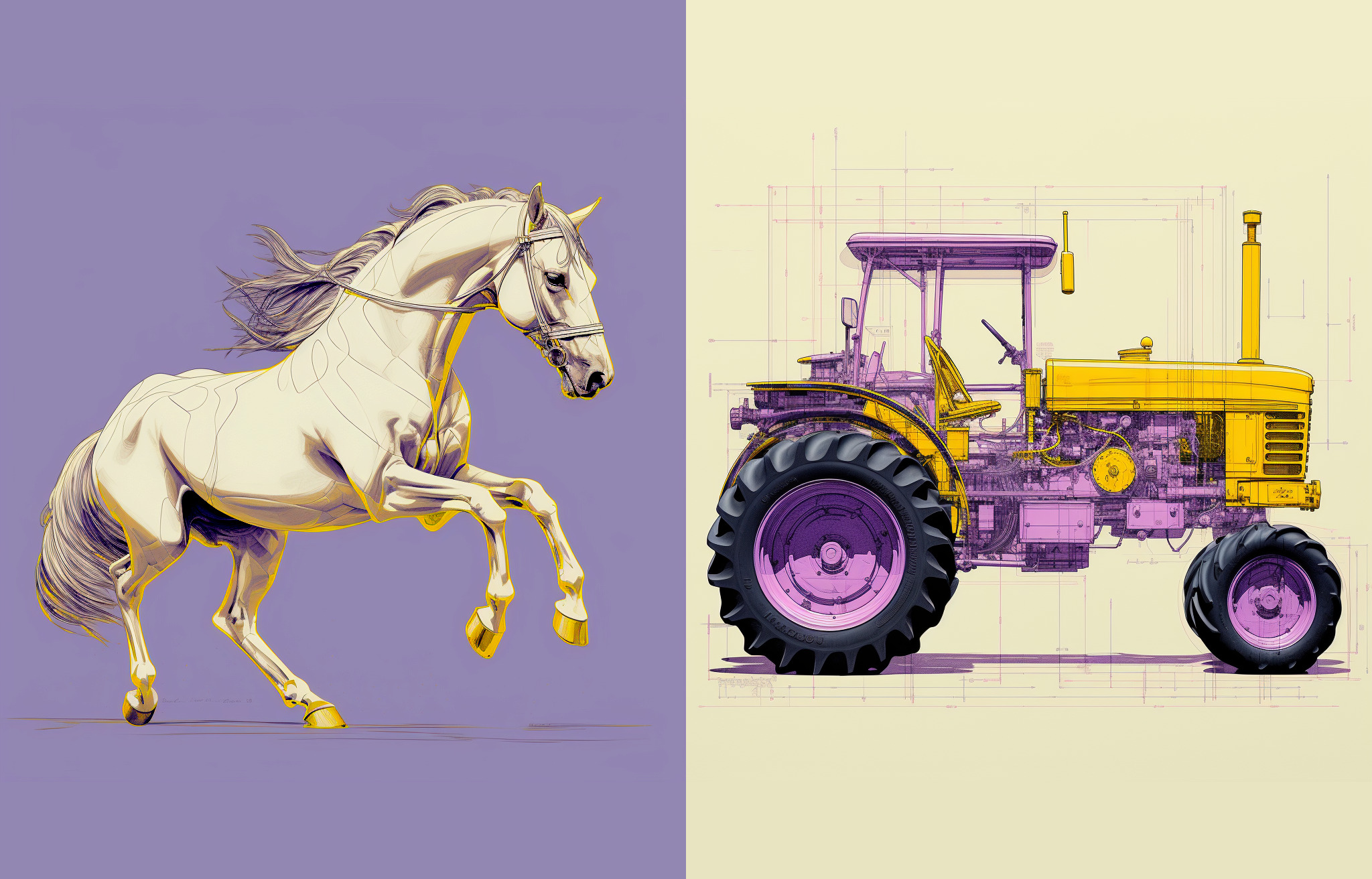

Summary: The proliferation of large language models, such as ChatGPT, raises concerns about job displacement, particularly in professions like writing and law. However, historical transitions, like the shift from horses to tractors, suggest that the adoption of new technologies is gradual, with human labor and machines coexisting and evolving together. While AI may revolutionize certain sectors, its widespread impact on employment is likely to be evolutionary rather than revolutionary.

