An alien beamed down to Earth, especially to such bastions of global capitalism as London and New York, might be forgiven for thinking that we are in the midst of some sort of a catastrophe. Emerging from the New York Subway or London’s Tube, our inter-planetary traveller would have to make it past an army of charity workers raising money to house the homeless, save the children, feed the hungry, etc. “Why,” the visitor might wonder, “are so many Earthlings in need of help?”

Logic dictates that, as societies become richer, social spending should decline. Not so in the contemporary West, where social spending increases alongside rising incomes.

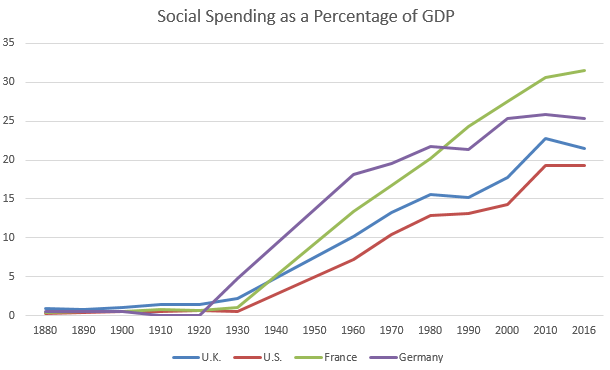

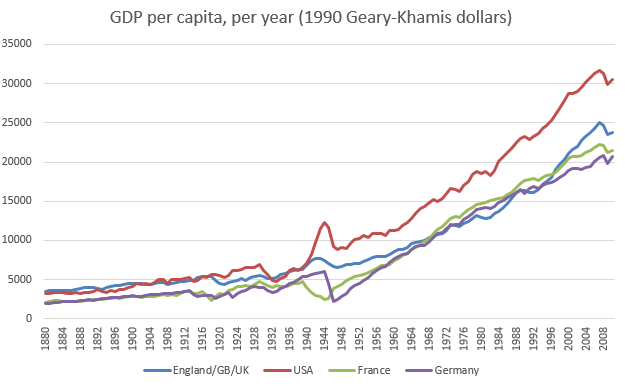

According to Peter H Lindert, Distinguished Professor of Economics at the University of California, Davis, social spending amounted to very little at the time when Western countries were, by modern standards, very poor. In his “Social Spending and Economic Growth since the Eighteenth Century”, Lindert found that social spending as a percentage of GDP in Great Britain, the United States, France and Germany, respectively, amounted to 0.86 per cent, 0.29 per cent, 0.46 per cent and 0.5 per cent in 1880. That year, GDP per capita in the above four countries came to $3,477, $3,184, $2,120 and $1,991 (all figures are in 1990 Geary-Khamis dollars as estimated by the Angus Maddison Project).

By 2010, incomes in the UK, US, France and Germany rose by 584 per cent, 858 per cent, 913 per cent and 938 per cent. What happened to social spending? Max Roser of Our World in Data updated Lindert’s figures and found that in our four countries, it rose by 2,549 per cent, 6,571 per cent, 6,566 per cent and 5,084 per cent respectively over the same time period. Except for Germany – which saw a tiny reduction in social spending between 1999 and 2016 – social spending as a share of the GDP is higher today than it was at the end of the last millennium. Strikingly, between 1880 and 2010, social spending rose, on average, 6.3 times faster than incomes.

Social expenditure comprises cash benefits, direct in-kind provision of goods and services, and tax breaks with social purposes. Benefits may be targeted at low-income households, the elderly, disabled, sick, unemployed, or young persons. Convention holds that civilised societies take care of those who cannot take care of themselves. That, however, is not the same as poverty alleviation – especially when poverty is as liberally defined as it is in the West today.

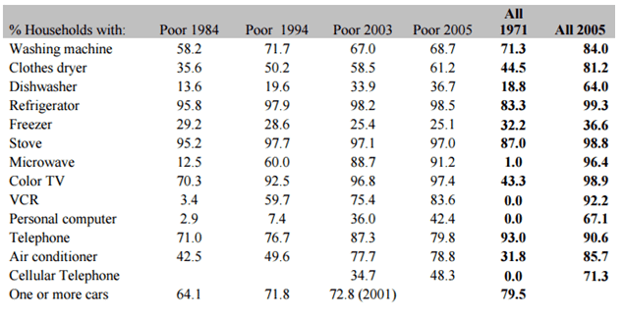

Consider what it means to be poor in today’s America. According to Steven G Horwitz, Professor of Economics at St Lawrence University, “poor US households are more likely to have basic appliances than the average household of the 1970s, and those appliances are of much higher quality”. In his 2014 paper “Inequality, Mobility, and Being Poor in America”, Horwitz found that in 1984, 83 per cent of all households in the United States owned a refrigerator. By 2005, 99 per cent of poor American households owned a refrigerator. Surely, similar trends can be observed in Great Britain, France and Germany.

Moreover, the skyrocketing rise in social expenditure is surely unsustainable and, under certain circumstances, harmful to both individuals and society at large. For one thing, not all our fellow citizens aspire to rise above the relative poverty levels as set, subjectively, in our nations’ capitals.

Take Jason Greenslate, the 28-year-old resident of San Diego, whom Fox News profiled in 2013. Video clips, which went viral, showed Greenslate buying sushi and lobster with a Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program debit card issued by the government. “Greenslate plays in a rock band and laughed at the idea of getting a normal job,” the report noted. “This is the way I want to live and I don’t really see anything changing,” Greenslate said. “It’s free food; it’s awesome,” he continued. Greenslate’s story is not typical, but it is difficult not to suspect that, on the margins, some have made similar life choices.

Some level of social spending, whether it is provided by government or by charities, is there to remain, but excessive generosity can be a disincentive to all those able-bodied men and women who see living off the state as a perfectly satisfactory way to survive. This state of affairs is bad for society, for it robs the nation of productive workers; it is bad for taxpayers, for it keeps their taxes artificially high; and it is bad for welfare recipients, for they cannot gain the kind of self-respect that only work can provide.

Each year, in almost all developed countries, average per capita incomes rise, thus alleviating the need for higher social expenditure. Our social spending should go down, not up!

This first appeared in CapX.