Earlier this month, I wrote about the determined efforts of socialists on both sides of the Atlantic to conflate capitalism with racism. No doubt, some promoters of capitalism were racists. But that is hardly surprising, since racism, along with slavery and wanton cruelty, were universal and, until recently, eternal phenomena.

The truth is, no culture in documented history comes close to the high standards of civilised behaviour that we expect from one another in the contemporary, which is to say democratic and capitalist, West. What I objected to in my column was the implicit notion that socialism was, somehow, less racist. And, as I showed by looking at the history of socialism, the opposite comes closer to the truth.

Yet Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s noble savage – a mythological creature living in harmony with nature and fellow beings – maintains a stronghold on socialist imagination. Consider the recent articles in The New York Times titled, The Climate Crisis? It’s Capitalism, Stupid, and Lenin’s Eco-Warriors. In the first, Benjamin Y Fong recommends democratic socialism as a solution to global environmental problems, while in the second, Fred Strebeigh praises Lenin as “a longtime enthusiast for hiking and camping” who turned Russia into “a global pioneer in conservation”.

Before delving deeper into The Times’ peculiar take on the environmental legacy of socialism, a little bit of background is in order.

This year marks 100 years since the Bolshevik putsch in Russia – an event that unleashed upon the world the most destructive ideology ever conceived by the human mind. The Times, which is the main source of news for progressive intelligentsia in the United States, has chosen to commemorate the cataclysmic events of 1917 in a series of sympathetic (and much-ridiculed) articles with titles such as, When Communism Inspired Americans, Thanks to Mom, the Marxist Revolutionary, Make It So: Star Trek and Its Debt to Revolutionary Socialism, and Why Women Had Better Sex Under Socialism.

Recall that The Times was complicit in whitewashing the crimes perpetrated by communist regimes for close to century, beginning with the discredited reportage of Walter Duranty – an Anglo-American correspondent who famously described concerns over man-made famine in Ukraine as “malignant propaganda”. Duranty’s crime against journalistic standards of truth-telling (from 1932 to 1934, the Holodomor claimed between 2.4 and 7.5 million lives), earned him a Pulitzer Prize – a high honour that The Times has repeatedly refused to relinquish.

But, let’s return to the newspaper’s recipes for saving the planet. According to the writers in The Times, capitalism is destroying the planet, while socialism (both in its original Leninist form and in its “democratic” form that is currently advocated by the US Senator Bernie Sanders) could save it. As Fong writes:

“The real culprit of the climate crisis is not any particular form of consumption, production or regulation but rather the very way in which we globally produce, which is for profit rather than for sustainability. So long as this order is in place, the crisis will continue and, given its progressive nature, worsen. This is a hard fact to confront. But averting our eyes from a seemingly intractable problem does not make it any less a problem. It should be stated plainly: It’s capitalism that is at fault…

“We have a much better chance of making it past the 22nd century if environmental regulations are designed by a team of people with no formal education in a democratic socialist society than we do if they are made by a team of the most esteemed scientific luminaries in a capitalist society. The intelligence of the brightest people around is no match for the rampant stupidity of capitalism….

“On the defensive for centuries, socialists have become quite adept at responding to objections from people for whom the basic functions of life seem difficult to reproduce without the motive power of capital. There are real issues here, issues that point to the opacity of sociability, as Bini Adamczak’s recent book, ‘Communism for Kids’, playfully explores. But the burden of justification should not fall on the shoulders of those putting forward an alternative. For anyone who has really thought about the climate crisis, it is capitalism, and not its transcendence, that is in need of justification.”

Bini Adamczak’s “playful” Communism for Kids aside, I think it is possible to answer most of Fong’s concerns by looking at the actual environmental records of socialist and capitalist economies.

To start with, all forms of production result in some environmental damage. Agricultural production clears forests, displaces wildlife and destroys the biosphere. Industrial production spews harmful gases into the atmosphere and releases pollutants into rivers. Even the service sector pollutes, given its reliance on electricity and the concomitant CO2 emissions. So the real question is not which economic system is the perfect steward of the environment, but which economic system is the better steward.

When answering that question, the following concepts should be kept in mind: economic efficiency, tragedy of the commons and the environmental Kuznets curve.

