We owe many popular Christmas traditions to Victorian England, from carols and decorated trees to gift-giving. These cheerful traditions stand in stark contrast with our recognition of the nightmarish working conditions at the time. In Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, for example, the miserly businessman Ebenezer Scrooge exemplifies the alleged spirit of the Victorian age: heartlessness, he maintains, is good for business.

Underneath the veneer of destitution and exploitation of the era, however, things were changing for the better. The unlikely and seldom acknowledged benefactor of the poor in 19th century Britain was the factory.

When asked to picture a scene of horrifying working conditions during the Victorian era, most people conjure up the image of a 19th century factory. Yet the life of a housemaid was, at that time, far bleaker than that of most “factory girls.” That is one of many surprising insights that can be found in Judith Flanders’ fascinating book, Inside the Victorian Home: factories helped improve working conditions, especially for women.

In 1851, one in three women between the ages of 15 and 24 in London worked as a domestic servant. Their work was often excruciating, and it is no wonder that many of them rushed at the opportunity to join factories and leave domestic service.

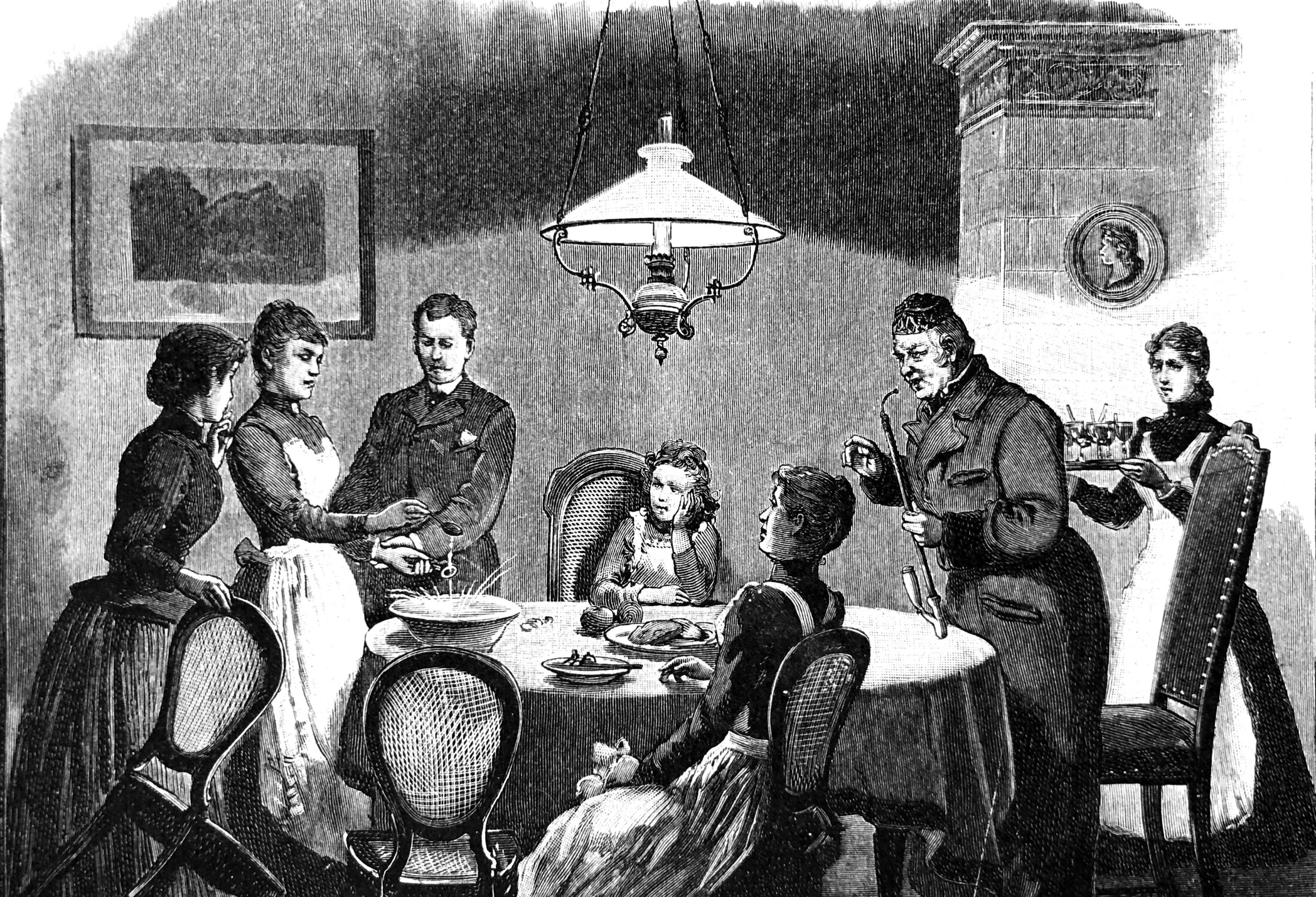

First, consider how health conditions differed for factory and domestic workers. An average housemaid “had less fresh air than a factory worker,” according to Flanders. The kitchens and sculleries of well-to-do Victorian homes, where the servants spent much of their time, were particularly unhygienic. Rats were tolerated, as servants focused their efforts on the more numerous threat: bugs. The typical “kitchen floor at night palpitate[d] with a living carpet” of cockroaches, and the typical kitchen ceiling was crawling with beetles. When the author Beatrix Potter visited her grandparents’ home in the summer of 1886, her servants “had to sit on the kitchen table [while working], as the floor heaved with cockroaches.”

As if the health hazards weren’t bad enough, consider the exhausting working hours. A typical housemaid “did at least twelve hours of heavy physical labor every day, which was two hours more than a factory worker (four hours more on Saturdays).” Also, unlike most factory workers, house servants rarely had Sundays off. A typical servant’s workday began at six o’clock in the morning at the latest, no later than five-thirty in the summer, and didn’t end until ten at night — at the earliest. Working from five in the morning until midnight was not unheard of. Servants faced an almost impossible-to-complete list of daily tasks that left practically no time to eat, rest, or clean their own quarters, let alone engage in leisure activities.

