Trying to imagine the past might conjure an image of an idyllic country village with pristine air and residents merrily dancing around maypoles. The healthy, peaceful, prosperous people in this fantasy of pastoral bliss do not realize their contented, leisurely lives will soon be disrupted by the story’s villain: the dark smokestacks of the Industrial Revolution. In this version of history, the terrible mistake of industrialization introduced pollution, disease, violence, and poverty into the world and forever banished mankind from the paradise of preindustrial existence.

If only one could return to the good old days!

Except that such rose-colored views of the past bear no resemblance to reality. The world our ancestors faced was in fact more gruesome than modern minds can fathom. Let’s deromanticize the past.

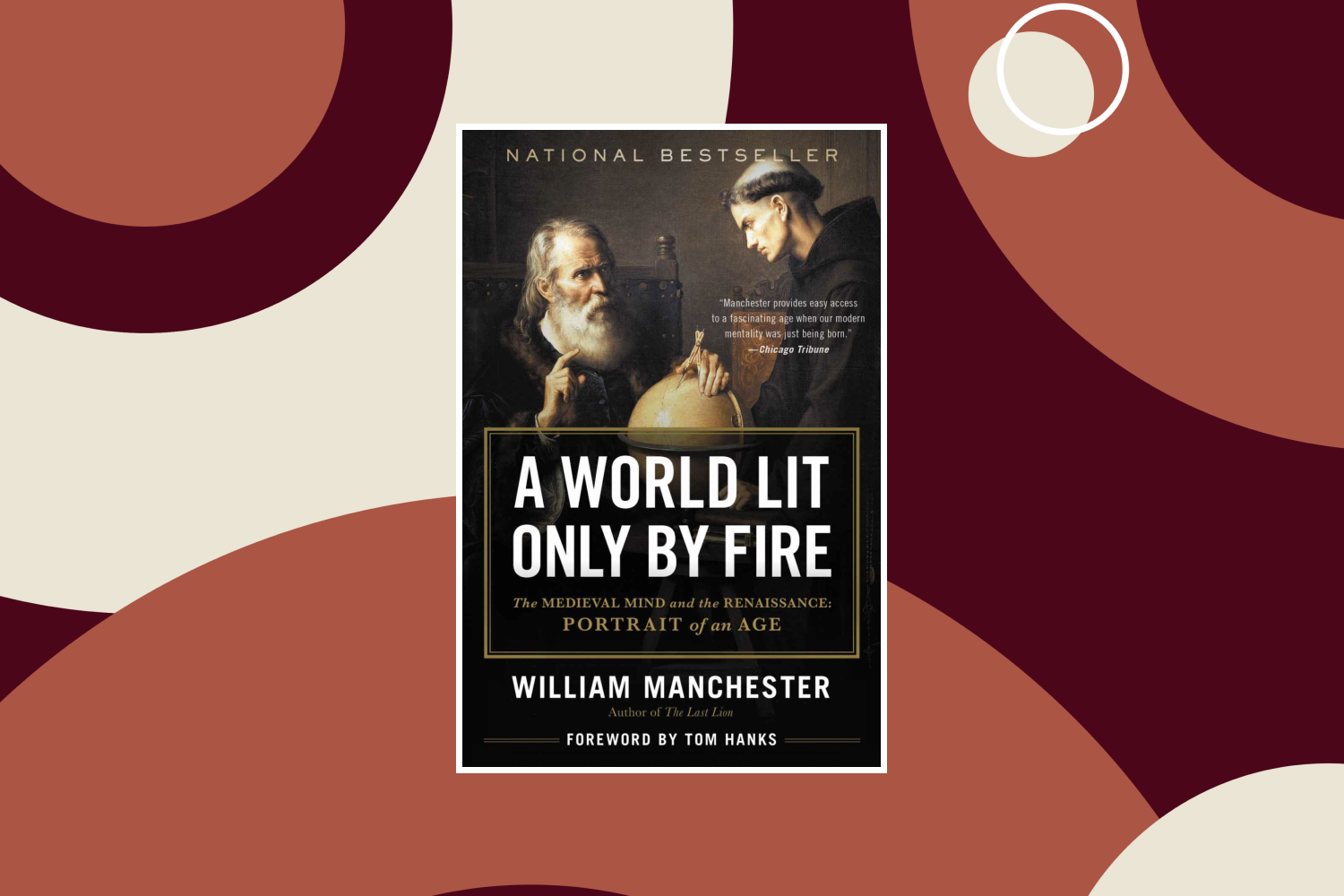

The late historian William Manchester’s bleak bestseller A World Lit Only by Fire: The Medieval Mind and the Renaissance: Portrait of an Age presents vivid examples of just how difficult everyday life in the past really was. First published in 1992, this book offers a sweeping, unflinching history of medieval and Renaissance Europe. While at times Manchester focused on the antics of history’s famous figures and their epic power struggles, his book also offers insights on the ordinary and unremarkable details that arguably defined our ancestors’ lives more than the grand events that history cares to remember. Here are some of the ugly highlights.

