Back in May, a young American called Akki caused a minor twitterstorm by seemingly showing what many pundits in the U.S. media frequently assert – that ordinary Americans are worse off today than they were in the late 1970s. A number of better educated twitterati soon pointed out that Akki, a self-declared member of #TheResistance, engaged in what former U.S. President George W. Bush once referred to as “fuzzy math.” In the meantime, Akki’s misleading claim scored over 197,000 likes on Twitter. It seems that in addition to the U.S. dollar, Americans have come to crave a new kind of currency: victimhood. Many Americans of all political persuasions relish the feeling of aggrievement and the accompanying sense of moral superiority, and if that means that they have to pretend that their lives are worse than those of their ancestors, so be it.

Per Akki, a loaf of bread in 1977 cost $0.32. In May 2019, it cost $1.98. In the meantime, the median income per person, Akki also claimed, remained the same. Ergo, Americans were worse off in 2019 than they were in 1977. The data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, the most authoritative of sources, tells a somewhat different story. The real median income per person in 1977 came to $23,202. It stood at $31,099 in 2016 (the last year for which data are available). Both figures are in 2017 dollars. So, an American in the middle of the income spectrum was about $7,897 (or 34 percent) better off in 2016 than he or she would have been in 1977. And that’s not counting the increase in non-wage benefits that, due to the quirks of the U.S. tax code, continue to expand. As for the price of bread, Akki’s $0.32 would amount to $1.36 today. Target sells a loaf of bread for $1.09.

Thanks to Akki and many other misinformed people on both sides of the political spectrum, a myth of stagnating American standards of living has arisen and continues to spread. According to South Bend mayor and 2020 Democratic presidential hopeful Pete Buttigieg, the supposed stagnation started with the election of Ronald Reagan to the U.S. presidency in 1980. But, of course! “What we’ve seen is that the rising tide rose, right? GDP went up. Growth went up. Productivity went up — big numbers went up and most of our boats didn’t budge. For 90 percent of Americans, you start the clock right around the time I’m born [1982]. Income didn’t move at all — so lower to middle income, really, almost all of us,” Buttigieg said.

