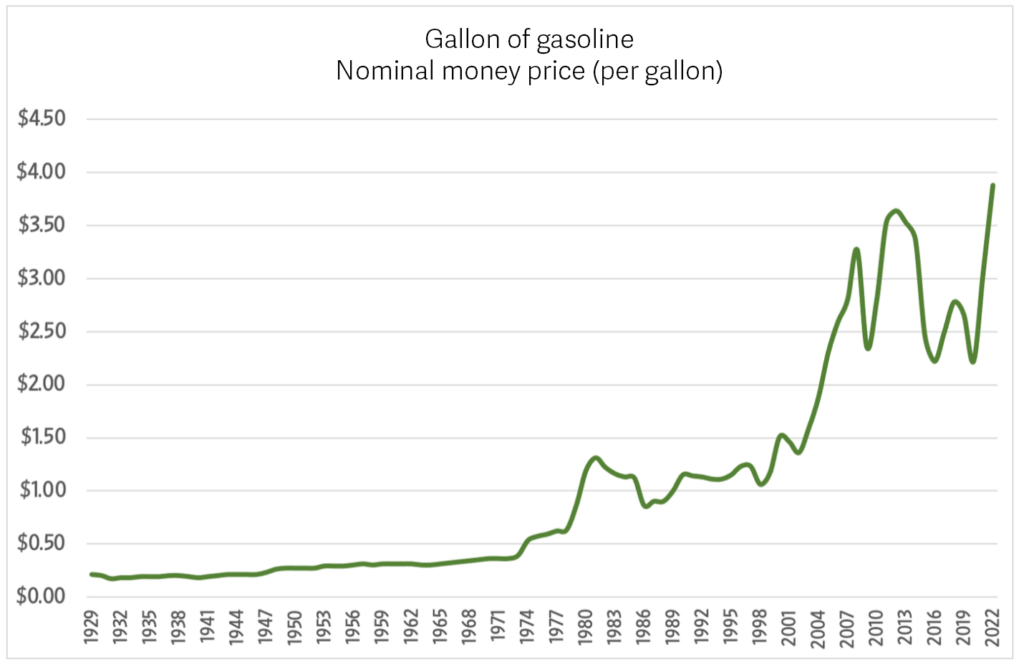

USA Today recently reported that gas prices are the most expensive that they’ve been in U.S. history, breaking the record from 2008. The U.S. Energy Information Administration notes that the average price of a gallon of gasoline reached $4.22 in April 2022, the highest nominal price ever and 16 cents higher than the previous record of $4.06 in July 2008.

But does the nominal money price really reveal the true price? Since we buy things with money, but we pay for them with our time, there are actually two prices: money prices and time prices. Money prices are expressed in dollars and cents, while time prices are expressed in hours and minutes. Converting a money price to a time price is simple. Divide the money price of a product or service by hourly income. As long as hourly income increases faster than the money price, the time price will decrease.

To calculate the time price of a gallon of gasoline we divided the nominal money price by nominal blue-collar hourly compensation (wages and benefits) as reported by the economic data website measuringworth.com. When we look at the time price of a gallon of gasoline, we see a much different story.

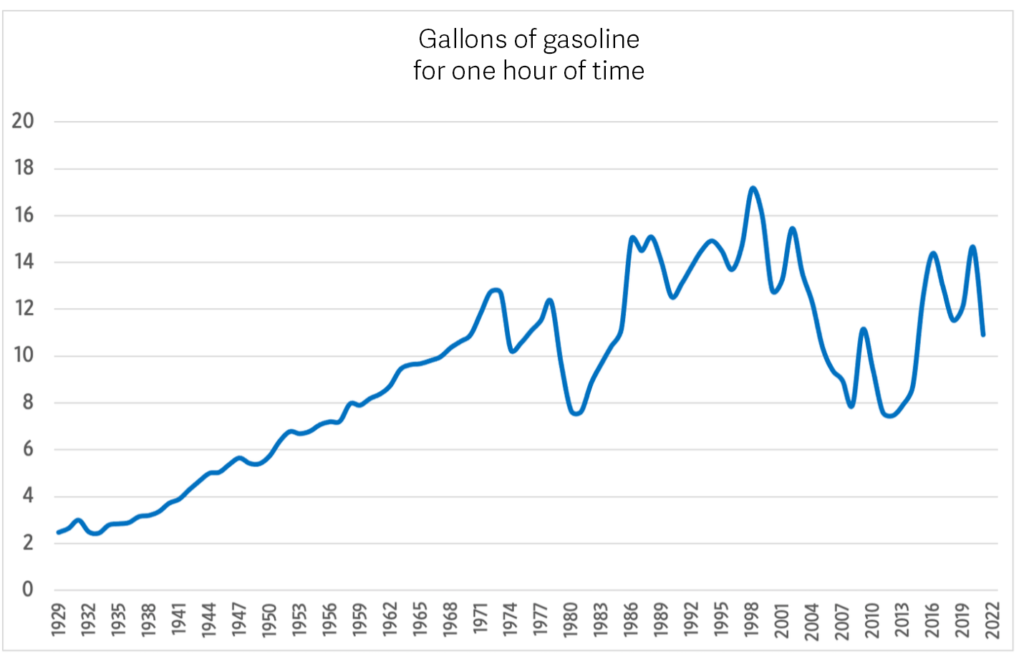

In 1929 it took about 24 minutes to earn the money to buy one gallon of gasoline. Today the time price is closer to 6 minutes. The time price of gasoline has dropped by 75 percent. For the time it took to earn the money to buy one gallon in 1929, you can buy four gallons today. Gasoline abundance has increased by 300 percent. This occurred while the global population increased 290 percent, from 2 billion to 7.8 billion. The greater the population, the more abundant gasoline has become.

Another interesting way to think about the time price of a resource is to consider how many gallons of gasoline one hour of time would buy. Call this gallons per hour or GPH. This ratio reveals how much abundance is changing over time.

In 1929 one hour of time would get you around 2.5 gallons. By 1973, gasoline abundance had increased 410 percent, to 12.75 gallons per hour. Then the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) cartel raised prices dramatically, so that by 1981 one hour would only get you 7.63 gallons of gasoline. Once OPEC lost its control of oil the trend reversed. By 1998 the number of gallons per hour was up to 17.15, the highest rate on record. World events reversed the trend again, and by 2012 it was back down to 7.46 gallons per hour, lower than what it had been in 1981. We then climbed out of this trough and were back up to 14.66 GPH in 2020. The COVID-19 policies have knocked us off course over the last two years, but the underlying fundamentals of economics suggest that we will recover and move back to around 12 gallons per hour, which is the average over the last 50 years.