Summary: Kirstin Olsen’s book Daily Life in 18th-Century England captures a period of tremendous change, highlighting the stark differences in living conditions between 1700 and 1800. The 18th century saw advancements like the development of effective steam engines and profound new scientific knowledge, which led to improved comfort even for the poor by 1800. Olsen elucidates the immense hardships commonplace in English society prior to industrialization, from the evolution of marriage and childbirth to the grim realities of public entertainment, criminal justice, and healthcare.

Kirstin Olsen’s book Daily Life in 18th-Century England paints a vivid portrait of a time of immense change. “There were no really effective steam engines in 1700, no awareness that ‘air’ and ‘water’ were divisible into separate elements, no understanding of why things burned, and no knowledge of positive and negative electrical charges. The words ‘mammal’ and ‘Homo sapiens’ did not exist. No one had ever flown, and no one, since prehistory, had discovered a new planet in the sky. Weaving and spinning were still done entirely by hand. By 1800, all this would change.” Living conditions transformed so that even “the poor were much more comfortable in 1800 than in 1700.” This book provides a thorough look into everyday life just prior to the dawn of industrialization as well as during that momentous transition, which began around 1760 in Britain.

In the 18th century, people seldom traveled and lived in hyperlocal worlds. “Weights and measures still varied from one region to another. . . . Cornish was still spoken in parts of the far southwest until about 1780, and Welsh and Gaelic were still in common use in areas outside England. Most residents of the Isle of Man spoke their own language, Manx, as well.”

Given the highly limited pool of marriage partner choices that resulted from this extreme isolation, perhaps it is unsurprising that “much of the satirical literature of the 18th century . . . lampooned marriage as a hell or prison sentence for one or both partners. The most typical attitude toward marriage evinced in 18th-century literature and visual art is a sly, collegial misery.” The poem “Wedlock” by the English poet Mehetabel “Hetty” Wright (1697–1750), herself pressured into a loveless marriage with a plumber (who trekked home grime that may have been responsible for their losing many children to premature death), paints a typical picture:

Thou source of discord, pain and care,

Thou sure forerunner of despair,

Thou scorpion with a double face,

Thou lawful plague of human race,

Thou bane of freedom, ease and mirth, [. . .]

Who hopes for happiness from thee,

May search successfully as well

For truth in whores and ease in hell.

Legally “the groom could be as young as 14 and the bride as young as 12.” Many marriages turned abusive. “Domestic violence was tolerated by the courts so long as it was limited to ‘moderate physical correction,’ and a man could even commit his wife to an insane asylum against her will.” An abused woman’s best hope was often not legal recourse but the possibility that a male relative, neighbor, or sympathetic passerby might notice her plight and take action on her behalf. “Neighbors [sometimes] intervened when men beat their wives, shaming the abusers with public processions and chants, or simply stopping beating, as a saddler did in 1703, telling the abusive husband, ‘You shall not beat your wife.’” Remaining single in the 18th century brought its own challenges: “The life of a spinster could be a difficult one, with extended family using unattached female relatives as temporary live-in housekeepers when a wife died.”

Those who imagine that the people of the past unfailingly adhered to stricter standards of chastity might be alarmed at the frequency of shotgun marriages: “One-third of all brides were pregnant at their weddings.” About 20 percent of first births occurred outside marriage in 1790 in England. Such children were often subject to neglect and even infanticide. In England: “A 1624 statute criminalized concealing the death of a bastard child unless the mother (who in this was presumed guilty) could prove that it had been stillborn.”

“It was common for one parent to die before all the children had grown up.” The 18th-century “Birmingham businessman William Hutton received a straightforward appraisal of his chances when, as a child, he lost both his parents. ‘Don’t cry,’ his nanny told him. ‘You will soon go yourself.’” (He defied this prophecy: After a long life that included beginning work in a mill at age 7, he died at the ripe old age of 91).

