Today marks the 14th installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org titled, Heroes of Progress. This bi-weekly column provides a short introduction to heroes who have made an extraordinary contribution to the wellbeing of humanity. You can find the 13th part of this series here.

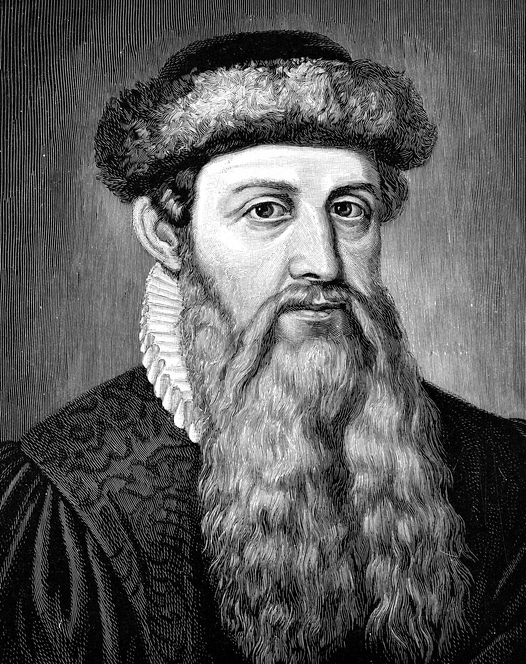

Our 14th Hero of Progress is Johannes Gutenberg, a 15th century German goldsmith and inventor, who created the first metal movable-type printing press. Gutenberg’s inventions inlcuded a process for mass-producing movable type, the use of oil-based ink for printing books, adjustable molds, mechanical movable type and the use of a wooden printing press similar to the agricultural screw presses of that time.

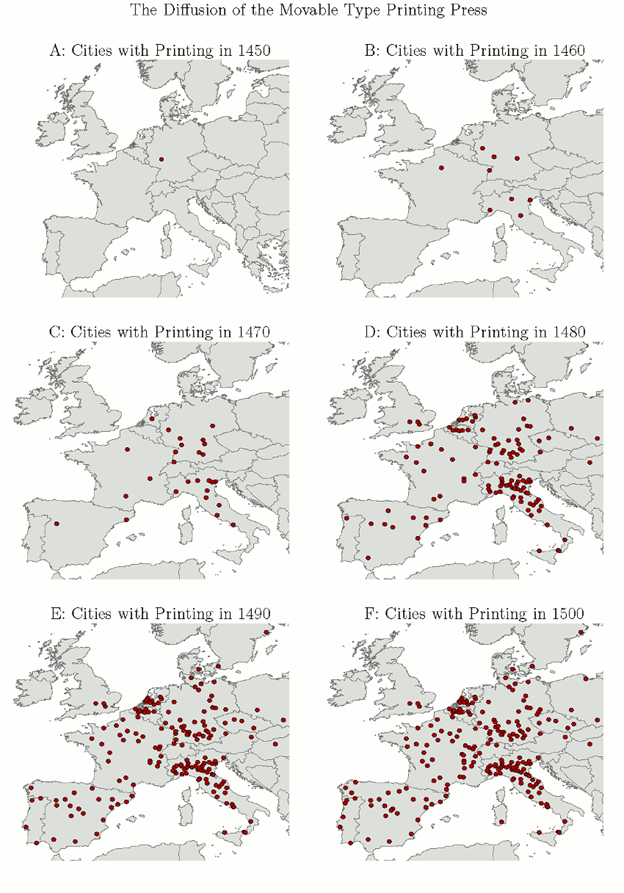

Gutenberg’s ideas started a printing revolution, which greatly improved the spread of information. The printing press helped to fuel the later part of the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Scientific Revolution, thus setting the stage for the start of the Industrial Revolution in the second half of the 18th century.

Relatively little is known about Gutenberg’s early life. It is believed he was born sometime between 1394 and 1404 in the city of Mainz, the Holy Roman Empire (today’s Germany). We do know that Gutenberg was born into a wealthy patrician merchant family and he grew up learning the trade of goldsmithing.

In 1411, the Gutenbergs were exiled from Mainz following an uprising against the patrician class. We don’t know much about Gutenberg’s life over the following fifteen years, but a letter written by him in 1434 indicates he was living in Strasbourg (today’s France). Moreover, legal records from that same year indicate that he was a goldsmith and a member of the Strasbourg militia.

Whilst in Strasbourg, Gutenberg created metal hand mirrors that pilgrims bought and used when visiting holy sites (it was thought hand mirrors could capture the holy light from religious relics). Gutenberg’s metal working skills proved useful when he developed the metal movable-type used in the printing press.

In 1439, Gutenberg encountered financial problems. Unable to placate his investors, Gutenberg is said to have shared a “secret” with them. It is speculated that the secret was a much-improved process of printing. A year later, Gutenberg supposedly declared that he had perfected the art of printing. That said, a workable prototype of his printing press remained a long way off.

In 1448, Gutenberg moved back to Mainz. With the help of a loan from his brother-in-law, Arnold Gelthus, he was able to build an operating printing press in 1450. A working press enabled Gutenberg to convince Johann Fust, a wealthy moneylender, to lend him more capital to fund further refinement of the printing process. Peter Schöffer, Fust’s son-in-law, also joined the enterprise and it is likely that Schöffer designed some of the press’ first typefaces.

It is widely accepted that Gutenberg had two presses, one for lucrative commercial texts, and another reserved for printing the Bible. In 1455, the first 180 copies of The Gutenberg Bible were completed. However, in the same year, Fust sued Gutenberg and demanded his money back, accusing Gutenberg of the misallocation of funds. The court ruled in favor of Fust, which gave him possession of the printing workshop and half of all the printed Bibles.

The court’s ruling left Gutenberg effectively bankrupt. Undeterred, Guttenberg managed to open a small printing shop in Bamberg (Bavaria) in 1459, where he continued printing Bibles. In 1465, Prince Archbishop of Mainz recognized Gutenberg’s accomplishments by naming him a Hofmann or a gentleman of the court. That meant that until his death in 1468, Gutenberg could live comfortably on the court’s large annual stipend.

Gutenberg’s innovation quickly spread throughout Europe and beyond. That meant that books and pamphlets became much cheaper and more easily accessible. The deluge of printed texts helped to increase literacy rates throughout the continent. Medical, scientific and technical knowledge proliferated, improving the lives of millions. Philosophical, religious and political treatises abounded. The monopolistic controls that guilds and nobility held over Europe’s economic and social life for centuries were broken. It is for those reasons that Johannes Gutenberg is our 14th Hero of Progress.