Summary: How far have women’s rights come in the last half-century? A new report by the World Bank reveals the remarkable progress and persistent challenges in achieving legal equality for women and girls in 190 countries. This article examines various aspects of women’s rights, such as their freedom to move, own property, start a business, and participate in politics, and makes the case that improving women’s rights benefits everyone economically and socially.

The World Bank recently released its latest “Women, Business and the Law” annual report that gathers some 50 years of data evaluating dozens of legal indicators regarding women’s rights in 190 countries. For each country, it answers questions such as “Can a woman choose where to live in the same way as a man?” and “Can a woman register a business in the same way as a man?”

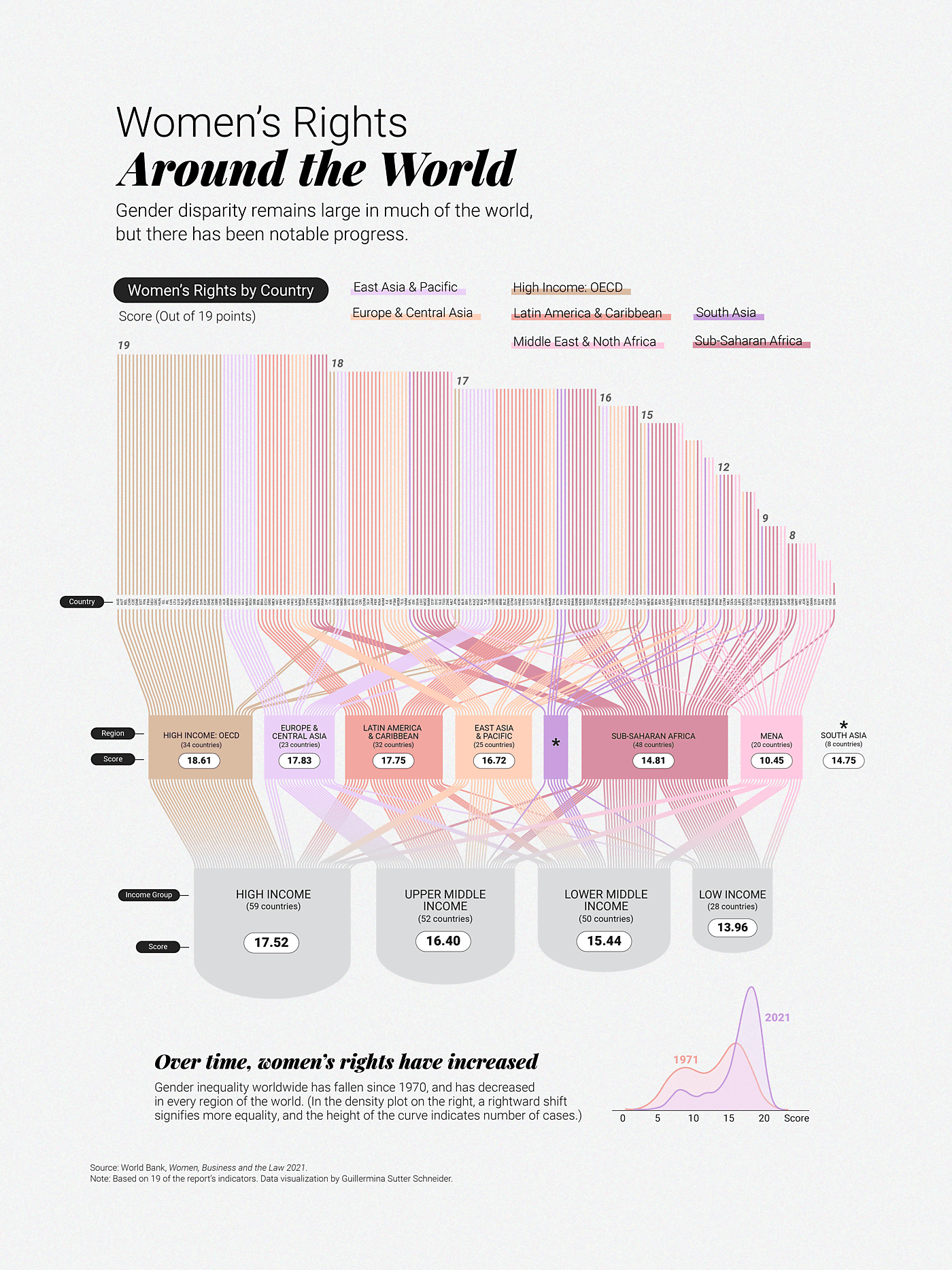

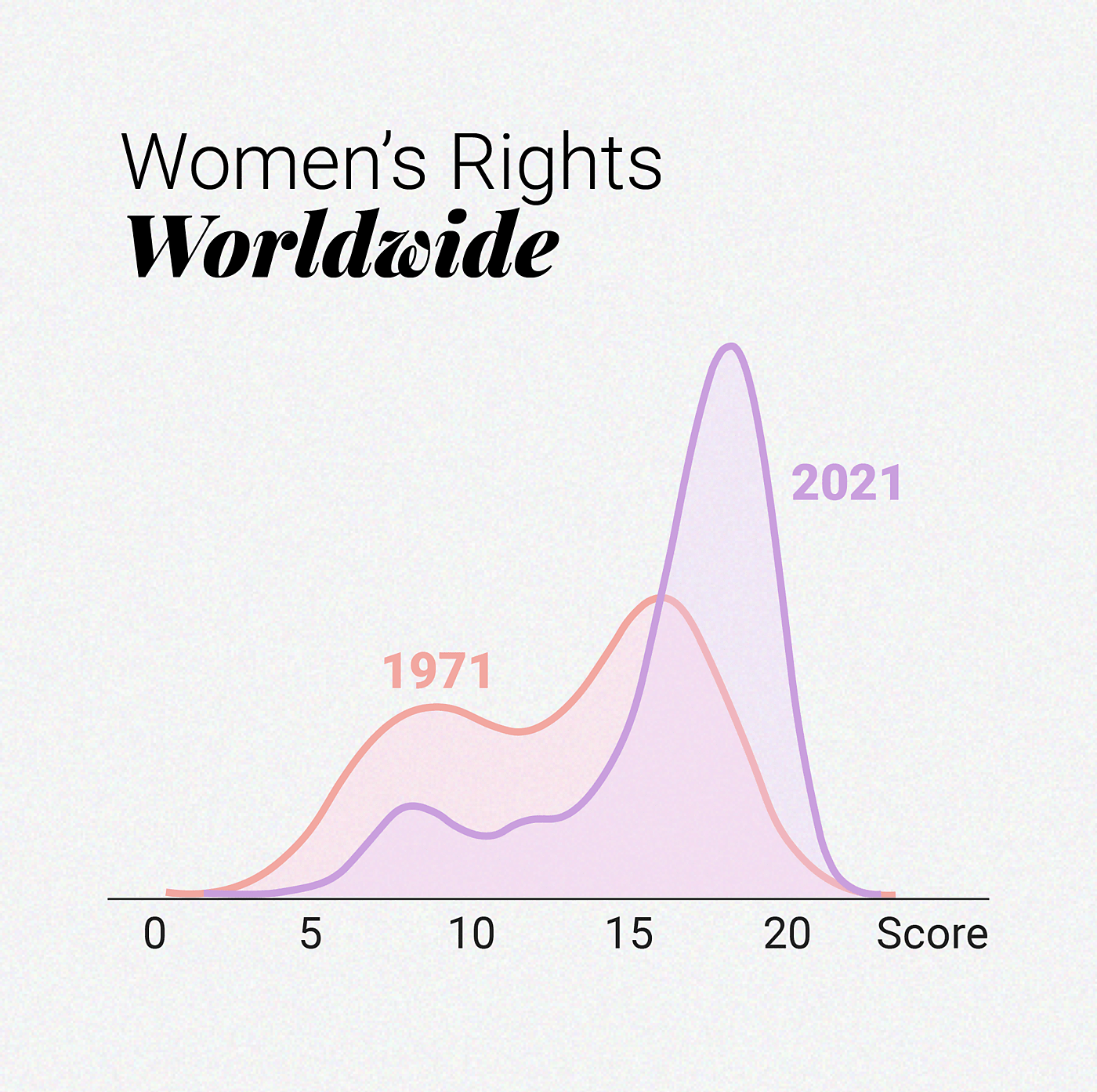

We looked at 19 of the report’s indicators that we felt best measured gender equality (we left out some indicators—e.g., on whether the government administers 100% of maternity leave benefits—that we thought were questionable or debatable). The data show that gender inequality worldwide has fallen significantly since 1970. (See the density plot below in which a rightward shift signifies more equality, and the height of the curve indicates number of cases.)