“You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics,” wrote economist and Nobel laureate Robert Solow in a 1987 book review. While computing was making massive strides in the 1980s and ’90s—cumulating in the internet mania and dot-com bubble and its burst—it took a long time before we saw large, economy-wide impacts of this revolutionary general-purpose technology. Computers, internet, and (smart) screens have made the modern world unrecognizable from what it was just a few decades ago, but the process took a lot longer than most techno-optimists suggested then—and their followers are suggesting now.

Last year had a strong 1990s feel to it: 2023 became the year of AI worries, with ChatGPT and other large language models making a bid for disrupting all manner of industries. Writers, musicians, lawyers, editors, physicians, graphic designers, and more were some of the professions seemingly at risk of losing their livelihood to machines that quickly replicate their work at a fraction of the cost.

We should draw two conclusions from these large language models and past technological transitions: First, some of their features are truly remarkable and can very well compete with (some) lawyers, writers, musicians, or graphic designers over the next few years. Second, radical, labor-saving technologies are slow to diffuse across the economy, so these mainly middle-class professions are probably safe from mechanization and automation a while longer.

Take the iconic horses-to-tractor transition in agriculture over the 20th century. From invention and commercial availability, tractors took decades to overtake horses. The same was true for steam engines, that iconic energy invention powering the Industrial Revolution—which itself was both one of most radical and life-changing events in all of human history and pretty dull on account of its slow changes.

“Over the sweep of history the tractor has indeed had an immense impact on people’s lives,” The Economist said in December 2023, “but it conquered the world with a whimper, not a bang.” In all ages, tech innovations have defused across societies slowly: the old technology remains relevant for decades. Even in the 1930s, two to three decades after the first tractors were built, there was more equine than mechanical horsepower on American farms. Scholars usually put the cutoff point for when tractors overtook horses on farms after World War II, a generation or more after they were first employed.

The story in The Economist also highlights the connection to real wages and overall economy. Productivity and economic growth are a tide that lifts all boats. A rule of thumb is that labor-saving technology gets adopted only once it makes sense to replace labor with machines. That happens when the machines get good enough, the cost of running them falls sufficiently, or the alternative uses for labor get high enough.

For the first few decades of the tractor’s existence, they weren’t obviously better than the source of literal horsepower that preceded them. They were expensive to run, were not that powerful, and couldn’t do many things that a horse could. For one, they compelled farmers to purchase gasoline—a resource they didn’t have—rather than putting horses out to grazing on land or having children (or cheap labor) tend to the animals—resources that they did have. And during the Great Depression in America, cheap labor wasn’t that hard to come by.

In time, those trends reversed; real incomes and better-paid manufacturing jobs bid labor away from the farms, and the demographic transition to smaller families meant that children couldn’t be routinely relied upon to, for example, care for the animals. In economic speech, the optimal size of farms grew, and on these larger farms the now much better tractors came into their own right.

In contrast, the labor that large language models like ChatGPT purport to displace is often highly remunerated, while the costs of running the operations are pretty low, which suggest that artificial intelligence (AI) might displace some such workers.

Yann LeCun, chief AI scientist at Meta/Facebook, is less convinced. In an interview with Wired magazine’s Steven Levy, LeCun says that “chatbots can produce very fluent text with very good style. But they’re boring, and what they come up with can be completely false.” For Reason magazine last year, I reflected on the promise of ChatGPT along similar lines: “Bad writers, cheating students, lazy professors, and journalists echoing press releases have clearly met their match. But the more human, creative, authentic storytelling that is the center of all meaningful writing has not.”

The tractor attempted to compete directly with a farming industry routinely employing over a third of the labor force in the 1800s and early 1900s in the United States, constituting some 15 percent of gross domestic product. What is the total addressable market for large language models and by extension general AI? Statista estimates that the market size of AI in the United States, a $27 trillion economy, is some $100 billion—a fraction of a percent. Even if that grows seven-fold this decade in line with projections (nothing to scoff at!), that’s also not as revolutionary as most pundits have claimed in this the first year of their widespread adoption.

Solow, who died late in 2023, might have repeated his statement about this new form of the computer age. Like the computer in the 1990s, the onset of AI and large language models make more media puff and noise than they have real-world, real-economy impact.

There is some suggestion that adoption of new technology and consumer items happen somewhat faster today than, say, in the 1940s or 1980s, but not by a lot. Still, what is more likely to happen than mass white-collar unemployment is that we’re going to have a symbiosis for a while. The old human-labor technology and the new machines will coexist, and human workers will gradually employ the machines in different ways. An evolution, not a revolution.

At the end of the day, writes Mike Munger for the American Institute for Economic Research, ChatGPT is just a calculator. And like calculators did, it will obsolete some human labor. And that will be fine.