Today marks the fifth installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org called Centers of Progress. Where does progress happen? The story of civilization is in many ways the story of the city. It is the city that has helped to create and define the modern world. This bi-weekly column will give a short overview of urban centers that were the sites of pivotal advances in culture, economics, politics, technology, etc.

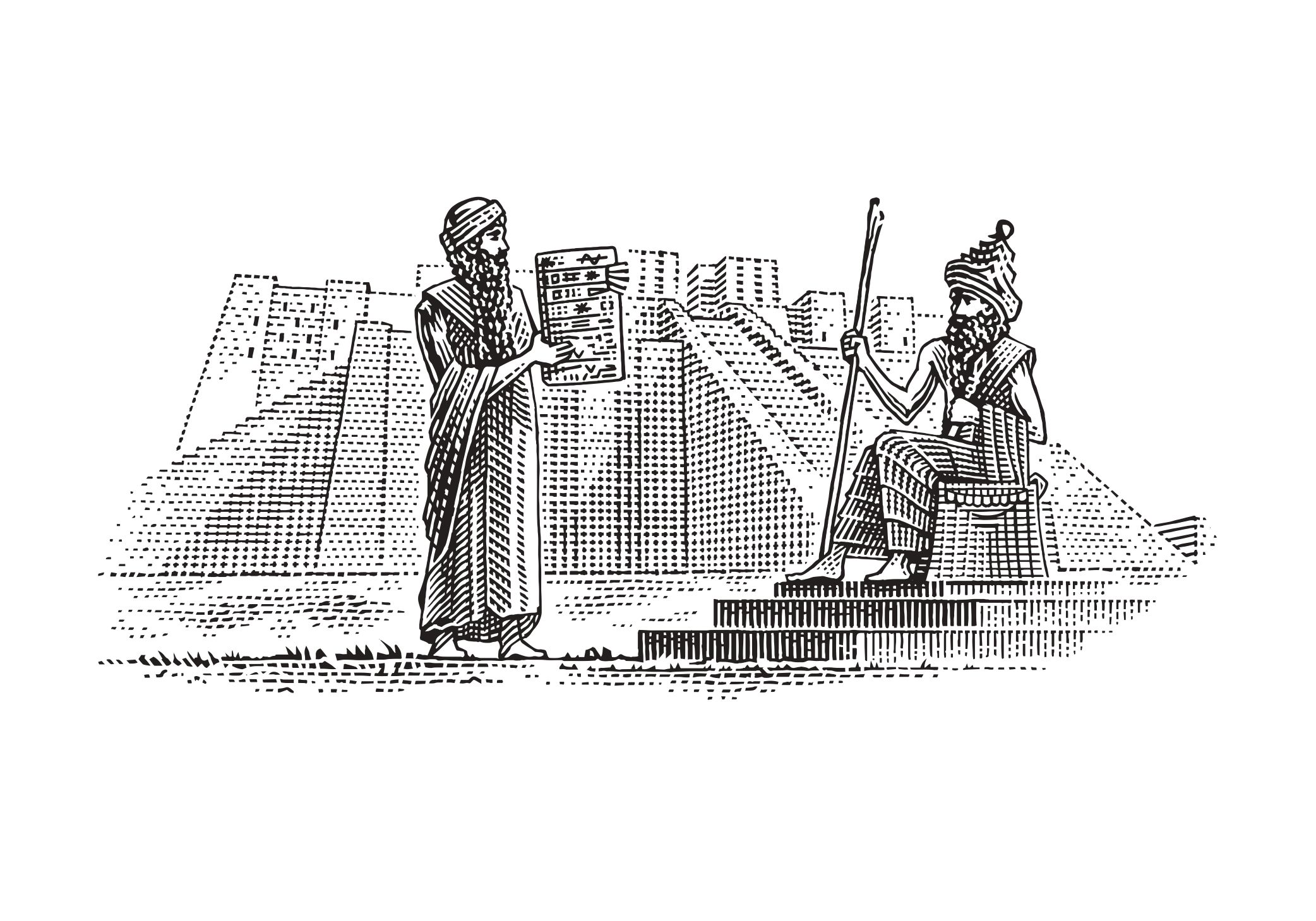

Our fifth Center of Progress is the Mesopotamian city of Ur during the so-called Sumerian Renaissance, in the 21st century BC. Ur then served as the capital city of a king named Ur-Nammu. Under his direction, the city issued the oldest surviving legal code in the world, the Code of Ur-Nammu, which predates the better-known Code of Hammurabi by three centuries. Ur-Nammu’s code of laws, which were carved onto terra cotta tablets and distributed throughout his kingdom, represented a significant breakthrough in the history of human civilization.