Socialist economies were very inefficient. (That’s still the case in the surviving ones in Cuba, Venezuela and North Korea.) To compensate for the inefficiency of central planning, which emanated from the lack of a market-based price mechanism, socialist economies generally ignored environmental damage and other negative externalities. To maximise production (in order to try to keep pace with the much more efficient capitalist economies), socialist countries had low, or non-existent, emission standards. Health and safety regulations were either ignored or lacking altogether. Socialist economies also banned independent trade unions and, often, resorted to slave labour.

The socialists’ disregard for the environment was further exacerbated by their contempt for property rights. In capitalist economies, farms and factories are owned by individual people or corporations. If they cause damage to the environment or the workforce, they can be held accountable in the court of law. In socialist economies, land and air (and, in the most extreme cases, people) were owned by the state and suffered from the “tragedy of the commons”.

A state-owned factory tasked by the central planners with producing a certain quantity of iron bars, for example, was not only allowed, but actively urged, to meet its production quota irrespective of the damage caused to the environment and to the populace. In capitalist economies, the state is entrusted with enforcing environmental standards and protection of workers. In socialist economies, the state is both the enforcer of production quotas, and the supposed protector of the environment and the workers. When it came to choosing between the two, the socialists almost invariably chose the former: they cut corners in order to compensate for the inefficiency of central planning.

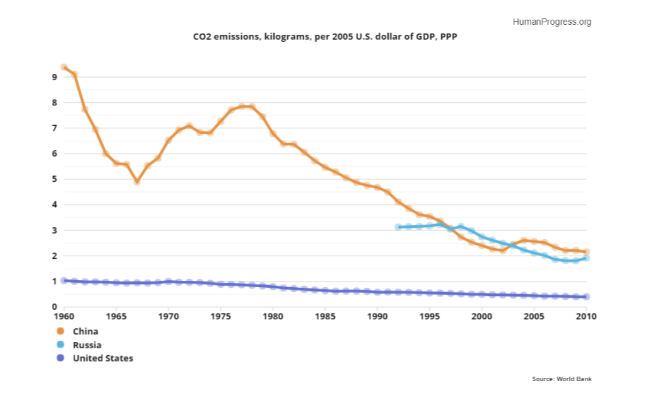

That problem is clearly illustrated by the comparison of the amount of CO2 emissions per dollar of output in socialist and capitalist countries. Note that, over time, emissions declined in the United States from already low levels. A similar trend can be observed in Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 (regrettably, I do not have data for the USSR prior to 1991).

Perhaps the best example of socialist disregard for the environment can be seen in data for China. Emissions during Mao Zedong’s Great leap Forward (1958-1962) were, compared to the United States, stratospheric. They declined afterwards, but remained very high until the late 1970s, when China abandoned socialism. Since China started liberalising its economy (by introducing the price mechanism and property rights), its emissions drastically declined.

Last but not least, socialist countries were, in large part as a result of central planning, much poorer than their capitalist counterparts. That is important, because of a phenomenon known as the environmental Kuznets curve. As a general rule, the richer the people are, the more likely they are to pay for “luxury goods”, such as clean air and rivers, as well as high health and safety standards in the workplace. It may sound strange to the modern ear, but clean environment and happy labour force are, in a very real sense, “luxuries” that were unavailable to our much poorer ancestors.

Really poor people, such as those in large parts of Africa and Asia, are primarily concerned with their survival. All other considerations are secondary. Don’t believe me? Following the collapse of the Zimbabwean economy, people started slaughtering the previously protected wildlife in order to feed their families. Following the collapse of the Venezuelan economy, animals from the zoo in the nation’s capital found themselves on the menu. During the Holodomor in Ukraine, people ate one another. My point here is not to denigrate environmental concerns, but to point to the real trade-offs that poor people in dysfunctional socialist economies have to face on daily basis.

Socialism, then, is not the answer. Historically speaking, environmental damage emanating from socialist production was vastly greater than environmental damage emanating from capitalist production. All and I repeat all academic studies done in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet empire found the quality of the environment in the formerly socialist countries to be inferior to those in capitalist countries.

The best way to protect the environment is to get rich. That way, there is enough money not only to meet the needs of ordinary people, but also to pay for cleaner power plants and better water-treatment facilities. Since capitalism is the best way to create wealth, humanity should stick with it.

This first appeared in CapX.