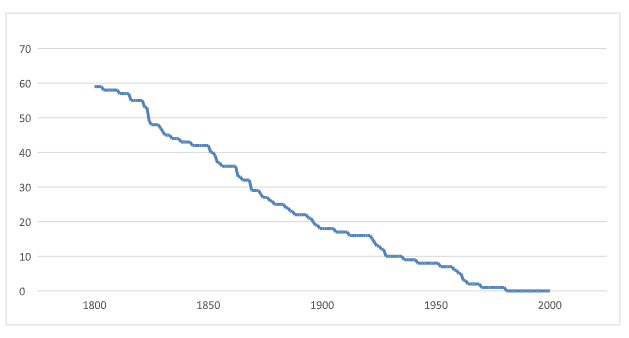

“Childhood ailments claimed a large number of children before their fifth birthdays (60 percent in London in 1764), and those illnesses that failed to kill often scarred or attracted treatments that were even worse. A child might have to survive teething problems, tapeworms, chicken pox, whooping smallpox, lead poisoning, thrush, measles, and mumps, being bled, swaddled, and dosed with belladonna, syrup of poppies (opium), quinine, rum, gin, brandy. Laxatives, and patent medicines. Children wore amulets of such ingredients as mistletoe and elk’s horn, had hare’s brains smeared on their gums while teething, and were given enemas for worms. A particularly drastic worm remedy involved inserting a piece of pork on a string into the rectum and drawing it out slowly to lure the worms. Some diseases could be cured, it was thought, by a sudden fright, such as riding on a bear, having a gun fired nearby, or ‘giving the patient a part of some disgraceful animal, as a mouse, etc., to eat, and afterwards informing him of it; and so forth.’”

“Imagine that you are sick in the 18th century. You are running a high fever, feeling light-headed, and beginning to develop blotches on your skin. Your mother has dosed you with some cheap patent medicines. She has tried poultices and some sort of nasty-smelling broth. Time passes, and a man with a cane and a sword feeds you more bad-tasting medicines. You think you hear him say that one is made of spiders. You are dimly aware of warm water and a pain in your arm, and you turn your head to witness the sight of your blood running from a vein in your elbow into a bowl. Ah, good, you think, being an 18th-century person. Everything that can be done is being done.”

In those days, sometimes avoiding doctors altogether was better than receiving what passed for medical treatment. “Needing to do something dramatic, or for lack of anything better to do, or because they really believed it would work, doctors resorted to visible but useless or even harmful measures-bleeding, dosing with dangerous drugs, raising blisters on the skin, and inducing vomiting. [Joseph] Addison, in The Spectator, called physicians ‘a most formidable Body of Men: The Sight of them is enough to make a Man serious, for we may lay it down as a Maxim, that When a Nation abounds in Physicians it grows thin of People.’”

Folk remedies were also usually useless and often dangerous. “They ate soap for stomach troubles, touched hanged men to cure goiter and swollen glands, drank asses’ milk, made charms of babies’ amniotic sacs, drank their own urine for ague or snail tea for a sore chest, rubbed their eyes with black cats’ tails for styes, and ate eye of pike for toothaches, pigeon blood for apoplexy, tortoise blood for epilepsy, cockroach tea for kidney ailments, puppy and owl broth for bronchitis, and spiders for fever.”

Beauty products could be harmful too. “Most cosmetics were made at home” even in the 1700s, with some recipes “containing harmful chemicals like the white lead in face paint or the mercury in some rouges” and others included irritants such as quicklime or even “cat’s dung.” “Some reportedly also wore false eyebrows made of mouse skin that could, in a hot room, begin to slide down an unfortunate woman’s face.”

The state of dentistry was similarly dreadful. “If something went wrong with the teeth, dentists hand-drilled cavities as always, with no anesthetic but alcohol and filled the resulting holes with molten tin, lead, or gold. Where a dentist was unavailable, one called the farrier (the horse-doctor). False teeth were made of bone, ivory, gold, porcelain, wood, or the purchased teeth of the poor, but such dentures were expensive and, held in place by awkward spring mechanisms, sometimes fell out of the mouth. Tooth problems could also result in infections; 780 Londoners ostensibly died in 1774 from dental problems.”

Standards of sanitation were also unacceptable. London’s streets were “full of sewage and horse dung and butchers’ offal.” “The streets were atrocious in the first half of the [18th] century, full of dust in dry weather and mud in wet. These streams were augmented by dirtied water tossed by maids from the upper stories, by gutters that ran directly onto the streets and pavements, and by rainstorms, which carried into them ‘Sweepings from butchers’ stalls, dung, guts, and blood, / Drowned puppies, stinking sprats, all drenched in mud, / Dead cats and turnip tops.’ The streets were dirtied by not only horse manure but also human waste, particularly from beggars and children who urinated and [defecated] next to buildings.” In the 1760s, just as industrialization began, so too did the condition of London’s streets start to improve.

Mental health care was appalling as well. A chief amusement of the pre-industrial world was finding entertainment in the act of gawking at anyone unusual, especially those suffering from bodily abnormalities or mental health problems. “The interior of a madhouse such as London’s Bethlehem Hospital (Bedlam) was a sight to behold, and many did—Bedlam was one of London’s principal tourist attractions, and until 1770, visitors could pay for admission and a tour, during which guards and visitors alike goaded the inmates to view their violent reactions. Nuts, fruit, cheesecakes, and beer were sold to the tune of ‘rattling of Chains, drumming of Doors, Ranting, Hollowing, Singing,’ and the distinctive uproar that spread like a wave through the asylum when the inmates became outraged at the treatment one of their fellows was receiving. Some inmates fought back by hurling the contents of their chamber pots. Bedlam’s occupants were lightly dressed in both summer and winter, in unheated rooms. Often with only a pile of straw for a bed.” It was somewhat unusual when in London, the rather distastefully named St. Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics, “founded in 1751, explicitly forbade exposing ‘the patients . . . to public view.’”

