Are we running out of resources? That’s been a hotly debated question since the publication of Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb in 1968. The Stanford University biologist warned that population growth would result in the exhaustion of resources and a global catastrophe. According to Ehrlich, “The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now. At this late date nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate”.

The University of Maryland economist Julian Simon rejected Ehrlich’s thesis. In his 1981 book The Ultimate Resource, he argued that humans were intelligent beings, capable of innovating their way out of shortages through greater efficiency, increased supply, or development of substitutes. He wrote: “There is no physical or economic reason why human resourcefulness and enterprise cannot forever continue to respond to impending shortages and existing problems with new expedients that, after an adjustment period, leave us better off than before the problem arose.”

A just-released paper, which I co-authored with Brigham Young University economics professor Gale Pooley, revisits the Ehrlich-Simon debate. In The Simon Abundance Index: A New Way to Measure Availability of Resources, we look at prices of 50 foundational commodities covering energy, food, materials and metals. Our findings confirm Simon’s thesis. Between 1980 and 2017, the world’s population increased from 4.46 to 7.55 billion or 69 per cent. Yet resources have become substantially more abundant.

To arrive at our conclusion, we introduce four new ways of measuring abundance of resources. Ehrlich and Simon looked at inflation adjusted prices of commodities. By our count, those fell by 36 per cent. Taking that analysis a step further, we have come up with a “time-price” of commodities, which allows us to cost resources in terms of human labour. We find that relative to the average global hourly income, commodity prices fell by 64.7 per cent between 1980 and 2017.

Second, the price elasticity of population (PEP) allows us to measure sensitivity of resource availability to population growth. We find that the time-price of commodities declined by 0.934 per cent for every 1 per cent increase in the world’s population. Put differently, over the last 37 years, every additional human being born on our planet appears to have made resources proportionately more plentiful for the rest of us.

Third, we develop the Simon Abundance Framework, which uses the PEP values to distinguish between different degrees of resource abundance, from decreasing abundance at the one end to super abundance at the other end. Considering that the time-price of commodities decreased at a faster proportional rate than population increased, we find that humanity is experiencing super abundance.

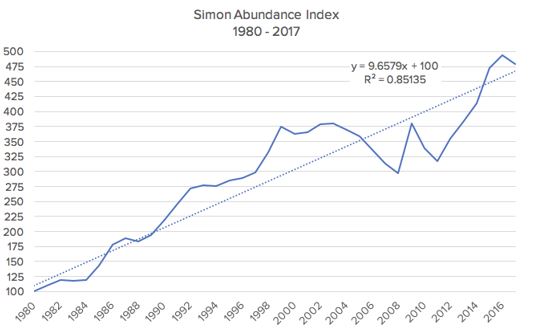

Finally, we create the Simon Abundance Index (SAI), which uses the time-price of commodities and change in global population to estimate overall resource abundance. The SAI represents the ratio of the change in population over the change in the time-price, times 100. It has a base year of 1980 and a base value of 100. Between 1980 and 2017, resource availability increased at a compounded annual growth rate of 4.32 percent. That means that the Earth was 379.6 percent more plentiful in 2017 than it was in 1980.

Based on our analysis of the relationship between resource availability and population growth, we forecast that the time-price of commodities could fall by a further 29 per cent over the next 37 years. Of course, much will depend on policies and institutions that nations pursue. For time-price of commodities to decline and resource abundance to increase, it is necessary for market incentives and price mechanism to endure. For it is when prices of commodities temporarily increase that people have an incentive to use resources more efficiently, increase their supply and develop cheaper substitutes.

Simon’s revolutionary insights with regard to the mutually beneficial interaction between population growth and availability of natural resources, which our research confirms, may be counterintuitive, but they are real.

The world’s resources are finite in the same way that the number of piano keys is finite. The instrument has only 88 notes, but those can be played in an infinite variety of ways. The same applies to our planet. The Earth’s atoms may be fixed, but the possible combinations of those atoms are infinite. What matters, then, is not the physical limits of our planet, but human freedom to experiment and reimagine the use of resources that we have.

This first appeared in CapX.