Today marks the 44th installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org titled Heroes of Progress. This bi-weekly column provides a short introduction to heroes who have made an extraordinary contribution to the well-being of humanity. You can find the 43rd part of this series here.

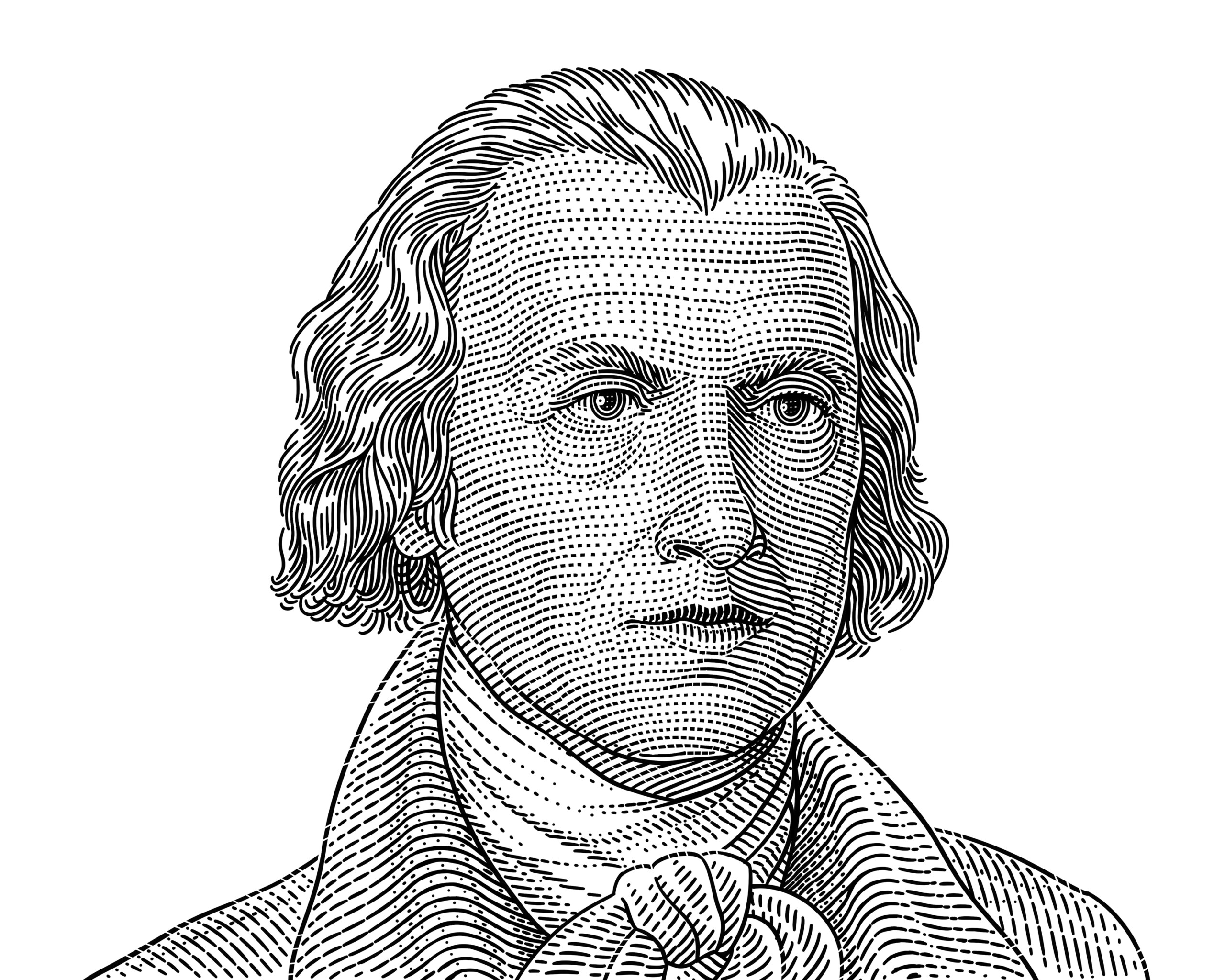

This week, our hero is James Madison. Madison was a Founding Father and the fourth president of the United States. He composed the first drafts, and thus the basic frameworks, for the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights. Madison is often dubbed the “Father of the Constitution” and he spent much of his life ensuring that the U.S. Constitution was ratified, and that freedoms of religion, speech and the press were protected under the law.

James Madison was born on March 16, 1751 in Port Conway, Virginia. Madison was raised on his family’s plantation. His father was one of the largest landowners in the Piedmont area. Although Madison was the oldest of twelve children, just six of his siblings would live to adulthood (a common occurrence at that time – even among the wealthy). In the early 1760s, the Madison family moved to the Montpelier estate in Virginia.

As a teenager, Madison studied under several well-known tutors. Unlike most wealthy Virginians of his day, he did not attend the College of William and Mary. Instead, in 1769, he enrolled at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), which Madison chose primarily for the College’s hostility to episcopacy. Despite being an Anglican, Madison was opposed to an American episcopate. He saw it as a way of strengthening the power of the British monarchy, and as a threat to the colonists’ civil and religious freedoms.

At the College of New Jersey, Madison completed his four-year course in just two years. After graduating in 1771, Madison remained in New Jersey to study Hebrew and political philosophy under the college’s president (and another future Founding Father) John Witherspoon. Madison’s thinking on philosophy and morality were strongly influenced by Witherspoon. Terence Ball, a biographer of Madison, noted that in New Jersey, Madison “was immersed in the liberalism of the Enlightenment and converted to eighteenth-century political radicalism.”

