Today marks the 50th, and final, installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org titled Heroes of Progress. Over the last two years, this bi-weekly column has provided a short introduction to heroes who have made an extraordinary contribution to the well-being of humanity. You can find the 49th part of this series here.

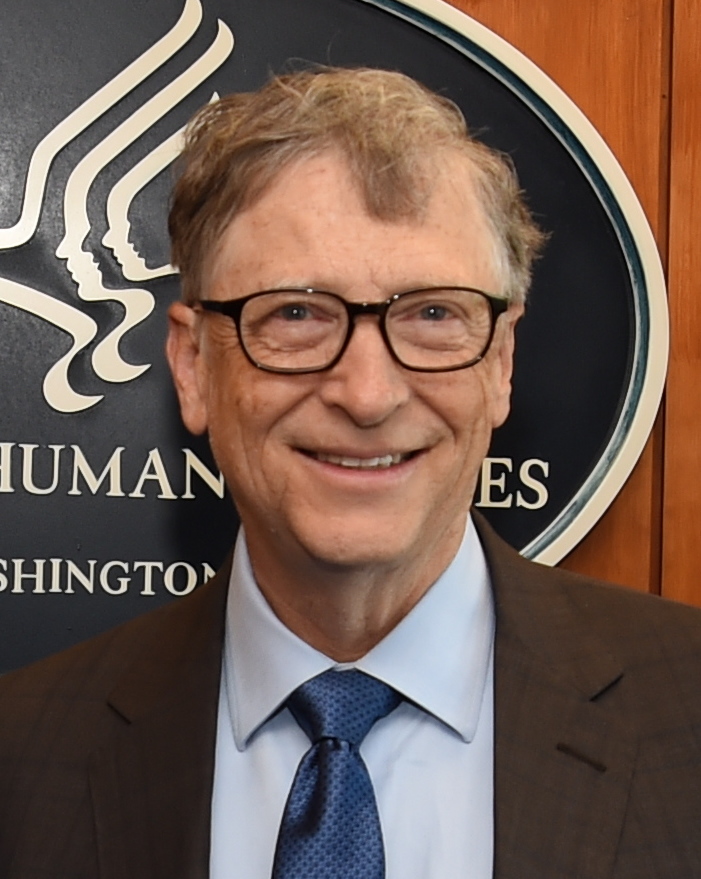

This week, our hero is Bill Gates – an American software developer, businessman, and philanthropist. Thanks to Microsoft, the company that Gates co-founded, personal computers went from being used almost exclusively by computer hobbyists, to being a staple in millions of homes and offices around the world. By helping to make computers available to the masses, Gates’ work dramatically changed the world we live in and made many once-complicated tasks much simpler. Moreover, global productivity increases enabled by his computers have likely added trillions to the world’s economy.

Gates has also created several charitable organizations, and alongside his wife, he created the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation – the world’s largest philanthropic organization. Through providing education, vaccinations, investment in infrastructure, combatting diseases, and building improved sanitation facilities, Gates’ philanthropic endeavors have improved the lives of hundreds of millions of the world’s poorest people and helped to save tens of millions of lives.

William Henry Gates was born on October 28, 1955, in Seattle, Washington. His father was a well-known lawyer, and his mother served on the board of serval large companies. Gates grew up in a household he’d later describe as “well-off” and his two sisters have described him as a happy child. At a young age, Gates showed signs of competitiveness and intelligence. He excelled at playing the board games Risk and Monopoly, and he would often spend hours a day reading.

At 13 years old, Gates began studying at Lakeside School, an exclusive private school in Seattle. Gates performed exceptionally in nearly all his subjects but had a unique aptitude in math and science. He later noted that through the 8th grade, he enjoyed the fact he was able to do reasonably well in school without any effort.

Soon after Gates arrived at Lakeside, the school obtained a teletype terminal (an electromechanical teleprinter), and a local computer company offered Lakeside students some time on their computers. Gates quickly became fascinated with computer software. He spent much of his free time working at the teletype terminal and was even excused from other lessons to pursue this interest. During this time, Gates wrote his first-ever computer program – a game of tic-tac-toe.

Gates forged several friendships in the school’s computer room, notably with Paul Allen, Microsoft’s other co-founder, Ric Weiland, Microsoft’s first employee, and Kent Evans, Gates’ best friend and first business partner. One summer, Gates and his friends were banned from the local computer shop after they were caught exploiting bugs in the system to gain free computer time. After the ban, the four students formed the “Lakeside Programmers Club” to make money. The club volunteered to help the computer store fix the bugs in their software.

In 1971, Gates and Evans began to automate Lakeside’s class-scheduling system to make timetables for the students. Unfortunately, at the end of the school year, Evans died in a mountain climbing accident. Gates was deeply saddened by Evans’ passing and turned to Allen to help finish the project.

Although Allen was two years older than Gates, and despite the pair not always seeing eye-to-eye, the two teenagers quickly became friends and bonded over their passion for software. When Gates was 17, he and Allen formed their first business venture called “Traf-o-Data” – a computer program that helped monitor traffic patterns in Seattle. The pair made $20,000 for their work.