The Code of Ur-Nammu helped to establish the idea of a set punishment for a particular crime that applied equally to all free persons regardless of their wealth or status. In other words, the code replaced arbitrary standards of justice, which shifted with each new instance of a crime, with a uniform and transparent set of rules. Many of those rules were horrific by modern standards, but the code nonetheless represented a notable development toward what we now consider to be the rule of law.

References in ancient Sumerian poetry suggest the existence of an even older legal code than the Code of Ur-Nammu, called the Code of Urukagina, written in the 24th century BC. Unfortunately, the text of that earlier code has not survived. The Code of Ur-Nammu, as the oldest surviving legal code, is thus the best window that we have into the origins of lawmaking.

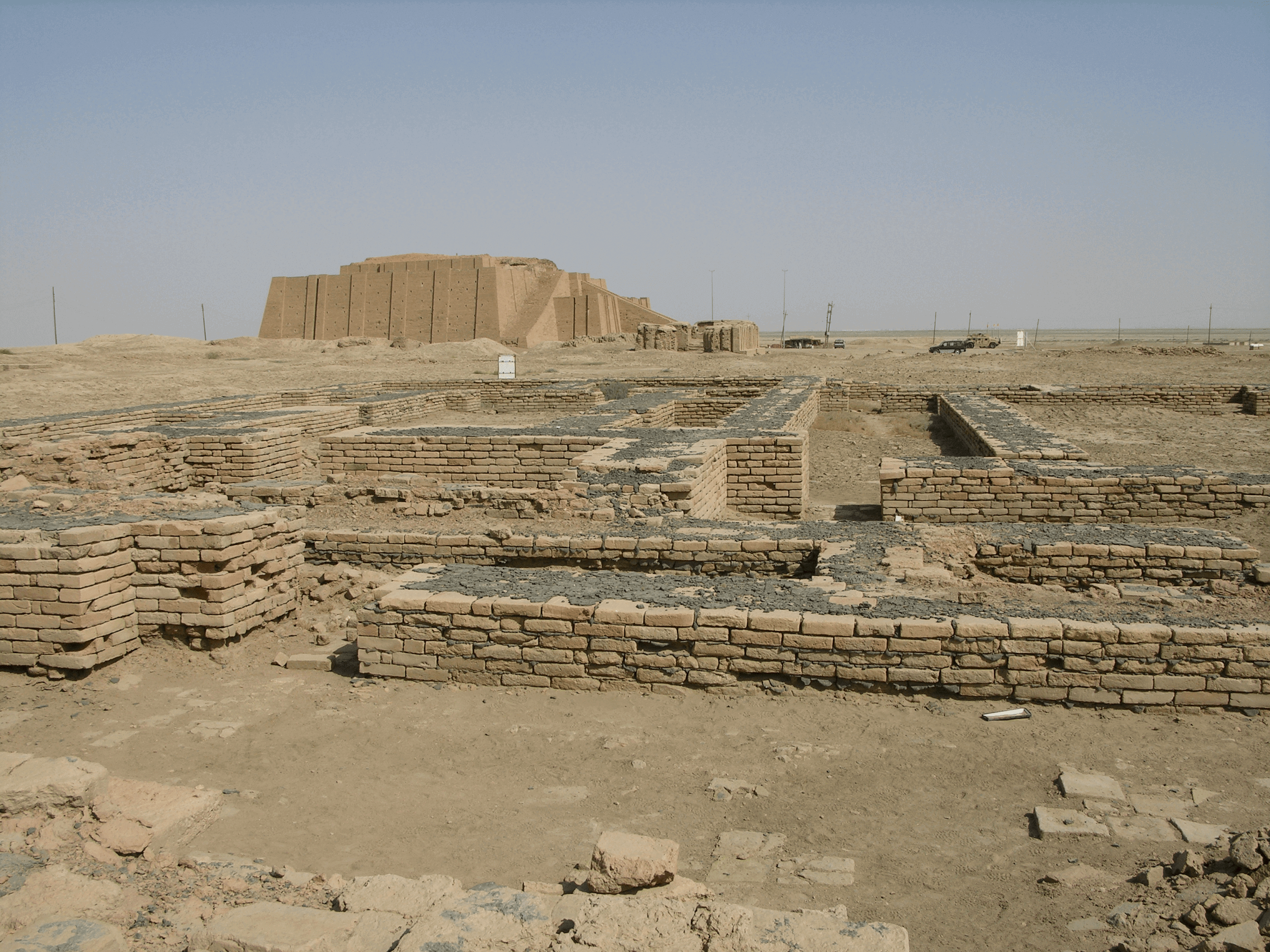

Today, the city of Ur lies in ruins in the desert of southern Iraq. Ur’s Great Ziggurat, erected to honor the Sumerian god of the moon, still stands. The Ur archeological site is also home to what may be the oldest still-standing arch in the world. Many of the artifacts found at Ur have been relocated and can now be seen in the British Museum in London and the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology in Philadelphia. Ur is part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site that also includes our 2nd Center of Progress, Uruk, which is less than 60 miles away.

During its golden age, Ur was the capital of a state holding together all of Babylonia and several territories to its east. It was also a key port of trade between Babylonia and regions to the south and east.

Picture the city, surrounded by palm trees and skillfully irrigated land, made fertile by tributary streams flowing to the river Euphrates that lay to the west. As you approached, you would have seen farmers tending barley fields, fishermen casting their nets into the streams, and herdsmen leading their sheep to graze.

As you entered the bustling urban center itself, you would have observed its many people. Ur’s population eventually swelled to 65,000. That may not seem like a lot—it is roughly the same as the modern-day population of Youngstown, Ohio or Schenectady, New York—but it was around 0.1 percent of the entire global population at the time. Ur would become the most populous city in the world and remain so until around 1980 BC.