In 1773, Madison returned to Montpelier. Without a career, he began to study law books and soon took an interest in the relationship between the American colonies and Great Britain. In 1775, when Virginia began preparing for the Revolutionary War, Madison was appointed as a colonel in the Orange County militia. As he was frequently in poor health, Madison never saw battle and soon gave up on a military career. Instead, he pursued a political one. In 1776, Madison represented Orange County at the Virginia Constitutional Convention, where he helped to design a new state government, independent from British rule.

During his time at the Virginia Constitutional Convention, Madison often fought for religious freedom and he was successful in convincing delegates to alter the Virginia Declaration of Rights to provide for “equal entitlement” rather than just “tolerance” in the exercise of religion. While at the Convention, he met his lifelong friend, Thomas Jefferson – a Founding Father, who became the 3rd President of the United States.

Following the enactment of the Virginia Constitution in 1776, Madison became part of the Virginia House of Delegates and was soon elected to the Council of State for Virginia’s Governor, who was then Thomas Jefferson. In 1780, Madison travelled to Philadelphia as a Virginia delegate to the Continental Congress – a body of delegates from the thirteen American colonies that would create the United States of America.

The Articles of Confederation were ratified by the Constitutional Congress in 1781 and served as the first Constitution for the thirteen colonies. The Articles gave great powers to the states, which acted more like individual countries, than as a union. Madison felt that this structure left the Congress weak and gave it no ability to manage federal debt or to maintain a national army. Determined to change that, Madison began studying many different forms of governments.

In 1784, Madison re-entered Virginia’s legislature and was quick to ensure that a bill, which pledged to give taxpayer-funded financial support to “teachers of Christian religion,” was defeated. Over the following years, Madison spearheaded a movement that pushed for changes to the Articles of Confederation. That effort eventually culminated in the Constitutional Convention of 1787, again in Philadelphia.

At the convention, Madison presented his plans for an effective government known as the “Virginia Plan.” Madison noted that the United States needed a strong federal government, which should be split into three branches (the legislative, judicial and executive) and managed with a system of checks and balances, so that no branch could dominate another. Throughout the Constitutional Congress, Madison took extensive notes and tweaked his plan to make it more acceptable. In the end, the Virginia Plan underpinned large parts of the U.S. Constitution.

After the Constitution was written, the document needed to be ratified by nine out of the thirteen states. Initially, the document was met with resistance, as many states believed that it gave too much power to the federal government. In order to promote the Constitution’s ratification, Madison collaborated with Founding Fathers Alexander Hamilton and John Jay. Together, they wrote a series of anonymous essays supporting the Constitution, titled the Federalist Papers.

After the publication of 85 essays and extensive debate in the Constitutional Convention, the U.S. Constitution was signed in September 1787. The document was eventually ratified in 1788, after New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify the Constitution. In 1790, the new federal government became functional. The innovative and enlightened ideas of the U.S. Constitution have stood up to the test of time, and today it is the world’s oldest written constitution still in operation.

Madison was immediately elected to the newly formed House of Representatives and began working on a draft of the Bill of Rights – a list of 10 amendments to the Constitution that spelled out the fundamental rights held by every U.S. citizen. They included, among others, freedom of speech, religion and the right to bear arms. In the Ninth Amendment, Madison also stipulated the existence of unenumerated rights. After a substantial debate, Madison’s work paid off and the Bill of Rights was enacted into law in 1791. These amendments were unique for their time, for they stipulated that governments do not grant rights to the citizenry. Instead, it is the citizens who grant powers to governments to protect the people’s “pre-existing” rights.

After a disagreement with the Federalist leader, Alexander Hamilton, over Hamilton’s proposal to establish a national bank, Jefferson and Madison founded the Democratic-Republican party in 1792. It was the first opposition political party in the United States. Madison left Congress in 1797. He returned to frontline politics in 1801, joining President Thomas Jefferson’s cabinet. As secretary of state, Madison oversaw the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803, which doubled the size of the new nation.

Between 1809 and 1817, Madison served as the fourth president of the United States. Much of his presidency was marred by overseas problems. In 1812, Madison issued a war proclamation against Great Britain. Trade between the United States and Europe ceased, which severely hurt American merchants. At the same time, New England threatened to secede from the Union. Madison was forced to flee the new capital of Washington in August 1814, after the British troops invaded and burned down several buildings, including the White House, the Capitol and the Library of Congress.

In 1815, the war ended in a stalemate. After two terms as president, Madison returned to Montpelier in 1817 and never left Virginia again. He remained an active and respected writer. In 1826, he became a rector of the University of Virginia, which was founded by Thomas Jefferson in 1819.

Like many of his contemporaries in the South, Madison owned slaves. That said, Madison worked to abolish the practice of slavery. Under his leadership, the federal government purchased slaves from slaveholders and resettled them in Liberia. Madison’s last years were spent sickly and bed-bound. In June 1836, he died from heart failure. He was 85 years old.

Madison was instrumental to the drafting of the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights. The U.S. Constitution was the world’s first single-document constitution. The Enlightenment principles of individual rights and freedom that it championed became the basis for dozens of other liberal constitutions created by governments across the world. For creating the legal framework that protected countless people from government abuses, James Madison is deservedly our 44th Hero of Progress.