The free market, some people allege, is incompatible with workplace safety. Competition drives down profits, the German philosopher Karl Marx asserted, which forces business owners to cut corners and expose their workers to growing risks. Yet, by historical standards, work-related fatalities are at an all-time low. Labor activism and government regulations deserve part of the credit for that happy state of affairs. But, a general improvement in living standards and, consequently, higher expectations on the part of the laborers, also played a part in improving workplace safety. Plainly put, a safer workforce is a more contented workforce. It is in the interest of the employers not to expose their workers to unnecessary risks.

All economic activity involves some degree of physical risk. That has always been the case. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors had to contend with wild animals, poisonous snakes and other vagaries of nature that surely make the modern workplace a much safer alternative. Credible data on work injuries and fatalities during the agrarian era is difficult to come by, because most farm laborers were self-employed. Simply put, no entity, official or otherwise, had an incentive to collect occupational safety statistics. Yet agricultural work must have been quite unappealing, considering that most people preferred factory work over life on the farm.

Even today, notes the U.S. Department of Labor, agriculture “ranks among the most dangerous industries.” In 2011, the “fatality rate for agricultural workers was 7 times higher than the fatality rate for all workers in private industry; agricultural workers had a fatality rate of 24.9 deaths per 100,000, while the fatality rate for all workers was 3.5.” Likewise, the Workplace Safety and Health (WSH) Institute in Singapore found that global fatality rates per 100,000 employees in agriculture ranged from 7.8 deaths in high-income countries to 27.5 deaths in South-East Asia and Western Pacific regions in 2014. Manufacturing deaths ranged from 3.8 in high-income countries to 21.1 in Africa.

Collection of statistics came about as a result of industrialization and the birth of modern labor relations in the 19th century. Labor unions started to collect workplace safety statistics in order to achieve more advantageous working conditions for their members, while employers kept work safety data, because they were legally liable for injuries in the workplace. By modern standards, it is clear that working conditions in mines and factories during the first 100 years of the Industrial Revolution were appalling. As the then-U.S. President Benjamin Harrison put it in 1892, “American workmen are subjected to peril of life and limb as great as a soldier in time of war.”

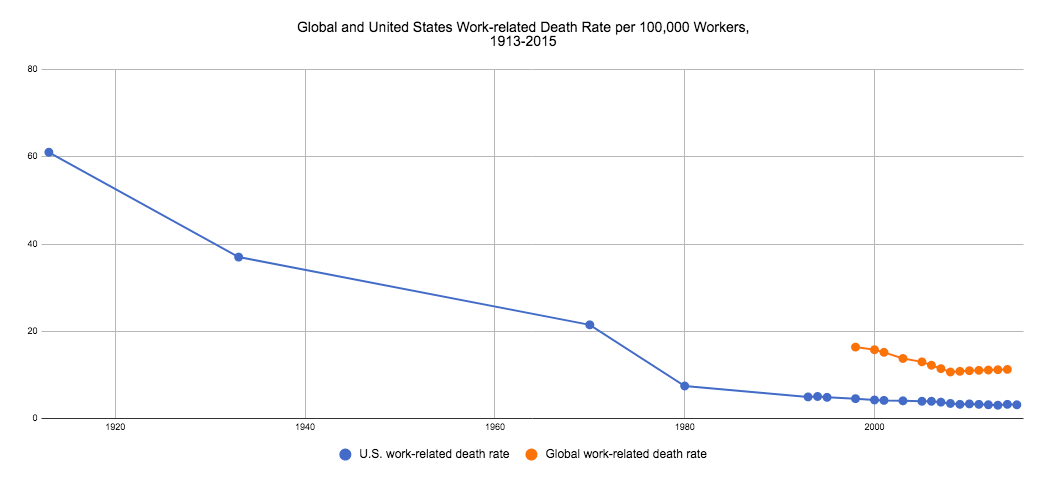

In the United States, estimates Harvard University psychologist Steven Pinker in his 2018 book Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress, 61 workers per 100,000 employees died in work-related accidents as late as 1913. That number fell to 3.2 in 2015. That’s a 95 percent reduction in work fatalities over a little more than 100 years. A similarly encouraging trend can be observed globally. According to the WSH Institute estimates, 16.4 workers per 100,000 employees died worldwide in 1998. By 2014 that number fell to 11.3. That’s a 31 percent reduction over a remarkably short period of 16 years. Considered in a slightly different way, workplace fatalities around the world seem to be falling by almost 2 percentage points each year.

What accounts for those improvements? Labor union activism, including strikes and protests, has been traditionally credited with making the workplace safer. But, improving working conditions cannot be divorced from the overall improvement in the standard of living. The massive economic expansion in the second half of the 19th century, in particular, tightened the labor market and workers started to gravitate toward more generous employers. It was only after a certain critical mass of workers achieved more tolerable working conditions that more general workplace regulations became imaginable and, more importantly, affordable.

Thus, at least in the American context, the reduction in workplace fatalities preceded the Wagner Act of 1935, which enabled private sector employees to organize into trade unions, engage in collective bargaining and take collective action. By the time that the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration was created in 1971, worker fatalities were roughly two-thirds lower than what they have been prior to World War I. Thus, as with working hours, government regulations tend to affirm that which is already happening in the labor market place anyway.