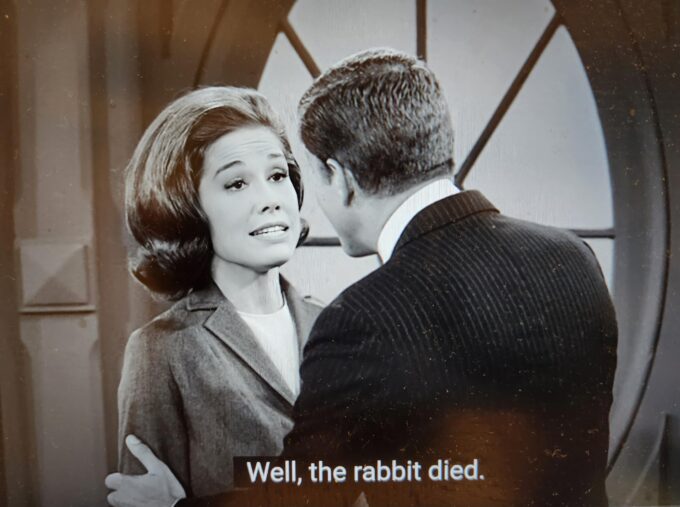

A 1962 episode of the sitcom the Dick Van Dyke Show centers around a couple struggling to decide what to name their first child. Much of the comedy remains accessible to a modern audience. But one part of the episode that is confusing to a modern viewer occurs toward the beginning, when actress Mary Tyler Moore’s character conveys to Dick Van Dyke’s character, her husband, that she is pregnant. A shortened version of the scene’s script follows.

Her: “I just came from the doctor.”

Him: “Doctor? What happened?”

Her: “Well, I drove down this morning . . .”

Him: “What, in the car? Alone? On the highway? You smashed into somebody. You’ve had an accident. [. . .] Anyway, you’re alright? Nobody was hurt?”

Her: “Well, the rabbit died.”

Him: “Are—you—oh my gosh.”

The husband immediately recognized the meaning of the cryptic (to modern ears) words “the rabbit died” and knew that his wife was pregnant. A person today might assume that this must be some kind of secret code that the couple decided on in advance. But just about everyone in the United States in the 1960s would have understood those three words—“the rabbit died”—to indicate pregnancy. It was a common saying at the time. And the phrase’s origins are rather gruesome.

Once, taking a pregnancy test literally involved sacrificing the lives of rabbits. These days, at-home over-the-counter pregnancy tests available at any drugstore require the sacrifice of nothing more than a small disposable object made of plastic that detects the presence of the pregnancy hormone, hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). But before the invention of these devices, the typical way to test for hCG entailed injecting a live female rabbit with a woman’s urine, waiting a few days, killing the rabbit, dissecting the rabbit, and examining the rabbit’s ovaries. If the slain rabbit’s ovaries were enlarged, indicating exposure to the pregnancy hormone, then the test result was positive. If the deceased rabbit’s ovaries were a normal size, then the test result was negative.

While grisly, the rabbit test, which was also sometimes enacted on mice instead of rabbits, was effective—perhaps even 98 percent accurate. It was the first highly accurate method of detecting pregnancy put into widespread use. As his New York Times obituary notes, the inventor of the so-called rabbit test, Dr. Maurice Friedman, even quipped, “The only more reliable test is to wait nine months.” Today’s at-home pregnancy tests are about 99 percent accurate, require no visit to a doctor’s office, and produce results within minutes rather than days. And pregnancy tests today of course no longer require the killing of any fuzzy, long-eared, hopping creatures. Such simple at-home tests were first marketed in the 1960s and widely adopted in the 1970s, as the greater convenience they offered helped them to rapidly replace the rabbit test.

The rabbit test came into use in the 1930s and continued to be used regularly in the early 1960s and occasionally even later. The test was still familiar to the public when, in 1978, an episode of the TV series M*A*S*H depicted the surgeon character Hawkeye performing an ovary surgery on a pet rabbit (without killing it) to learn whether the character Margaret was pregnant.

When Mary Tyler Moore’s character said in 1962 that “the rabbit died,” the audience would have understood her words to be literal: her doctor had likely informed her that she was pregnant based on the results of a test that involved killing and taking apart a rabbit. Because, of course, women did not typically kill and dissect the rabbits themselves. They left a urine sample with a doctor, who would send the sample to a laboratory where the ill-fated rabbits awaited injection, death, and dissection. Then the doctor would inform the patient of the pregnancy test results.

Public confusion regarding how exactly the so-called rabbit test worked led to the widespread misapprehension that the rabbits involved only died if the test result was positive and otherwise survived (like the fortunate fictional rabbit on M*A*S*H). In reality, each test entailed a rabbit’s death, regardless of whether the test result proved positive or negative. But the phrase “the rabbit died” soon became a common euphemism for announcing pregnancy. Even doctors would often notify patients of a positive result by saying “the rabbit died,” although doctors presumably had a better understanding of how the test functioned than did the general public and knew that the rabbit died either way.

According to Washington Post history writer Gillian Brockell, the rabbit test resulted in the killing of at least “tens of thousands of rabbits.” Going down the rabbit hole of history reveals many routine cruelties now thankfully left behind—often rendered obsolete by scientific advances offering more humane alternatives, as in the case of the rabbit test.