Last Friday, Botswana celebrated 50 years of independence. The former Bechuanaland Protectorate gained independence from Great Britain on September 30, 1966 and has thrived ever since. In far too many African countries, “Independence Day” has been a cause for lamentation, not celebration. Regrettably, African independence came at the worst possible moment. The 1960s was a decade when many Western countries seemed to have suffered a collective mental breakdown. In contrast, the USSR seemed to be doing rather well. The Soviets eclipsed the United States in the Space Race and, following the Cuban Revolution, communism gained a permanent foothold in the Americas. Appalled by the injustices of the colonial rule—and ignoring some of its benefits—Africans cast away the European yoke along with some of its more beneficial features: representative democracy, property rights, rule of law, free enterprise, and international trade. Understandably, but catastrophically, many African countries opted for the opposite of what the West had to offer and embraced socialism instead.

Not so with Botswana—a country that has been politically and economically freer than the rest of Africa for much of the last half-century. Why? Seretse Khama, the first president, was a tribal chief who maintained the tradition of public meetings, or kgotlas. Kgotlas were the traditional way in which Africans made local decisions. It was a good way in which to keep the chiefs honest and accountable. When I visited the country in 2007, a game warden I spoke to in the Chobe National Park reminisced about standing behind the minister of education in the line for groceries. A shop manager recognized the minister and motioned her to the front of the line. The minister flatly refused. The exceptional humility of Botswana’s politicians is just one positive consequence of such “grassroots democracy.”

Khama’s economics were also out of step with the times. He maintained a relatively “hands-off” approach to the economy, which was, for decades, the freest in Africa. Personally, I think that Khama, in addition to being a highly educated man (he was a graduate of Balliol College, Oxford) was prevented from economic experimentation by geopolitical necessity. Back then, Botswana was surrounded by the immensely powerful South Africa in the south, South Africa–dominated South West Africa in the west, and Rhodesia in the east. Neither government would have tolerated a Marxist state in its midst. And so Khama did a couple of sensible things—he kept the market economy he inherited and did not even bother to waste money on an independent military. Today, the prosperity and stability of Botswana is a testament to his enlightened leadership.

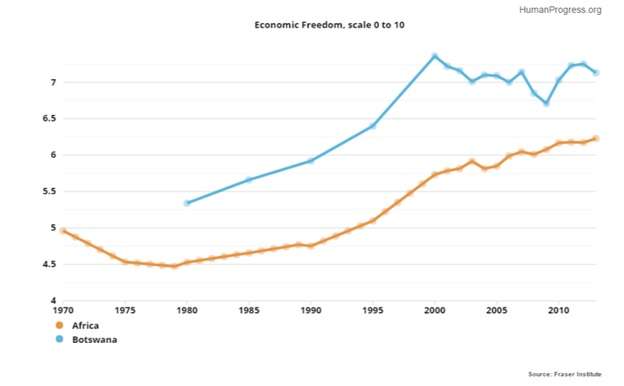

Economic freedom in Bostwana has constistently been higher than the African average.

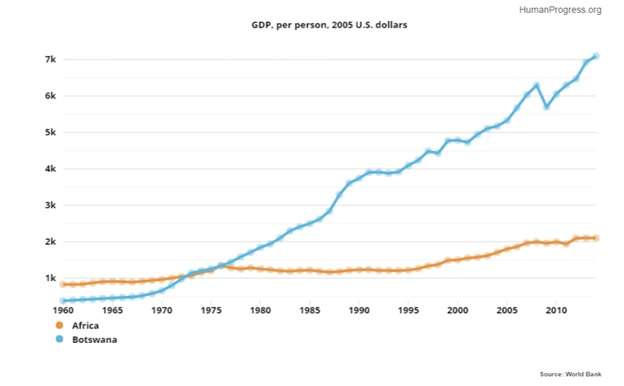

Thanks to this higher economic freedom, Botswana’s per-person GDP has increased rapidly. It passed the African average in the mid-1970s and has made steady progress since.

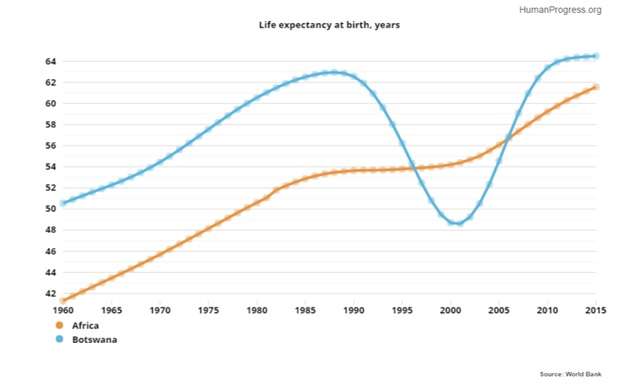

Botswana’s life expectancy quickly recovered from the HIV/AIDS epidemic, rising to retake its place above the continental average.

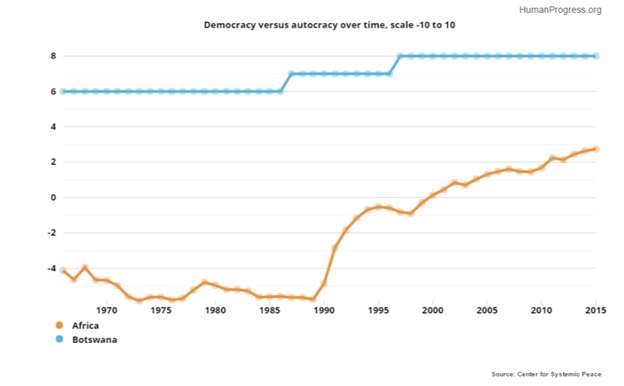

While autocracy mired many of its African neighbors, Botswana maintained a relatively high level of democracy for the continent.

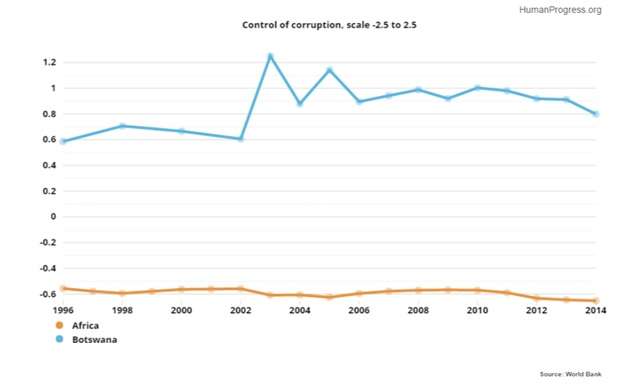

Botswana has managed to control corruption within its borders better than Africa as a whole.

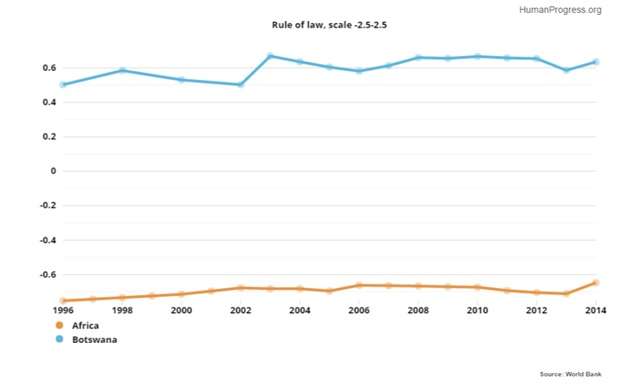

Enabling much of this progress, Botswana’s rule of law has also exceeded Africa’s for decades.

This article originally appeared in Reason.