Executions and other criminal punishments were another popular form of entertainment. There were about 200 capital crimes (for which the punishment was death) in England as late as 1800, including pickpocketing goods over 1 shilling in value, shoplifting 5 shillings’ worth, sheep-stealing, killing a cow, entering land with intent to kill rabbits, “associating with gypsies,” theft of a master’s goods by a servant, and vandalism of fishponds.

Lesser crimes were punished with public shame. “People exposed in the pillory were tormented by the crowd, sometimes for fun and sometimes out of genuine resentment of the crime. It was not unusual-for-the-person pilloried to suffer death or maiming as a result of being pelted with stones, food, dirt, dead animals, and trash. Those not pilloried were sometimes branded, though the brander could be bribed to use a cold iron. Another common punishment was public flogging, and it was a holiday of sorts when women, particularly prostitutes, were flogged. Crowds would gather to see these women stripped to the waist and beaten. The holiday mood only intensified when a hanging was scheduled.” Hence in the 1730s, one writer observed of England, “The Execution of Criminals here is a perfect Shew to the People, by Reason of the Courage with which most of ’em go to the fatal Tree. . . . I lately saw five carried to the Gallows, who were dressed, and seemed to be as well pleased, as if they were going to a Feast.”

A festival-like atmosphere attended public hangings, which were a major source of entertainment. “At Tyburn the crowd either stood or paid for the privilege of sitting in the wooden grandstands, called ‘Mother Proctor’s Pews.’ The cart moved beneath the gallows, and there were final speeches from the condemned, perhaps a last-minute reprieve, prayers from the chaplain, the nooses placed around necks. Then ‘away goes the Cart, and there swing my Gentlemen kicking in the Air.’ Hawkers began selling the alleged dying utterances of the hanged, which made the execution, 1 sale being far more important than factual accuracy. Sufferers from disease snatched at the bodies, believing them to possess magical powers. Entrepreneurs waited for the right moment to make off with the rope, which could be sold in pieces as a souvenir. Friends red lingered, trying either to support them long enough to cut them down (which worked on at least one occasion) or to yank their legs to shorten their suffering (since 18th-century hanging had no drop to break the neck, and death was by slow strangulation) and defending their bodies (sometimes with fierce violence) from the surgeons, who had a right to dissect 10 Tyburn corpses per year and claimed any corpse not purchased by the family. In some cases, the bodies were violated according to the nature of the crime. Jacobites’ heads were, until 1777, severed and displayed on spikes at Temple Bar. Sometimes whole bodies, often shaved, disemboweled, or coated with tar or tallow, were hung in chains near the symbolic scene of their crimes—along roads for highwaymen and near the Thames for pirates, mutineers, and deserters. Far from being shocked by such displays, the crowds positively demanded them. They sometimes rioted if denied a hanging, for example by the suicide of the condemned. In one such case, they seized the dead body and attacked it with such ferocity that virtually all its bones were shattered.”

People also commonly enjoyed violence against animals as entertainment. “The torture and killing of animals and fights between humans were a prime source of entertainment. Thus, in 1730, a showman advertised ‘a mad bull to be dressed up with fireworks and turned loose in the game place, a dog to be dressed up with fireworks over him, a bear to be let loose at the same time, and a cat to be tied to the bull’s tail.’ Some impresarios staged dog fights, or tied an owl to the back of a duck to see the duck dive in fear and half-drown the owl, or hung a goose head-down from a tree or a pair of poles, greased its neck, and gave people turns trying to pull off its head while riding underneath. Children’s games included shooting flies with small guns, sewing a string to a mayfly to keep it on a leash, and ‘conquering,’ or pressing snails against each other till one shell broke.”

“One of the most popular blood sports was cockfighting. Participants of all classes came to the cockpit with sacks holding their prize roosters, whose wings and tails had been clipped and whose legs were fitted with long sharp spurs called gaffles. Amidst a roar of betting, two cocks were placed in the ring and pushed at each other until they began to fight. ‘Then it is amazing,’ wrote one spectator, ‘to see how they peck at each other, and especially how they hack with their spurs. Their combs bleed terribly and they often slit each other’s crop and abdomen with the spurs.’ Battle continued until one of the birds stood crowing on its dead opponent’s body.” One witness to such a battle in 1728 wrote, “Cocks will sometimes fight a whole-hour before one or the other is victorious.”

“Another popular spectacle was the ‘baiting’ of an animal by tying it up and sending dogs against it. The most popular animal for such contests was a bull. In fact, in some places, it was illegal for a butcher to slaughter a bull without first making it the subject of such sport.”