As every parent knows, infancy and childhood can be fraught with peril. From Sudden Infant Death Syndrome to suffocation, the list of dangers to infants is extensive. But the risks today pale in comparison to those that children faced in the past.

Judith Flanders’ exhaustively detailed book, Inside the Victorian Home: a Portrait of Domestic Life in Victorian England, offers a disturbing glimpse of early childhood in the Victorian era. It should fill everyone with gratitude for the sheer scale of medical advancement in the last century or so.

The benefits of vaccines and proper sanitation are, of course, well-known. However, the sheer extent of their positive impact on the lives of children bears repeating. Before the age of five, 35 out of every 45 Victorian children had experienced either smallpox, measles, scarlet fever, diphtheria, whooping cough, typhus or enteric fever — or some combination of those illnesses — and many of them did not survive.

As late as 1899, more than 16 percent of children died before their first birthday; today in the United Kingdom that figure is 0.35 percent.

What is less well known is that it was not just disease, but also primitive medicine that killed infants.

Consider teething and one of its alleged cures. Today, teething is accepted as a routine stage of development. In Victorian England, it was not. According to the common wisdom of the age, teething was a potentially deadly disorder, sometimes involving convulsions, and should be treated with opium.

Giving opium to an infant is a very bad idea, causing — you guessed it — convulsions and often death. A shocking 16 percent of child deaths in Victorian England were the result of well-meaning attempts to treat teething with opium. Parents attributed these opium-induced deaths to teething and blamed themselves for failing to have administered a high enough dose of the opium “cure”.

Childhood ailments, real and imagined, were often treated with hard liquor, such as brandy, or milder alcoholic drinks, like wine. Patent medicines were also popular. John Collis Browne’s Cholodyne, for example, which was supposed to have cured everything from colds and coughs to stomach aches and sleeplessness, contained cannabis and a hypnotic drug called chloral hydrate in addition to opium.

Other common cures included ipecacuanha, a powdered root that induces vomiting; and the laxative calomel, made of mercury chloride, which is highly toxic. Newborns were also routinely given castor oil (a laxative later famously force-fed to prisoners in Mussolini’s Italy) shortly after birth.

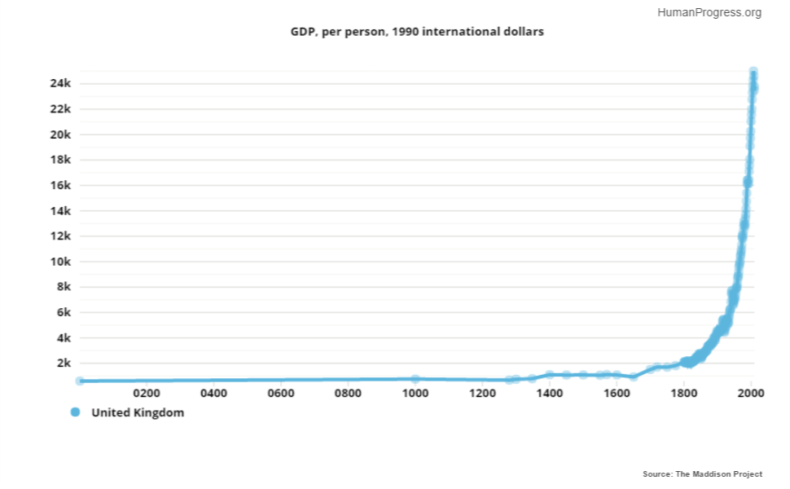

It should be noted that, as horrid as Victorian medical practices were, child mortality rates fell dramatically as better urban sanitation and scientific understanding of disease spread. Medical practices weren’t the only part of Victorian childhoods that might today be considered abusive, or at least troubling. Childhood discipline practices, it turns out, have also evolved quite a bit since the Victorian era.

As Flanders writes, our understanding of “what seemed harsh changed over time”. Some Victorian parents held their children’s fingers against hot fireplace grates and cut them with knives, to teach them the dangers of fire and sharp objects. Corporal punishment, even including whipping, was still common, although it gradually vanished over the course of a century.