Most people lived in the countryside, where poverty was extreme and privacy was nonexistent:

“Between 80 and 90 percent of the population … lived in villages of fewer than a hundred people, fifteen or twenty miles apart, surrounded by endless woodlands.” Peasants “married fellow villagers and were so insular that local dialects were often incomprehensible to men living only a few miles away.” “Each hamlet was inbred, isolated, unaware of the world beyond the most familiar local landmark: a creek, or mill, or tall tree scarred by lightning.” “A visitor from the twentieth century would find their homes uncomfortable: damp, cold, and reeking from primitive sanitation, for plumbing was unknown.”

[T]he home of a prosperous peasant lacked [most] amenities. Lying at the end of a narrow, muddy lane, his rambling edifice of thatch, wattles, mud, and dirty brown wood was almost obscured by a towering dung heap in what, without it, would have been the front yard. The building was large, for it was more than a dwelling. Beneath its sagging roof were a pig pen, a henhouse, cattle sheds, corncribs, straw and hay, and, last and least, the family’s apartment, actually a single room whose walls and timbers were coated with soot. According to Erasmus, who examined such huts, ‘almost all the floors are of clay and rushes from the marshes, so carelessly renewed that the foundation sometimes remains for twenty years, harboring, there below, spittle and vomit and wine of dogs and men, beer … remnants of fishes, and other filth unnameable. Hence, with the change of weather, a vapor exhales which in my judgment is far from wholesome.’ The centerpiece of the room was a gigantic bedstead, piled high with straw pallets, all seething with vermin. Everyone slept there, regardless of age or gender—grandparents, parents, children, grandchildren, and hens and pigs—and if a couple chose to enjoy intimacy, the others were aware of every movement.

Poorer peasants lived in even worse circumstances:

Such families envied those enjoying greater comfort, and most of all they coveted their beds. They themselves slept on thin straw pallets covered by ragged blankets. Some were without blankets. Some didn’t even have pallets. If this familial situation seems primitive, it should be borne in mind that these were prosperous peasants. Not all their neighbors were so lucky. Some lived in tiny cabins of crossed laths stuffed with grass or straw, inadequately shielded from rain, snow, and wind. They lacked even a chimney; smoke from the cabin’s fire left through a small hole in the thatched roof—where, unsurprisingly, fires frequently broke out. These homes were without glass windows or shutters; in a storm, or in frigid weather, openings in the walls could only be stuffed with straw, rags—whatever was handy. Such families envied those enjoying greater comfort, and most of all they coveted their beds. They themselves slept on thin straw pallets covered by ragged blankets. Some were without blankets. Some didn’t even have pallets.

The cities weren’t that much better:

The twisting streets were as narrow as the breadth of a man’s shoulders, and pedestrians bore bruises from collisions with one another. There was no paving; shops opened directly on the streets, which were filthy; excrement, urine, and offal were simply flung out windows. And it was easy to get lost. Sunlight rarely reached ground level, because the second story of each building always jutted out over the first, the third over the second, and the fourth and fifth stories over those lower. At the top burghers could actually shake hands with neighbors across the way. Rain rarely fell on pedestrians, for which they were grateful, and little air or light, for which they weren’t.

People were so hungry that they sometimes resorted to cannibalism, and when they did have enough to eat they apparently often engaged in violent spousal abuse at the dinner table. Also, malnourishment and heavy drinking seem to have stunted growth and kept the population extremely short.

Typically, three years of harvests could be expected for one year of famine. The years of hunger were terrible. The peasants might be forced to sell all they owned, including their pitifully inadequate clothing, and be reduced to nudity in all seasons. In hardest times they devoured bark, roots, grass; even white clay. Cannibalism was not unknown. Strangers and travelers were waylaid and killed to be eaten, and there are tales of gallows being torn down—as many as twenty bodies would hang from a single scaffold—by men frantic to eat the warm flesh raw.

In all classes, table manners were atrocious. Men behaved like boors at meals. They customarily ate with their hats on and frequently beat their wives at table, while chewing a sausage or gnawing at a bone … According to Erasmus, decorum dictated that food be brought to the mouth with one’s fingers.

The average man stood a few inches over five feet and weighed about 135 pounds. His wife was shorter and lighter. Anyone standing several inches over six feet was considered a giant and inspired legends.

Hygiene was nightmarish, as were labor conditions:

Their clothes and their bodies were filthy. The story was often told of the peasant in the city who, passing a lane of perfume shops, fainted at the unfamiliar scent and was revived by holding a shovel of excrement under his nose.

Since few Europeans possessed a change of clothes, the same raiment was worn daily; as a consequence, skin diseases were astonishingly prevalent.

