Today marks the 31st installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org titled Heroes of Progress. This bi-weekly column provides a short introduction to heroes who have made an extraordinary contribution to the well-being of humanity. You can find the 30th part of this series here.

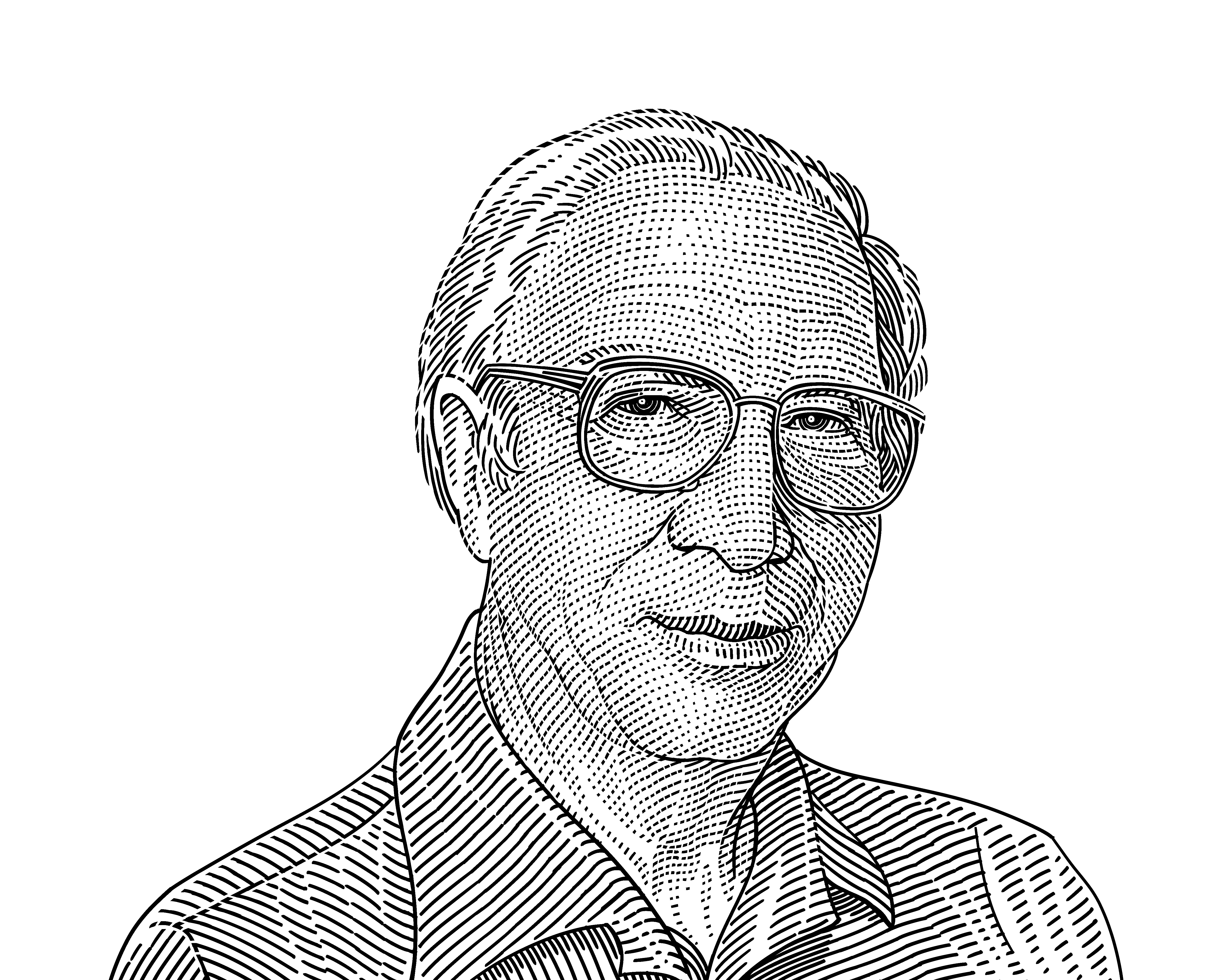

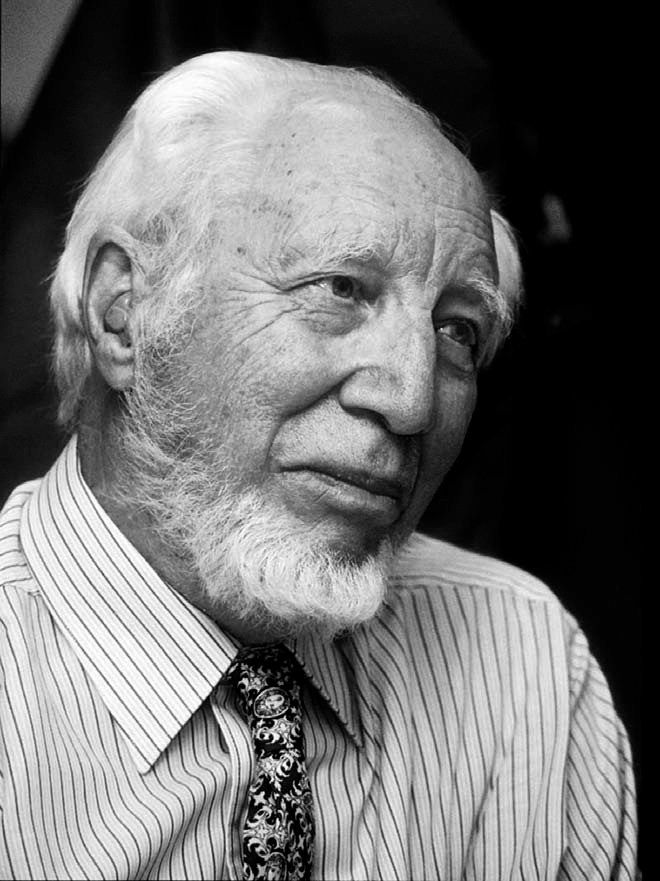

This week our hero is Willem Kolff, a Dutch physician who invented the world’s first kidney dialysis machine. Kolff also played an instrumental role in developing the world’s first artificial heart and, later, the first artificial eye. The World Economic Forum has estimated that since its invention, Kolff’s kidney dialysis machine, or what he liked to call “the artificial kidney,” has saved more than 9 million lives.

Willem Kolff was born on February 14, 1911, in Leiden, the Netherlands, into an old Dutch patrician family. Kolff suffered from dyslexia, but as the condition was not recognized at the time, as a child Kolff was often punished in school for the difficulties he had reading and spelling. Initially, Kolff wanted to become the director of a zoo, but after his father pointed out that career path had very limited job opportunities as there were just three zoos in the Netherlands at the time, Kolff decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and pursue a medical career.

Kolff began studying medicine at the University of Leiden in 1936 and was awarded a M.D. in 1938. Later that year, Kolff began studying for a PhD at the University of Groningen, while also working as an assistant in the university’s medical department.

On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. During the invasion Kolff was coincidentally attending a funeral in The Hague. Kolff decided to leave the funeral early and head to the city’s main hospital, which was already overwhelmed with casualties, to ask to set up what would be Europe’s first blood bank. The hospital agreed and Kolff was provided with a car. Kolff drove through the city collecting tubes, bottles, needles, citrate, and other paraphernalia – all while dodging sniper fire and avoiding falling bombs. Four days later the blood bank at The Hauge’s main hospital was operational and saved the lives of hundreds of people.

A month after Germany’s invasion, Kolff’s Jewish mentor in a Groningen hospital committed suicide and was replaced by a Nazi official. Kolff, not wanting to work with the Nazi, transfered to a small hospital in Kampen for the remainder of the war. It was also during the war that he concealed a Jewish colleague’s young son from the Nazis in his home.

When Kolff was a young physician, he witnessed the painful death of a 22-year-old patient who died of kidney failure. At the time, Kolff could do nothing to save the young man, but it struck him that if he had been able to remove the urea (the waste that healthy kidneys usually filter away), then the patient might have lived. Kolff noted, “I realized that removing 22 cubic centimetres of toxicity from his blood would have saved his life.” After that traumatic experience Kolff devoted himself to the research of kidney failure.