The people of Ur wore skirts or wraps of kaunakes, a woolen fabric with a tufted pattern like overlapping leaves or petals. The rich wore belts of gold or silver, and wealthy women wore hair ornaments and jewelry of the same materials. Everyone, even royalty, went barefoot. Sandals would not appear in the region until centuries later. The city natives mainly had dark hair—the people of Sumer referred to themselves as the “black-headed ones.” The people of Ur likely shared the city streets with oxen pulling along wagons heaped with supplies, and the stench of manure may have been inescapable. The very wealthy traveled in chariots pulled by donkeys, or perhaps onager hybrids.

The city’s architecture featured columns, arches, vaults, and domes. You would perhaps have seen people carrying baskets filled with offerings on their heads walking toward one of the city’s temples to its numerous gods. The city’s temples were richly decorated with statues (often with blue lapis eyes), mosaics, and metal reliefs. The temple columns were sheathed with colorful mosaics or polished copper. Inscribed tablets lay at the temples’ foundations.

You would have seen the space where work had begun on a three-storied ziggurat of mud brick faced with burnt bricks set in bitumen. Upon that platform, a temple would soon be constructed. The temple would tower over the city and be visible from the far distance in the flat surrounding Mesopotamian countryside and honor the moon god Nanna, the patron deity of Ur. The partially reconstructed ziggurat stands today as the most prominent structure of Ur.

At the edge of the sacred precinct was the Royal Cemetery, out of use by that time for fifty-some years. There 2,000 people lay buried—royalty laid to rest wearing elaborate gold ornaments, alongside their attendants, victims of human sacrifice. But the city had abandoned that practice by the era that concerns us.

In the marketplace you would have seen artisans selling their wares such as woolen textiles, clothes and tapestries; jars, fluted bowls, and goblets, some made of precious metals; elaborate carved stone vessels of chlorite, bearing cuneiform inscriptions; ornaments and jewelry of semiprecious stones such as carnelian and precious metals; various tools and weapons. Passing through the food stalls you likely would have seen wheat, barley, lentils, beans, garlic, onions, and goat milk. You would have seen stone vessels of precious oils, and wine.