Peasants labored harder, sweated more, and collapsed from exhaustion more often than their animals.

[T]hey worked—entire families, including expectant mothers and toddlers in the fields and pastures between their huts and the great forest. It was brutish toil … Wheat had to be beaten out by flails.

Medicine also left much to be desired.

Doctors diagnosing illnesses were influenced by the constellation under which the patient had been born or taken sick; thus the eminent surgeon Guy de Chauliac wrote: “If anyone is wounded in the neck when the moon is at Taurus, the affliction will be dangerous.”

One document from the [medieval] period is a calendar, published at Mainz, which designates the best astrological times for bloodletting. Epidemics were attributed to unfortunate configurations of the stars.

People didn’t live long and also aged prematurely. Women lived even shorter lives than men due to an astronomical rate of death in childbirth:

Richard Rolle had written earlier, that “few men now reach the age of forty, and fewer still the age of fifty.” If a man passed that milestone, his chances of reaching his late forties or his early fifties were good, though he looked much older; at forty-five his hair was as white, back as bent, and face as knurled as an octogenarian’s today. The same was true of his wife—”Old Gretel,” a woman in her thirties might be called. In longevity she was less fortunate than her husband. The toll at childbirth was appalling. A young girl’s life expectancy was twenty-four. On her wedding day, traditionally, her mother gave her a piece of fine cloth which could be made into a frock. Six or seven years later it would become her shroud.

Another cause of untimely deaths was the Black Death pandemic.

“The mounting toll of disease—each night gravediggers’ carts creaked down streets as drivers cried, ‘Bring out your dead!’ and in Germany entire towns, a chronicler of the time wrote, had become like cemeteries ‘in ihrer betru benden Einsamkeit’ (‘in their sad desertion’)—was” a prominent feature of life in the medieval period.

People had some strange beliefs—and took action to try to keep the deceased from transforming into vampires.

They believed in sorcery, witchcraft, hobgoblins, werewolves, amulets, and black magic … If a lady died, the instant her breath stopped servants ran through the manor house, emptying every container of water to prevent her soul from drowning, and before her funeral the corpse was carefully watched to prevent any dog or cat from running across the coffin, thus changing her remains to a vampire … If a man donned a clean white shirt on a Friday, or saw a shooting star, or a will-o’-the-wisp in the marshes, or a vulture hovering over his home, his death was very near. Similarly, a woman stupid enough to wash clothes at Holy Week would soon be in her grave. Should thirteen people be so thoughtless as to sup at one table, one of those present would not be there for tomorrow morning’s meal; if a wolf howled in the night, one who heard him would disappear before dawn. Comets and eclipses were sinister. Everyone knew that an enormous comet had been sighted in July 1198 and Richard the Lion-Hearted had died ‘very soon after.’ (In fact he did not die until April 6, 1199.) Everyone also knew—and every child was taught that [there were] ghouls who snuffled out cadavers in graveyards and chewed their bones, water nymphs skilled at luring knights to death by drowning, dracs who carried little children off to their caves beneath the earth, wolfmen—the undead turned into ravenous beasts—and vampires who rose from their tombs at dusk to suck the blood of men, women, or children who had strayed from home.

Scholars as eminent as Erasmus and Sir Thomas More accepted the existence of witchcraft.

Speaking of Erasmus, confused as he may have been regarding witchcraft, the world is better for his championing of religious toleration—because intolerance can have lethal results. Manchester describes how during Europe’s wars of religion, Catholics and Protestants murdered one another with gusto. Perhaps the most shocking part was that despite the radical amount of killing happening, demand for public executions outstripped supply. As hard as it may be to comprehend, life was so boring and compassion so wanting that for many people the bloodbath was a source of entertainment.

Autos-da-fé were more popular than ever. Peasants would walk thirty miles to hoot and jeer as a fellow Christian, enveloped in flames, writhed and screamed his life away. Afterward the most ardent spectators could be identified by their own singed hair and features; in their eagerness to enjoy the gamy scent of burning flesh, they had crowded too close. Ultimately this fascination with death, as ordinary then as it seems extraordinary now, led to massive butchery.

A Protestant council sentenced [Michael Servetus, a Catholic theologian] to death by slow fire … He begged for mercy—not for his life … he merely wanted to be beheaded. He was denied it. Instead he was burned alive. It took him half an hour to die. The Catholics who quartered the body of the Swiss [Protestant theologian] Huldrych Zwingli and burned it on a pyre of dried excrement were equally merciless.

A suspect was arrested. No evidence was produced, but he was tortured day and night for a month till he confessed. Screaming with pain, he was lashed to a wooden stake. Penultimately, his feet were nailed to the wood; ultimately he was decapitated. [Protestant theologian John] Calvin’s justification for this excessive rebuke reveals the mind of all Reformation inquisitors, Protestant and Catholic alike.