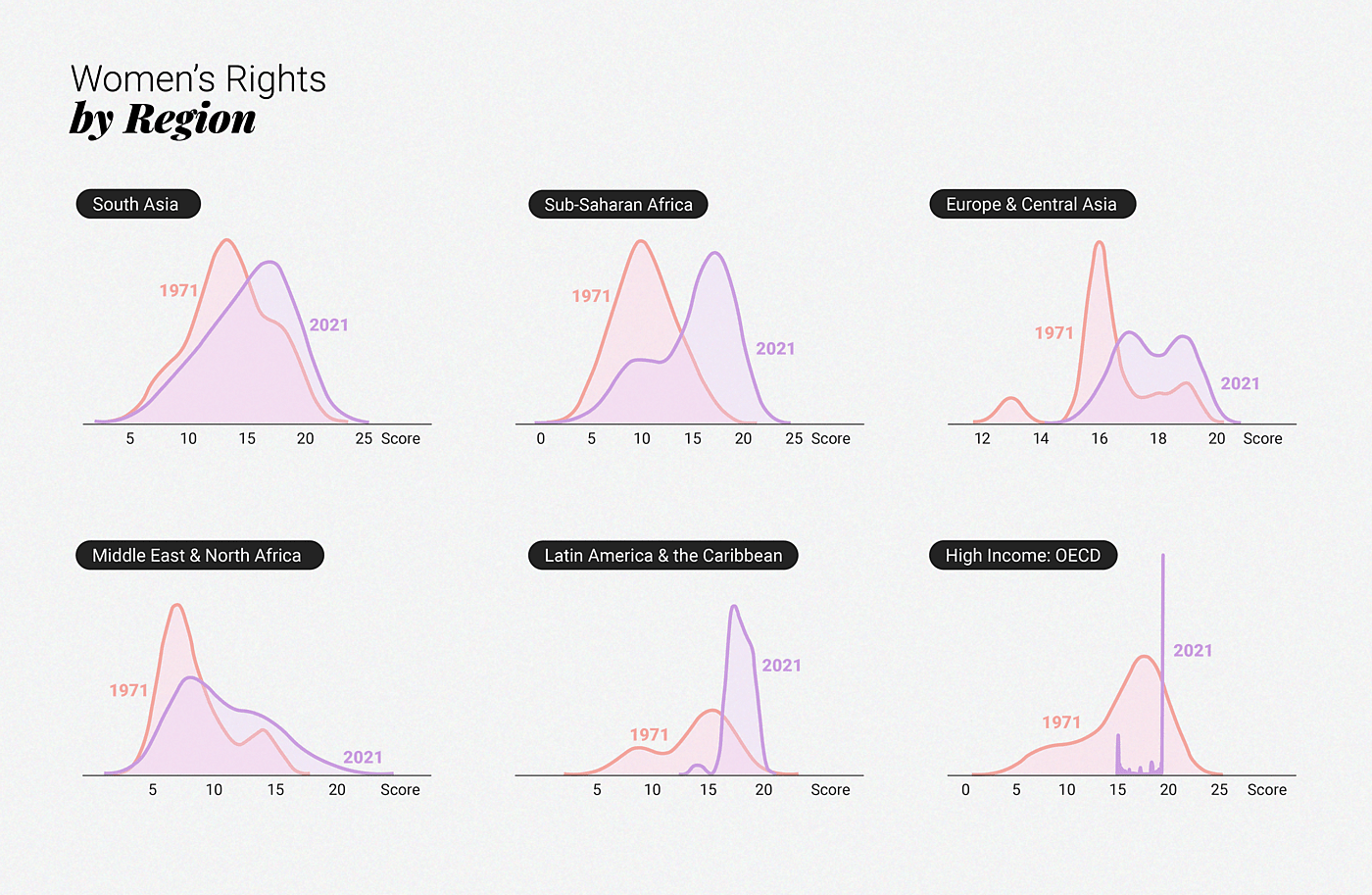

Moreover, every region in the world has seen declines in gender disparity with some—like sub‐Saharan Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean—experiencing notable improvements.

Rankings by region and country groupings (using the World Bank’s classifications) place high‐income countries as the most gender equal, and the Middle East and North Africa as the region with the greatest gender disparities. For a graphic overview of what we found, click on the preview below.

Despite the progress of the past half century, most of the world still has much to improve. For example, in terms of women’s mobility, the Middle East and North Africa is the region that has seen the most progress, but 65% of the region’s countries still limit women’s mobility compared to men’s, making the MENA region the world’s least equal by that measure. In the area of entrepreneurship, sub‐Saharan Africa is the most improved, and dramatically so, but 17% of the region’s countries still treat women unequally in that regard. Thirty percent of countries in the world restrict women’s property rights in some way.

The move toward greater equality of rights, important in and of itself, also tends to generate positive economic and social outcomes. For example, studies have found that improving certain economic rights, such as the freedom to open a bank account, leads to increases in labor supplied by women. Probably because they increase women’s ability to negotiate, property and inheritance rights for women are associated with improvements in female education and health, educational improvements in the next generation, and decreases in fertility rates. (See here and here, for example.)

Equality before the law and freedom are compatible, and indeed the former is an essential part of the rule of law which is itself a condition of freedom. But freedom and equal treatment before the law are not necessarily the same thing. A good example is Venezuela. The country gets the highest ratings on gender equity according to the World Bank, but Venezuela is also among the least free countries in the world. There can be little doubt that in a much freer country like Uruguay, which ranks a bit below Venezuela on gender equality, women enjoy greater opportunities, well‐being, and better treatment under the law in general than they do in Venezuela.

Nonetheless, studies show that the greater the level of economic freedom, the more likely it is that men and women will receive equal legal treatment. To most benefit women, the promotion of equal rights between the sexes should go hand in hand with the promotion of high levels of overall freedom.

(For a closer look at the data and how we compiled it, see here.)

This post also appeared in Cato at Liberty.