Children were denied any food that they enjoyed. Food that tasted good enough to be consumed because of desire rather than hunger was considered morally damaging to the young. Eggs, bacon, and other flavorful foods were thought to be the gateway drugs to a life of hedonism and sin.

Even children from prosperous families grew up on a Spartan diet of bread, porridge and watered-down milk. The wealthy Gwen Raveat née Darwin, a granddaughter of Charles Darwin and the daughter of a Cambridge University don, recalled that during her childhood, twice a week she was allowed toast “spread with a thin layer of that dangerous luxury, jam. But of course, not butter too. Butter and jam on the same bit of bread would have been an unheard-of indulgence — a disgraceful orgy.”

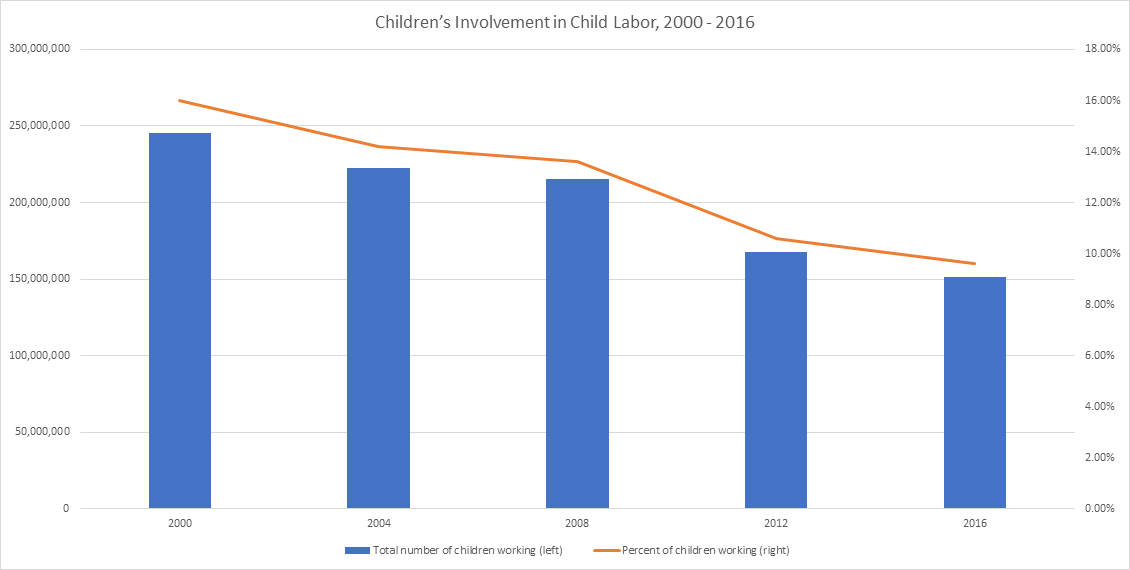

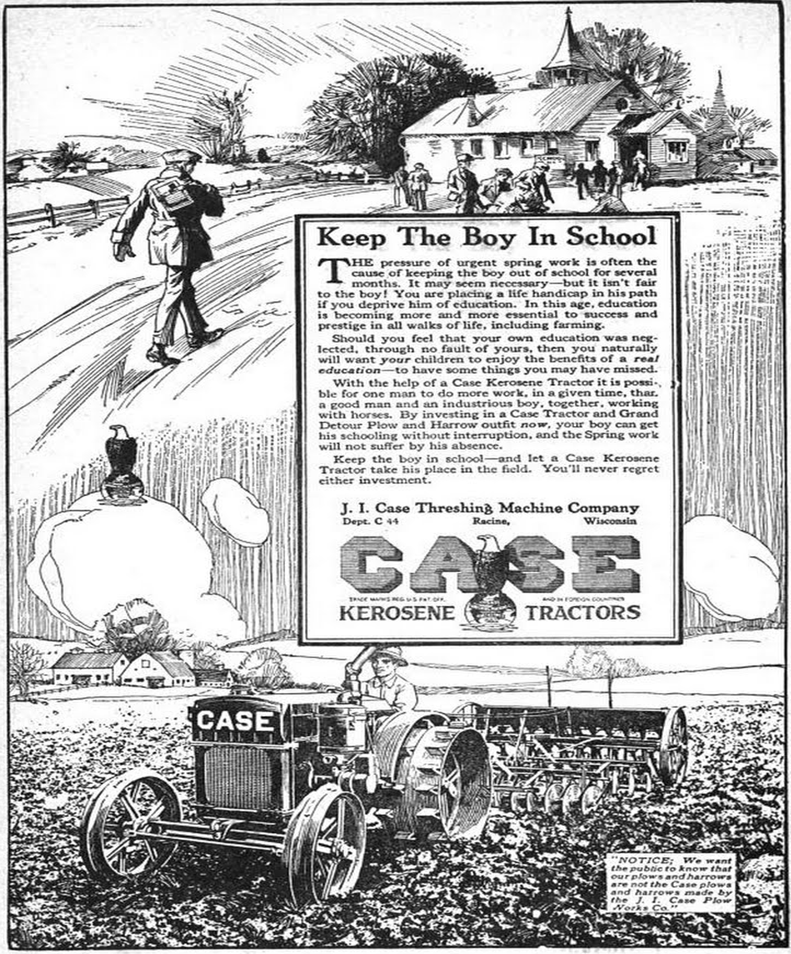

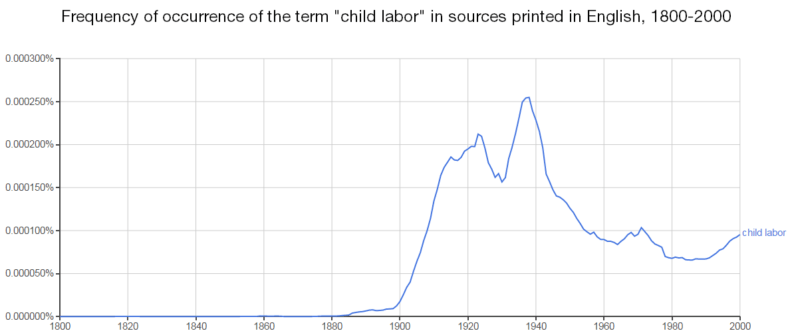

