On a cliff overlooking the upper Mississippi River in Wyalusing State Park, Wisconsin, stands a peculiar monument: a dedication to a pigeon.

The Passenger Pigeon was a once-plentiful bird that flew over the skies of North America. Surviving records show that billions of birds swarmed together during the breeding season, allegedly blackening out the sun for days on end and forcing people to take cover from the literal storm of excrement from the skies. The largest gathering ever recorded was in 1871 in Wisconsin, with hundreds of millions of birds nesting over an area the size of roughly thirty Manhattans.

Forty years later, the bird was extinct. The plaque on the Wyalusing monument comes with a particularly condemnatory line, penned by conservationist Aldo Leopold: “This species became extinct through the avarice and the thoughtlessness of man.” On the centenary of the death of the last passenger pigeon, ornithologists and conservationists banded together in the Project Passenger Pigeon to lament the loss of the species and sound the alarm for other species facing extinction.

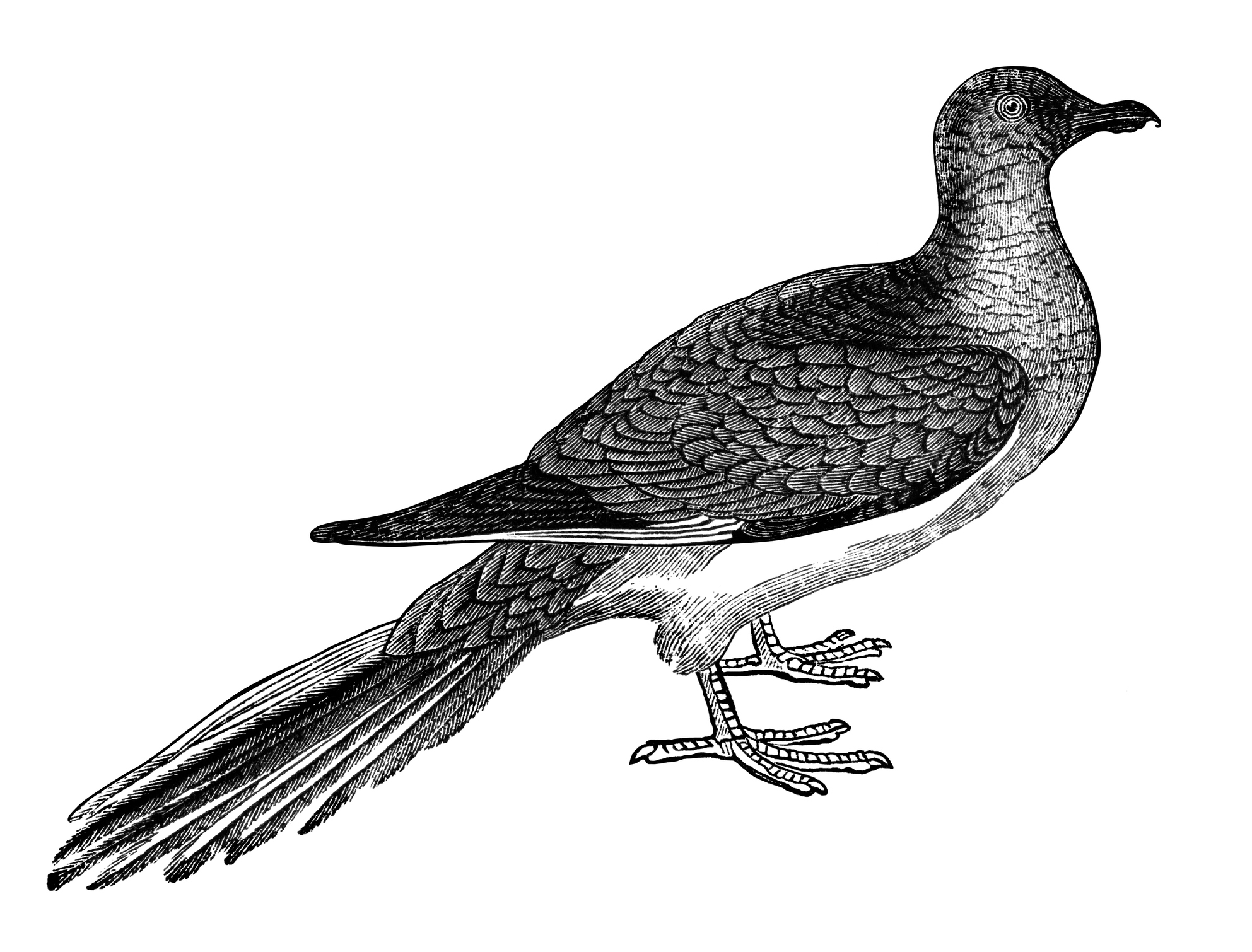

The tragedy of the Passenger Pigeon is an environmentalist staple. The pigeon was an “emblem of bounty” provided by nature – but its downfall, alleges the science author and journalist Charles Mann, was the result of man’s “squandering of that bounty.” The Passenger Pigeon makes for a good story: a colorful bird, previously existing in unheard-of abundance, fell prey to profit-seeking colonialists, their dirty industries and disregard for nature.

This story is mistaken – or at least incomplete.

Most of the observations of the Passenger Pigeon go back no more than a few centuries. They were accompanied by the typical colonialist awe for the widespread virgin soil and the vast natural emptiness of the land that the latter felt destined to conquer. The colonialists’ mistake, repeated and multiplied by ecologists until this day, was to believe that the pre-Columbian North America was always like that: a place of pristine, uninhabited forests, filled to the brim with game and natural bounty.

As ignorance about native societies gives way to more sophisticated view of the past, many beliefs about pre-Columbian North America have to be updated – including, it seems, the story of the Passenger Pigeon. The extreme state of abundance, in which generations past encountered the pigeon, ought to have sounded alarm bells: How come that they did not have more predators? Could this abundance really be part of a natural ecosystem?

