common idea of virtue, and a concept of virtue that is based on our nature.” Why, he asks, is there “so much profound discontent, depression, drug abuse, despair, addiction, and loneliness in the most advanced liberal societies”? And, he concludes, “For our civilisation, God is dead… We have no common concept of human flourishing apart from materialism, and therefore we stand alone.”

Let us start by unpacking the difference between happiness and meaning. As Steven Pinker observes in his book Enlightenment Now, “We can make choices that leave us unhappy in the short term but fulfilled over the course of a life, such as raising a child, writing a book, or fighting for a worthy cause… People who lead happy but not necessarily meaningful lives have all their needs satisfied: they are healthy, have enough money, and feel good a lot of the time. People who lead meaningful lives may enjoy none of these boons. Happy people live in the present; those with meaningful lives have a narrative about their past and a plan for the future.”

Happiness, then, isn’t everything. But surely it is better to search for the meaning of life on a full, rather than an empty, stomach. And if it happens that the search for meaning requires fasting, let it be undertaken freely rather than as a compulsion. Economic development increases the scope of life choices that are available to individuals. Whether those individuals make use of the increasing number of opportunities to achieve meaningful ends is up to them.

To complicate matters, meaning is different for everyone. Who is to say that the satisfaction I derive from writing an article about the differences between happiness and meaning is truly meaningful? And is my satisfaction as meaningful as the satisfaction of someone who has just completed an extensive stamp collection?

Unlike happiness, which must, by definition, culminate in ecstasy, meaning is infinite and, therefore, impossible to measure. Sullivan, for example, points to the opioid epidemic in America as an example of “profound discontent, depression, drug abuse, despair, addiction, and loneliness.” It is certainly true, as the Princeton University economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton found, that mortality rates among poor whites in the United States have dramatically increased “due to both rises in the number of ‘deaths of despair’ – death by drugs, alcohol and suicide – and to a slowdown in progress against mortality from heart disease and cancer, the two largest killers in middle age.”

But the two authors also found that “midlife mortality rates continue to fall among all education classes in most of the rich world.” Perhaps the opioid crisis among poor whites, who voted in large numbers for Donald J. Trump in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, should have been of greater concern to previous administrations. But do the growing problems experienced by a particular group of Americans mean that the whole of America is suffering from existential angst? And to what extent is despair of poor white Americans representative of the state of the Western world? The data, alas, is devilishly difficult to come by.

The extent to which the West suffers from the crisis of meaning is less than clear. But, even if the problem is a serious one, is democratic capitalism to blame? Did modern-day liberalism kill God and destroy the “common concept of human flourishing apart from materialism”? No one, after all, prevents individuals from finding God on their own or from obtaining a sense of communal belonging by associating with people who have had a similar spiritual experience.

Likewise, complaints about meaningless pursuit of earthly pleasures (materialism) are a recurrent theme in Western writing. Edward Gibbon, to give just one example, refers to “licentiousness” as an important source of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire no fewer than 131 times.

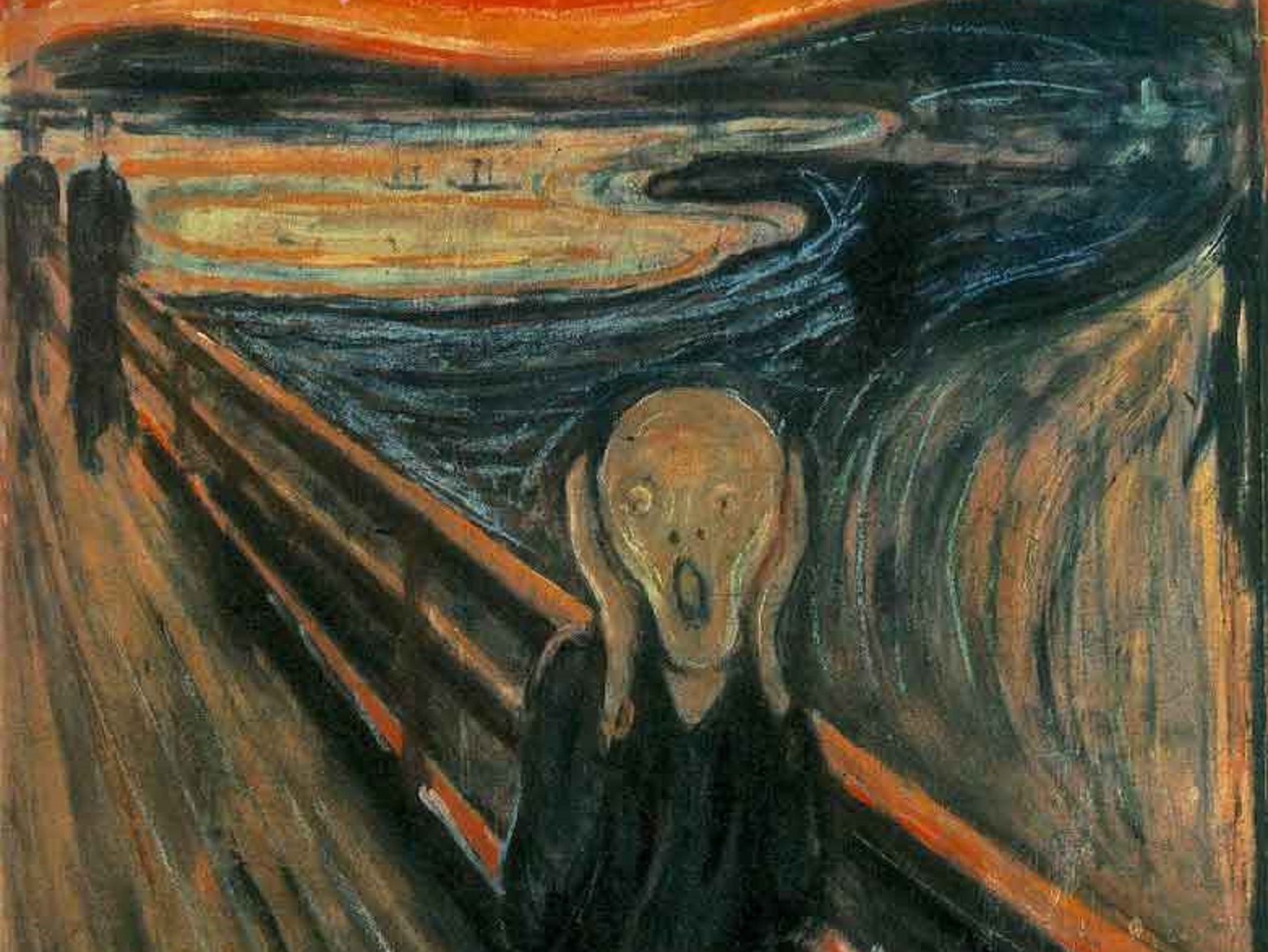

Societies, it seems, go through crises of confidence periodically. As my colleague Jason Kuznicki reminded me, the art (Dadaism) and the literature (F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel The Great Gatsby) of the 1920s point to a very deep sense of alienation and the loss of meaning that resulted from the carnage of World War I.

A century later, we may well be, as Sullivan writes, in the midst of a similar episode. If so, history suggests that we shall overcome our civilisational angst once more, though, perhaps, we can do so without the false hope of fascism. Lest it be forgotten, in spite of the horrors of the 20th century, humanity has entered the new millennium more numerous, longer-living, richer, healthier, more educated and, even, more peaceful than ever before.

This first appeared in CapX.