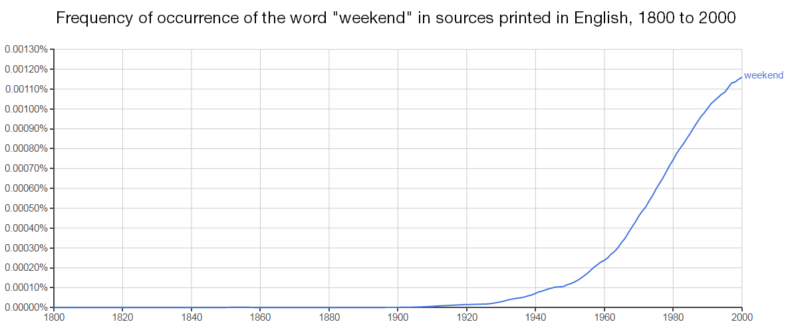

Many children had to contend with actual hunger rather than just bland diets, and child labor, often in dangerous conditions, was common. Child labor is not a practice unique to the Victorian era—however linked the two may be in the popular imagination.

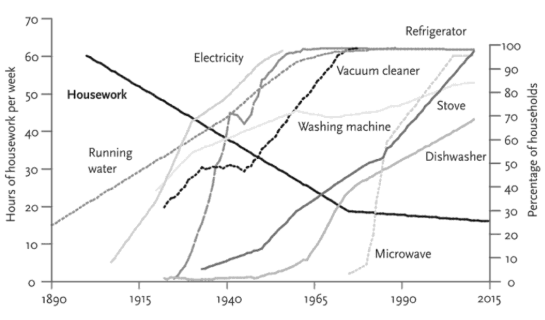

It had been ubiquitous since time immemorial and finally began to come under scrutiny during the Victorian age. As the wealth generated by industrialisation started to improve working conditions and wages began to rise, fewer and fewer children worked compared to the past.

None of this is to deny the existence of things worth worrying about today. But parents shouldn’t forget that their kids are growing up in a far safer and gentler world than they would have been just a few generations ago.

This first appeared in CapX.