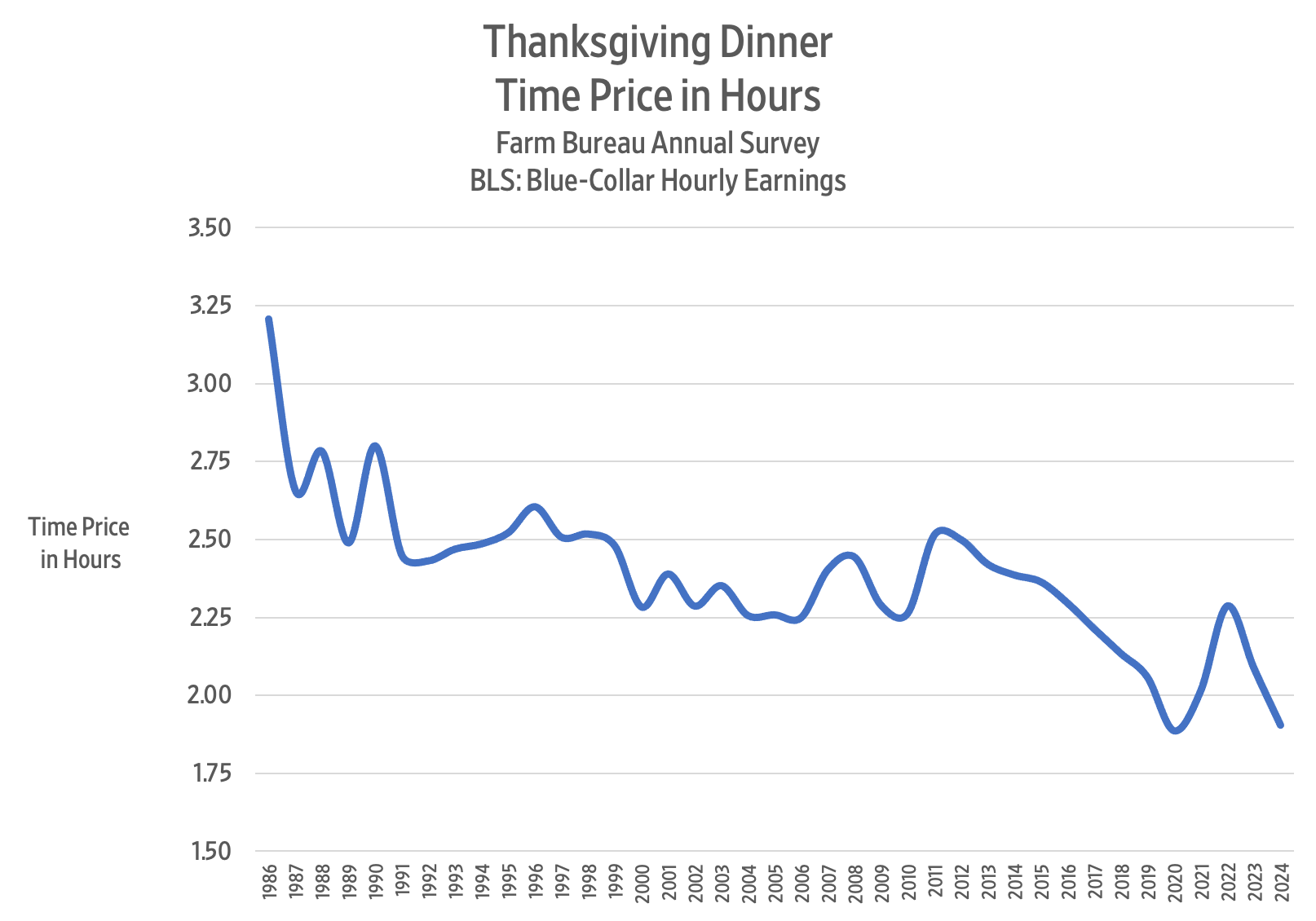

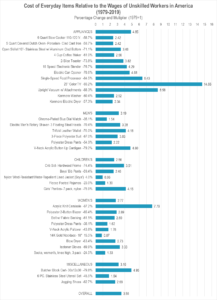

Having shown the massively decreasing cost of food in the United States in previous columns, I shall now turn to the cost of other everyday items, including appliances and clothing, between 1979 (the year before Reagan’s election) and 2019. Together with Gale Pooley, associate professor of business management at Brigham Young University-Hawaii, I looked at the prices of everyday items as they appeared in the 1979 Sears Christmas Book and compared them to the prices of identical (or almost identical) items as they appeared on Walmart’s website in 2019. We then divided the Sears’ prices by the hourly wage of unskilled workers in 1979 ($3.69) and Walmart’s prices by the hourly wage of unskilled workers in 2019 ($12.78).

The average time price (i.e., the amount of time that a person has to work in order to earn enough money to buy something) of everyday items relative to the hourly wages of unskilled workers declined by 72 percent. It declined by 75 percent for skilled workers and by 89 percent for upskilling workers (i.e., workers who started as unskilled workers in 1979, but ended up as skilled workers in 2019). That means that for the same amount of work that allowed an unskilled worker to purchase one item in our basket of everyday items in 1979, he or she could buy 3.56 items in 2019 (on average). A skilled worker’s purchasing power increased from one to four and upskilling worker’s purchasing power increased from one to nine.

There are a lot of reasons for the rise of populism in the West, but one, almost trite, reason is often overlooked. Our schools and our media not only fail to educate the citizenry; they actively mis-educate the electorate. Instead of showing the unbelievable progress that humanity has made since the start of the Enlightenment some three centuries ago, history classes, to the extent that history is still taught, are used to whip up resentment and a sense of victimhood among different socio-economic, racial, ethnic, religious and gender groups. The media breathlessly repeat stories of (real and imagined) oppression and (supposed) economic retrenchment, even though people in the West currently enjoy a period of unprecedented peace and prosperity. Akki’s tweet is but a tiny part of a broader trend of victimhood-Olympics.

So, to the question that is so often raised by so many talking-heads on television, professors in the classroom and politicians making stump speeches – Why populism? – I have only one answer: look in the mirror.

This first appeared in CapX.