In 1973, Gates graduated from Lakeside with an extraordinarily high SAT score of 1590 out of 1600. In the Fall, he enrolled at Harvard University. Although Gates’ major was in pre-law, he spent most of his time at Harvard studying mathematics and graduate-level computer science.

In 1975, Gates read about the new Altair 8800 microcomputer kit in the magazine Popular Electronics. Gates and Allen decided to write to the company that created the Altair, Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems (MITS), to gauge their interest in having someone build a software program that could run on the computer. To do that, Gates decided to call the President of MITS from his dorm phone.

Gates told the President that he had already created the software and attempted to sell MITS the program. In reality, neither Gates nor Allen had an Altair machine, and the pair hadn’t written a single line of code for the computer. The President at MITS asked for a demonstration, and Gates and Allen spent the next month working relentlessly in Harvard’s computer lab writing the code. “From that moment,” Gates later remembered, “I worked day and night on this little extra credit project that marked the end of my college education and the beginning of a remarkable journey with Microsoft.”

In spring 1975, Allen and Gates traveled to MITS’ offices in New Mexico to test run the code. Despite never having tested the code before, the demonstration was a success, and both Allen and Gates were hired by MITS. Gates never returned to study at Harvard.

While working at MITS, Gates and Allen also formed their own partnership, which they named “Micro-Soft” – a combination of the words “microcomputer” and “software.” The company focused on developing programming language software for a variety of different systems. By 1976, Gates and Allen left MITS, dropped the hyphen in their company’s name, registered the name “Microsoft,” and opened their first office in Albuquerque, New Mexico. In the same year, Gates and Allen also hired their old high school friend Ric Weiland as Microsoft’s first employee.

By 1979, Microsoft was grossing approximately $2.5 million a year. In 1980, Microsoft struck a deal with IBM to provide the basic operating system that would run on IBM’s new computers. Although the contract with IBM only earned Microsoft a small fee, the prestige of doing business with one of the world’s largest corporations helped transform Microsoft into one of the world’s leading software companies.

In 1981, Microsoft, formerly a partnership between Allen and Gates, was reorganized as a privately held corporation. Aged 23, Gates was made CEO and chairman of the board, and the offices moved to Bellevue, Washington. For the first five years of Microsoft’s existence, Gates personally reviewed and often rewrote every line of code the company created. By 1983, about 30 percent of the world’s computers ran on Microsoft software, and the company established subsidiaries in England, Japan, and France. In the same year, Allen left Microsoft.

In November 1985, Microsoft released the first retail version of Microsoft Windows. The program sold well, and in 1986, when Microsoft went public, Gates became the world’s youngest billionaire. Since then, Gates has continually been one of the world’s richest people.

In 1989, Gates released Microsoft Office, which included the early versions of applications such as Microsoft Word and Excel. In 1995, Microsoft released the operating system Windows 95. The software marked an enormous leap forward in terms of both graphics and, most importantly, the design of operating systems, and sold rapidly.

Thanks to the Windows operating system, computers were no longer too complicated for the everyday person to use. Internet Explorer was released a few weeks after Windows 95. For the first time, millions of people began to use the internet. After 1995, a personal computer revolution began. In the years that followed, the price of computers dropped, and computer ownership skyrocketed. To this day, Microsoft remains one of the largest corporations in the world.

In 2000, Gates stepped down as CEO of Microsoft. Since then, he has focused most of his efforts on the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation – a philanthropic organization that he set up with his wife in 1994.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is involved in many different fields, including tackling poverty in Washington State, increasing access in the developing world to basic sanitation facilities, educating women, reducing HIV infections and extending the lives of those with that virus, tackling malaria, and working to completely eradicate polio. Since 1994, Bill and Melinda Gates have donated more than $50 billion to a variety of causes.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation also created Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance, in 2000. Since then, Gavi has helped vaccinate more than 760 million children and has prevented more than 13 million deaths. All in all, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has improved the lives of hundreds of millions of the world’s poorest people.

During a TED talk in 2015, Gates famously warned that the world was not prepared for the next pandemic. Over the last few years, Gates has spent millions on novel virus preparedness, and since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Gates has invested hundreds of millions of dollars in efforts to curb the outbreak. He has recently said that if necessary, he is prepared to invest billions of dollars into building factories for a vaccine.

Gates and his close friend Warren Buffet also created a campaign called The Giving Pledge, which encourages the extremely wealthy to donate the majority of their wealth to charitable causes. So far, 204 people have signed the campaign, pledging a total of $1.2 trillion to charity.

Today, Gates lives with his wife in Washington State. Throughout his life, Gates has received dozens of awards and honors. Time magazine named Gates as one of the most influential people of the 20th century. In 2005, he was given an honorary knighthood by the United Kingdom’s Queen Elizabeth II. In 2016, he and his wife Melinda were awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Gates also holds many honorary doctorates from universities across the world – including from Harvard, from which he dropped out.

Thanks to Bill Gates, computers went from being used almost exclusively by hobbyists who spent hours learning the complex languages necessary to operate a PC, to a vital, easy-to-use product that is utilized by billions of people. And through his philanthropy, Gates has saved tens of millions of lives and helped to improve hundreds of millions more. For these reasons, Bill Gates is rightfully our 50th, and final, Hero of Progress.