A “maid-of-all-work” or “general servant” might begin the day by drawing the home’s curtains and opening the shutters, cleaning the household’s grate, fire irons and fender, and then lighting the hearth fire. She might then dust the furniture and strew used tea leaves over the carpets to collect dust, then sweep them up again. She might sweep the hall, front steps and entrance, shaking out the rugs, and scrubbing and washing the floor — which was a laborious process before the invention of modern cleaning products. She would empty the fireplaces of cinders, ending up covered in soot. And that was just the early morning work! A moment’s idleness was not tolerated. While cruel factory foremen may loom large in the public imagination, physical punishment of servants was common.

But contra Scrooge, cruelty was often bad business — and certainly bad for employee retention. As factory work became more widespread, it improved working conditions for house servants too, as employers competed for women’s labor. Employers were “forced to slowly improve servants’ working conditions” or risk losing all their servants to the factories. In 1872, one Victorian complained “that it was now necessary… to allow their maids to go to bed at ten o’clock every night, and to give them an afternoon out every other Sunday, or no servant would stay.”

Today as well, in industrializing countries, the same story of improving working conditions is repeating. Social economist Naila Kabeer of the London School of Economics has found that for women in Bangladesh, “factory work [has] offered higher returns, better working conditions and greater dignity than they had obtained from personalized, isolated and menial forms of labor previously available to them” such as domestic service.

A Christmas Carol ends with a newly reformed Scrooge raising an employee’s salary as an act of kindness. Historically, the higher salaries and improved conditions of Victorian workers were largely driven by industrialization. Those who imagine that poor working conditions originated with the Industrial Revolution should consider the difficulties faced by many house servants. While 19th century factory work was harsh compared to the post-industrial prosperity enjoyed by many today, factories ultimately helped to improve working conditions for Victorian women — and continue to do so for many women today.

This first appeared in the American Spectator.