A shocking statistic has come to light: Venezuelans lost 19 pounds on average over the past year because of food shortages.

There was a time when hunger was a near-universal experience. As Kevin D. Williamson put it, “Not long ago, the great dream and aspiration of most of the people walking this Earth was to have enough to eat, for themselves and for their children, and to be liberated from worrying about whether they would eat again tomorrow or the next day.”

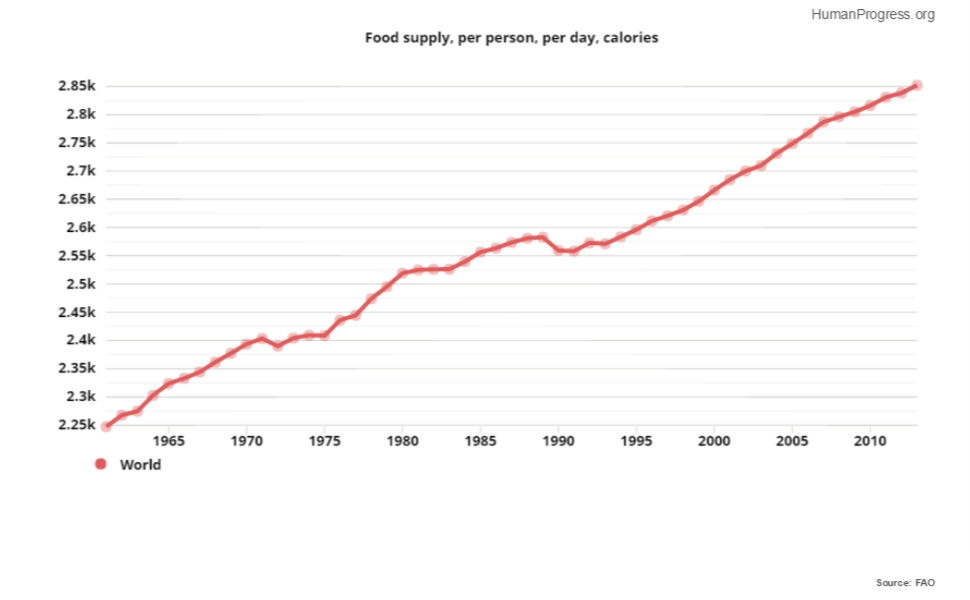

Then, something changed. Exchange and specialization helped bring down food prices. A burst of innovations called the Green Revolution led to higher agricultural productivity and decreased food priceseven further. Even as the world’s population grew, the market ensured that the supply of food rose to meet growing demand.

The global numbers are heartening. The share of the world’s population suffering from hunger is shrinking. Despite population growth, the total number of undernourished persons is lower as well. Even those who are food-deprived are less severely malnourished than in the past. Humanity now produces more than enough food to theoretically feed everyone on Earth the recommended 2,000 calories per day.

Hunger was declining in Venezuela too until recently. The percentage of Venezuela’s population suffering from undernourishment fell from 14% in 1991 to “5% or lower” in 2015, the latest year for which the United Nations has data. Since then, the situation has rapidly deteriorated. In a single year, the number of cases of severely undernourished children in Venezuela’s capital city, Caracas, doubled.

The reason? Venezuela’s socialist economic policies, briefly sustained by fleeting high oil prices, led to hyperinflation and a societal collapse. If Venezuela continues on its present course, hunger is likely to become more widespread.

We can all be thankful that undernourishment has become rarer globally. But the case of Venezuela demonstrates that progress is not inevitable—suicidal economic policies, like socialism, can rapidly extinguish the prosperity we enjoy.

The first appeared in Cato at Liberty.