In 2015, David Cameron’s government enshrined in law the UK’s commitment to spend 0.7 per cent of its gross national income on foreign aid each year. Ahead of last month’s general election, Theresa May reaffirmed Cameron’s commitment, which amounted to over 13 billion pounds in 2016. “Let’s be clear,” May said, “the 0.7 per cent commitment remains and will remain.”

British charities, including Save the Children, Oxfam, Christian Aid and Comic Relief, praised Mrs. May’s decision, stating that “the aid should be untied, focused on poverty reduction and spent through an independent Department for International Development.” Yet many of the same organizations are also concerned about what they perceive as the lack of government spending at home.

“Grenfell Tower is a Hurricane Katrina moment, revealing the shameful state of Britain,” wrote Oxfam’s strategic adviser Duncan Green following the Grenfell Tower fire. “Austerity, which has seen the budgets of local government cut dramatically with the greatest cuts felt by the poorest areas,” was partly to blame for the disaster, he averred.

While the continued plight of the world’s poor and problems experienced by the British underclass should not occasion jokes about “magic money trees”, it is a simple fact of life that the UK, like most Western nations, must economize. The British debt and deficit amount to 86 per cent and 2.6 per cent of GDP, and while UK domestic spending is best left to British economists to address, I would like to offer some thoughts on foreign aid. And, in particular, the theory behind foreign aid and its impact on the world’s poorest region, Africa.

The first question is whether aid is necessary. In the 1950s and 1960s, many development economists believed in the “vicious cycle of poverty” theory, which argued that poverty in the developing world prevented the accumulation of domestic savings. People in poor countries consumed all of their income and had nothing left to save and invest. Low savings resulted in low domestic investment, and low investment was seen as the main impediment to rapid economic growth. Foreign aid, therefore, was intended to fill the apparent gap between insufficient savings and the requisite investment in the economy.

Today’s calls for more foreign aid are often based on the same theory. Thus, the UK’s Department for International Development (DfID) website claims that it is “targeting British international development policy on economic growth and wealth creation [in poor countries].” The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) promises to work “with private-sector companies to spur economic development, so that citizens can participate in a vibrant economy that allocates resources wisely.”

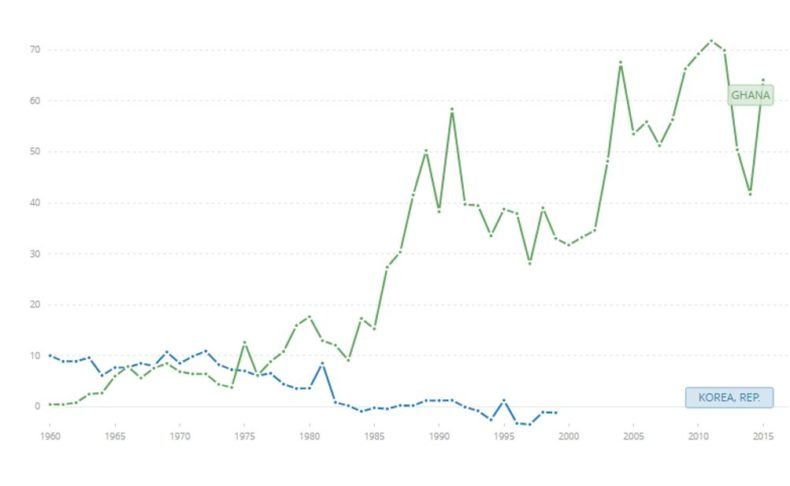

Yet experience contradicts the “vicious cycle of poverty” theory. Today, many formerly poor countries enjoy high standards of living, while others have stagnated or, in some cases, regressed. For example, the 1960 per-capita income in South Korea was $1,102. In Ghana it was $1,053. By 2015 Korea had reached $25,022, while Ghana is yet to break $2,000, only rising to $1,696 (the figures are in 2010 dollars). Yet, as can be seen in the graph below, Ghana received much more in net official development aid (ODA) per capita than South Korea between 1960 and 2015 (figures are in current U.S. dollars).

As New York University Professor William Easterly wrote, “It doesn’t help the poverty trap story that 11 out of the 28 poorest countries in 1985 had not been in the poorest fifth back in 1950. They had gotten into poverty by declining from above, rather than being stuck in it from below, while others escaped. If the identity of who is in the poverty trap keeps changing, it must not be much of a trap.”

Countries that improve their policies and institutions — by increasing their trade openness, limiting state intervention in the economy, building a business-friendly environment, and emphasizing protection of property rights and the rule of law — tend to grow faster than others. Such countries also tend to attract foreign capital, which can help to increase economic growth. Improvement in policies and institutions also creates a suitable environment for growth in domestic investment. As trust in institutions such as the rule of law and protection of private property grows, people feel more confident investing in the local economy.

Today, the size and the scope of global capital markets make Africa’s access to capital potentially easier than at any time in the past. Indeed, private capital flows to developing countries now dwarfs aid flows.

According to the Brookings Institution, ODA to African countries has fallen from “62 per cent of total external flows in 1990 to 22 per cent in 2012,” and the disappearing aid has been largely replaced by private capital. “The volume of external flows to the region increased from $20 billion in 1990 to above $120 billion in 2012. Most of this increase in external flows to sub-Saharan Africa can be attributed to the increase in private capital flows.”

Sub-Saharan Africa is the least economically free region in the world. There is a general consensus among economists that Africa needs to catch up with the rest of the world in terms of economic liberalization. Aid is often intended to promote policy reform, yet it has helped to create disincentives to liberalization for a number of reasons.

For example, aid is often driven by foreign policy considerations, not economics. For much of the Cold War, African countries were given bilateral and multilateral assistance on the basis of their geopolitical importance to the West and the Soviet Union. More recently, a 2015 study by AidData revealed that Chinese aid to Africa is used to both “promote Chinese foreign policy goals,” and advance “the economic interests of the Chinese state as well as Chinese firms operating abroad.” Likewise, American aid to African countries like Ethiopia is often strongly influenced by geopolitical interests. As a recent piece in the Harvard International Review noted, American aid to Ethiopia was long driven by a desire to prevent the spread of Islamic extremism in the country.

Aid has not led to economic reforms in Africa. In the 1980s, the World Bank started to promote structural adjustment loans that were meant to disburse aid to countries in exchange for their commitment to economic reforms. Such conditional lending soon proved ineffective, in part because aid agencies have no enforcement mechanism, and also because they have a well-known bureaucratic incentive to lend, which undermines the credibility of their conditionality.

In fact, aid may also actively retard policy reform. Between 1970 and 1993, for example, the World Bank and the IMF gave Zambia 18 adjustment loans with little or no reform staking place, forcing World Bank researchers to conclude that “this large amount of assistance sustained a poor policy regime.” More generally, two World Bank researchers concluded that “higher aid slowed reform [in the developing world] over the 1980–2000 period.”

Even in those countries that follow sensible macroeconomic policies, aid appears to have no positive effect and may go so far as to discourage reform. Some World Bank research claimed that developing countries that follow good fiscal, monetary, and trade policies benefit from foreign aid. But that research has been difficult to independently corroborate. Scholars who used updated World Bank data found no positive correlation between foreign aid and economic growth in countries with “good policies.” Research suggests that when governments do decide to undertake economic reforms, they tend to do so because of domestic factors, including economic crises.

In short, the theoretical case for foreign aid is, at best, questionable, and aid’s practical impact on some of the world’s poorest economies may well have been harmful.

This first appeared in CapX.