You might have paused at a stall selling carved musical instruments, stopping to admire a lyre featuring lapis lazuli—a stone all the way from the upper reaches of the Kokcha River in what is now Afghanistan, over a thousand miles away. Its presence a reminder of the city’s far-reaching trade.

Moving along, you might have observed two men hunched over a strategy board-game. The Game of Ur was then popular throughout Mesopotamia among people in every social strata. Perhaps you would have heard the players arguing about the rules, and then watched them turn to a clay tablet serving as a rulebook to resolve their dispute. (Such tablets, describing the game’s rules, have survived).

The people of Ur had a guide to help them navigate disputes concerning far larger matters as well. If you were to visit in the year that the locals called the “Year Ur-Nammu made justice in the land,” believed to be around 2045 BC, then you could have witnessed a history-altering moment. You would have perhaps had the good fortune to watch as Ur’s messengers disembarked from the city to deliver tablets bearing the new legal code throughout the kingdom.

The Code of Ur-Nammu, as the oldest surviving legal code, helped to redefine how people conceptualized justice. The Code of Ur-Nammu listed laws in a cause-and-effect format (i.e. “if this, then that”) that specifically outlined different crimes and their respective punishments. A total of thirty-two laws survive. (They can be read here).

The Code of Ur Nammu also introduced the concept of fines as a form of punishment—a notion we still rely on today. Fines ranged from minas and shekels of silver to kurs of barley. (The Sumerian measurement system is not fully understood, but a kur or gur was likely a unit based on the estimated weight that a donkey could carry).

Compared to the later Code of Hammurabi, the Code of Ur-Nammu was relatively progressive, often imposing fines rather than physical punishment on the transgressor. In other words, it often favored compensation for the crime’s victim over the enactment of retributive justice against the crime’s perpetrator. The Code of Hammurabi famously dictated that “If a man put out the eye of another man, his eye shall be put out.” That “an eye for an eye” rule is also cited in the Old Testament books of Exodus and Leviticus. In contrast, the older Code of Ur-Nammu states, “If a man knocks out the eye of another man, he shall [pay] half a mina of silver.”

In the prologue to the code, King Ur-Nammu boasted about his various accomplishments and claimed to have established “equity in the land.” By equity, he did not mean the modern concept of equality—after all, he ruled over a society with widespread slavery. But by establishing uniform punishments for crimes, he meant to ensure that both rich and poor free persons were treated equally before the law. In the prologue he noted, “I did not deliver the orphan to the rich. I did not deliver the widow to the mighty. I did not deliver the man with but one shekel to the man with one mina (i.e., 60 shekels). … I did not impose orders. I eliminated enmity, violence, and cries for justice. I established justice in the land.”

The king clearly saw his legal code as an important part of his legacy, and wanted to be remembered as a just ruler. The code certainly represented a step forward, when compared to a purely arbitrary system of punishment. It was arguably more humane than some legal codes that followed, such as the aforementioned Code of Hammurabi. That said, the Code of Ur-Nammu is not one that a modern person would want to live under. Some of the laws were ridiculous (“If a man is accused of sorcery he must undergo ordeal by water”), sexist (“If the wife of a man followed after another man and he slept with her, they shall slay that woman, but that male shall be set free”) or plain barbaric (“If a man’s slave-woman, comparing herself to her mistress, speaks insolently to her, her mouth shall be scoured with 1 quart of salt”).

Some of the laws were also confusingly specific, such as: “If someone severed the nose of another man with a copper knife, he must pay two-thirds of a mina [1.25 pounds] of silver.” Was there a different punishment if the knife used was not made of copper? (Today, if you’re curious, cutting off someone’s nose will land you in prison for one to twenty years—at least in Rhode Island, the only state I could find with a law that specifically mentions nose mutilation).

Today the city of Ur is perhaps best-known for being thought to be the birthplace of the Biblical patriarch Abraham. Abraham is an important figure in the religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, which are thus known as “the Abrahamic religions” for that commonality.

The advent of laws transformed how communities enact justice by ensuring a uniform and transparent set of rules. While many laws throughout history have proven to be mistakes, and unjust laws continue to pose serious problems in many countries, a system of laws is nonetheless better than a system where punishments are doled out without any consistency and at the whim of a ruler or a mob. By enacting the oldest surviving legal code, Sumerian Renaissance-era Ur has earned its place as our fifth Center of Progress.