“If someone was ready to fork over $1 million to you to stop using the Internet – forever – would you do it?” Economics professor W. Michael Cox, who asked that question of his students, received an unambiguous reply. “You couldn’t pay me enough,” they answered. That answer speaks to just how priceless the internet has become, and how encouraging it is to see it spreading throughout the world, including to the poorest countries.

The internet’s ubiquity makes summarising its various uses a pretty daunting task. To start with, it is the repository of all human knowledge. Search engines provide answers to virtually all questions. Online videos explain billions of different topics and procedures. Users can take online courses and communicate with experts. New books are easily accessible in digital and audio forms, while old books are being digitised en masse. Publishing and broadcasting have been democratised. People can share their ideas easily and, if need be, anonymously.

Then there are the huge benefits to human communication. Letters that used to take weeks or months to arrive have been superseded by email and social media apps that make written contact instantaneous and practically cost-free. International phone calls were once very expensive. Today, video chats allow for a face-to-face conversation with anyone, anywhere. In the future, it may even be possible to download the contents of human brains onto a computer, thus enabling communication with people from beyond the grave.

The internet is also a great productivity enhancer. Online banking allows people conveniently to view their balances, pay their bills and make other transactions. Online shopping allows buyers to access most goods and services, compare their prices and read product reviews. Sellers can reach more people than could ever fit in a retail store. Research shows that much of US growth since the mid-1990s has been driven by internet-induced efficiency gains among large retailers, such as Walmart and, later, Amazon.

Our professional lives are more flexible too, with ever more of us able to work from home, avoiding an often costly and time-consuming commute. Online hiring gives employers easy access to a worldwide talent pool.

Of course, like all technologies, the internet can be used for nefarious purposes – just think of all those Nigerian email scams and “fake news” – but it is also an excellent resource for discovering the reputational standing of local doctors, lawyers, educators and restaurants.

As well as making people’s lives infinitely more convenient, the internet is a tool of humanitarian assistance and rising global consciousness. It makes it easier to raise, remit and donate money. That’s especially important during emergencies, such as wars and natural disasters, when speedy response from the donor community is necessary. And, it can alert the public to human rights abuses, such as the attempted ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya minority in Burma.

It has also been a boon for popular entertainment, allowing more people than ever to access movies, shows, concerts and live events from the comfort of their living rooms. It’s easy to forget there was once a time when the eccentric billionaire and insomniac Howard Hughes bought a local TV station just so he could watch his favourite movies. The station then broadcast films from a list that Hughes pre-approved. Today, almost everyone has access to thousands of titles on Netflix.

Put plainly, in today’s world, access to the internet is essential for full economic and political participation, as well as intellectual growth and social interaction.

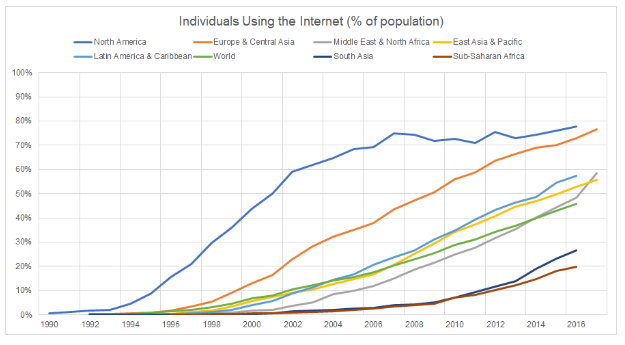

Thankfully, internet use is growing rapidly. Between 1990 and 2016, the share of the world’s population with access to the internet rose from zero to 46 per cent. It is expected to rise to 52 per cent by 2020. In 2016, the highest number of internet users was in North America (78 per cent) and the lowest was in sub-Saharan Africa (20 per cent). Those numbers are likely to increase, because the cost of internet “transit price” or sending data from one computer to another fell from $1,200 per megabyte per second (Mbps) in 1998 to $0.63 in 2015. In other words, the internet transit price is heading toward zero.

And plans are afoot to bring the internet to some of the poorest people in the world. Currently, traffic flows through expensive fiber optic cables. Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook and Elon Musk’s SpaceX are working on a system of internet satellites designed to provide low-cost internet service from Earth’s orbit. Google, in the meantime, wants to launch high-altitude internet balloons to the stratosphere, where they will catch a ride on wind currents to their destinations in the developing world.

The internet is now so ingrained in most of our lives that it’s easy to forget just how miraculous a technology it is. The fact this miracle is available to more and more of humanity is a cause for huge celebration.

This first appeared in CapX.