This article was published at the Pessimists Archive on 2/8/2024.

We cannot understand to what practical use a flying machine that is heavier than air can be put.

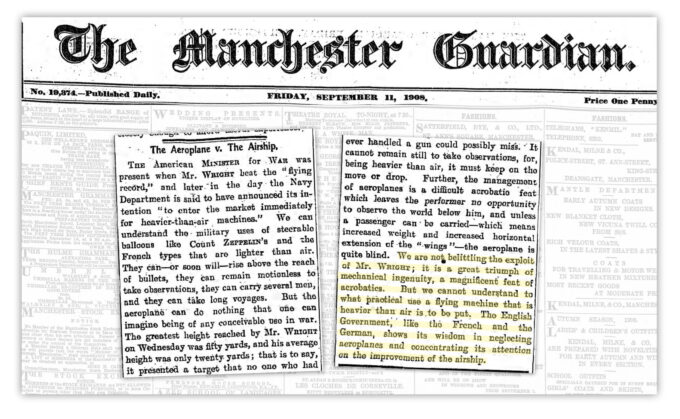

Manchester Guardian, 1908

This amusing quote was shared on Twitter by ex-Financial Times assistant editor Brian Groom. Naturally we went looking for the original source and after a little digging, we found it:

Revealed is the quote’s context: a comparison between aeroplanes and airships, prompted by a historic breakthrough: 1 week prior the Wright Brothers publicly proved possible heavier than air flying machines.

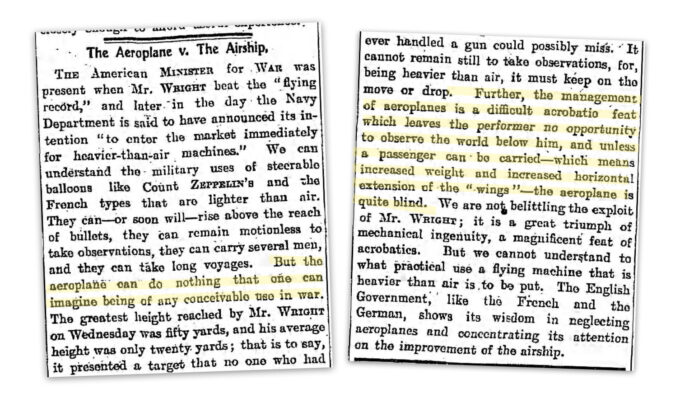

Sizing up the aeroplane against then dominant airships was a natural reaction to the breakthrough. Like many others, The Manchester Guardian (later renamed The Guardian) noted the existing limits of this nascent technology and the upsides of the established alternative.

Airships didn’t need a runway to take off or land, were easy to control, could hover mid-air and allowed the transport of many people at an average cruising altitude of 650ft – while the Wright Brothers only achieved 20ft. (The fact Airships were full of highly flammable gas went unmentioned.)

The Manchester Guardian commended the Wright Brother’s impressive “acrobatic” achievement and “great feat of mechanical engineering”, but dismissed the aeroplanes military potential because of early downsides: its low cruising altitude meant “it presented a target that no one who had ever handled a gun could possibly miss.” And its use in reconnaissance was doubted due to its limited capacity to carry passengers and the difficulty of piloting, giving “no opportunity to observe the world below.” The piece would end by commending the English, French and German governments for its focus on airship development.

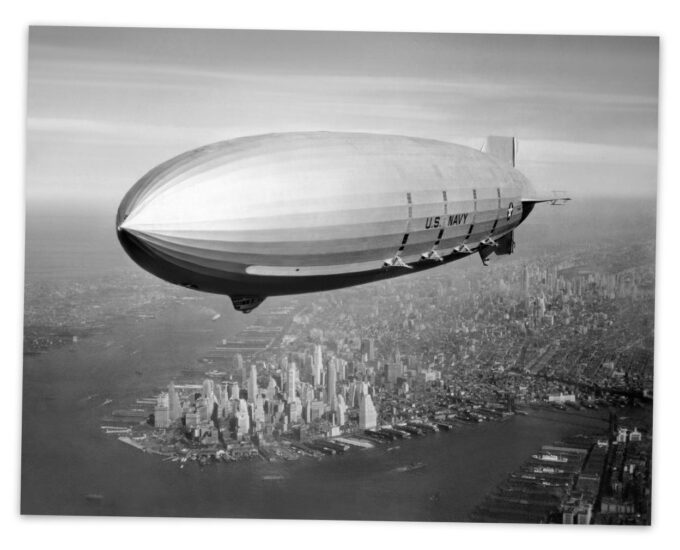

The US Military officials present at the Wrights public demonstration were more optimistic however – seeing beyond early limits – towards possible improvement, with the Navy signalling intent to begin purchase of the new technology immediately.

Only 6 years later World War I would begin, military Aeroplanes would take to the skies – first for reconnaissance – helping the allied forces prevent the German’s invasion of France, among other things. This new intelligence advantage, saw weaponization soon follow, as each side sought to take out each others reconnaissance crafts.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, France suggested it create a flying corps of 4,500 aeroplanes, the US set a goal of 22,625 – echoing the enthusiasm of its military leaders on first witnessing manned flight. It never managed to fulfil this goal and purchased the majority of its planes from France and the United Kingdom. By the end of the war it would form the Royal Airforce, the first dedicated airforce in the world, one that would play a key roll in World War II.

Beta Bias

On paper – looking at pros and cons – dismissing the aeroplane would have felt fair, convincing and well reasoned in 1908. The problem though: this could apply to many nascent breakthrough technologies when comparing them to established alternatives. It isn’t a fair or useful comparison.

This common error in thinking about technology is certainly a strain of “status quo bias,” but should probably have a name: we’re christening it “beta bias.”

Beta Bias: The inclination to compare an early-stage version of a new technology, typically in its beta or developmental phase, with a more developed and established alternative technology. This comparison often overlooks the growth potential, cost reductions and future improvements of the new technology, leading to an underestimation of its eventual impact and utility.

Every nascent innovation has a more developed predecessor, more familiar and socially acceptable, with clear advantages, and disadvantages that society has rationalized. We’ll be exploring ‘beta bias’ more in our next post.