Kolff developed his first prototype kidney dialyzer machine in 1943. As the Netherlands was still under German occupation, materials were in short supply but Kolff managed to build his machine using orange juice cans, used auto parts, and cellophane sausage skins wrapped around a cylinder which rested in an enamel bath of cleansing fluid. Kolff’s machine drew the blood of a patient into a bath, cleaned it, and then passed it back into the patient’s body. Over a two-year period Kolff attempted to treat 15 patients with the machine but all attempts were unsuccessful. Despite the loss of life, Kolff persisted.

A breakthrough arrived a month after the war ended in August 1945, when Kolff treated a 65-year-old woman imprisoned for being a Nazi collaborator and in a coma due to renal failure. Many of his fellow countrymen disapproved of treating the woman due to her Nazi ties, but Kolff persisted in his Hippocratic duty and after hours of treatment, the woman awoke and went on to live for another 6 years before dying of causes unrelated to her kidney problems. A year later, in 1946, Kolff was awarded his PhD from the University of Groningen.

After proving the success of his artificial kidney, Kolff made dialysis machines and sent them to hospitals all over the world. The machines quickly gained popularity and in 1948, the artificial kidney was used to perform the first human dialysis in the United States, at the Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City.

Kolff immigrated to the United States in 1950 and joined the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. During his time in Cleveland, Kolff helped develop the first heart-lung machines which oxygenated blood, and maintained the heart and pulmonary functions of a patient during cardiac surgery. In 1967, Kolff became head of the University of Utah’s Division of Artificial Organs and Institute for Biomedical Engineering. While at Utah, Kolff led the medical team that developed the world’s first artificial heart, which was successfully implanted into a patient in December 1982.

Even though Kolff officially retired in 1986, he continued to work as a research professor and director of the Kolff Laboratory at the University of Utah until 1997. Throughout his life, Kolff was awarded more than 12 honorary doctorates from universities all over the world, and more than 120 international awards, including: the AMA Scientific Achievement Award in 1982, the Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research in 2002, and the Russ Prize in 2003. In 1990, Life Magazine listed Kolff as one of the 100 Most Important Persons of the 20th Century. Kolff died on February 11, 2009, just three days short of his 98th birthday.

Willem Kolff is often dubbed the “Father of Artificial Organs” and technology he created has saved millions of lives around the world. For that reason, Willem Kolff is our 31st Hero of Progress.