In fact, the peculiar wilderness that confronted colonialists shows all the hallmarks of an ecosystem in sudden disarray. The “outbreak populations,” such as that of the passenger pigeon, is what happens when keystone species are abruptly removed from the environment. Contrary to what nineteenth century ornithologists thought, the Passenger Pigeon had not been swarming in the billions before the Europeans arrived. Its bones are almost entirely absent from the native peoples’ archaeological sites. The simplest explanation, argued the late geo-archeologist William Woods, is that Passenger Pigeons were actually quite rare in North America before Columbus.

Feeding on acorns, nuts and grains, the pigeons were ecological competitors of the human population, which survived by hunting, agriculture and forestry. When the native population succumbed to the European “germs and steel,” former’s “close, continual oversight” of the land disappeared. After “epidemics removed the boss,” writes Mann, “ecosystems shook and sloshed like a cup of tea in an earthquake.” The passenger pigeon “burst and blasted, freed from constraints by the disappearance of Native Americans.”

Rather than merely adapting to the environment around them, Native Americans of centuries past transformed nature to suit their needs. In contrast to the story of an industrial man recklessly hunting a species to extinction, the passenger pigeon is a lesson in the dynamics of ecological systems. When the apex predator, who burned the forest and consumed its food, suddenly disappeared, a previously peripheral species saw an initial and unsustainable boom in their numbers. The European writers mistook an ecosystem in disarray for an abundant natural treasure.

While it is true that nineteenth century Americans hunted the passenger pigeon, plowed the land where the bird flourished and deforested the woods where it lived, the natural abundance of North America for which the pigeon has become a synonym is a myth – a figment of rousseauian imagination. The pigeon was rare in pre-Columbian North America, because it competed with native tribes for food and space. While extinction of the Passenger Pigeon was a tragedy, it represented but a return of the land to human management.