Trying to imagine life in the colonies that became the United States might conjure an image of colonists cheerfully dancing to fife music, reveling in the land of peace and plenty where they have recently settled.

If only one could return to the good old days!

Except that such rose-colored views of the past bear no resemblance to reality. The world our ancestors faced was in fact more gruesome than modern minds can fathom. Let’s deromanticize the past.

Everyday Life in Colonial America, by the late scholar and defender of private philanthropy Louis Booker Wright, presents detailed examples of just how difficult everyday life in the past really was. First published in 1965, this book offers a glimpse into a world where there was “no leisure time as we know it, no labor-saving devices, no radio, no means for rapid transportation or communication.” Wright’s portrait of the colonists’ day-to-day struggles reveals dire poverty, shocking violence, and unending work. Here are some of the grisly highlights.

Colonial medicine was sometimes actively harmful, for example advising consumption of toxic plants. A Spanish physician named Nicolás Monardes (1493–1588) wrote a book that remained popular in its English translation for centuries. Joyful News Out of the New World (1577) described, among other things, supposedly wondrous medicines growing from the earth throughout America.

Of all the medicinal herbs that Monardes described, tobacco treated the widest range of ailments. He reported that it was good for headache, toothache, rheumatism, pains in the joints, stomachaches of every kind, chilblains, swellings of all kinds, wounds of every description, snake bite, and even bad breath. Tobacco could be smoked, chewed, made into poultices, powdered and rubbed into wounds, steeped as a tea, and rolled into pills. For nearly two centuries after the publication of this book, many people believed tobacco was a remedy for various ailments … [And] most writers praised tobacco’s curative powers.

Among other products that Monardes recommended was sassafras, which, he declared, would cure even more diseases than tobacco … In Europe the demand for sassafras was for a time insatiable, as everyone turned to sassafras tea as a panacea for ache and pain.

“Tobacco and sassafras, the first universal wonder drugs,” were both, in fact, highly damaging to the human body.

When the colonists weren’t poisoning themselves with quack remedies, they were working. Work was endless.

The amount of human toil required to establish themselves is hard for us even to imagine today.

To find enough cleared land for crops was one of the colonists’ most difficult problems. The labor of cutting down and removing trees in a heavily forested area is enormous, even with power tools, and the colonists in the early years did not have even a horse or an ox to drag the trees away.

The only power other than that of human brawn was supplied by a horse, mule, or ox. The first plows in America showed little improvement over those used in the Middle Ages.

Nobody in the colonial period ever heard of an eight hour day. The workday on the farm was from sun to sun, sunup until sundown. Indeed, it was often longer than this, for livestock had to be fed and cows milked by lantern light in winter; even in the summer the farmer and his family were usually up and about their work long before sunrise.

Almost every farmer’s wife had a spinning wheel and many a farmer worked at a loom during the winter when little work could be done outdoors.

[E]verybody was so busy with the struggle for the raw essentials of life that there was no time for formal entertainment. … They had enough to do to stay alive.

Women least of all knew the luxury of leisure. A common proverb ran, “Man works from sun to sun, but woman’s work is never done.” That was literally true. … [S]he had to cook and wash for the whole family without benefit of any labor-saving device; she not only had to make garments for all the family, including the menfolk, but she had to spin the thread and weave the yarn into the cloth for these garments. Her hands could never be idle … She did not have time to worry about amusements, though she did manage at times to find pleasure in such communal activities as quilting parties. Pleasure in the colonial period, both for women and men, frequently had to be found in some essential activity.

One such essential activity was slaughtering animals, such as pests and farm animals. The colonists were bored out of their minds and sometimes made a game of killing the animals, finding pleasure in lethally clubbing rats and torturing and decapitating geese with their bare hands.

A part of the talk about the fireside in the evening would be about how Old Brindle or some other animal had behaved that day. Since the weather, even in summer, was not invariably fair, there were days when it was too wet and rainy for much work out of doors. Such days were times for relaxation and fun … Sports on rainy days were simple and sometimes crude. Boys frequently organized rat killings, which provided a certain amount of excitement. A group armed with clubs gathered around a pile of corn in the corncrib and slowly pitched the ears into a new pile. As the old pile dwindled, the rats harboring there ran out, to be clubbed to death on the crib floor. The boy with the largest number of rats to his credit was proclaimed champion rat killer. Sometimes wrestling matches would take place in the barns or corn cribs.

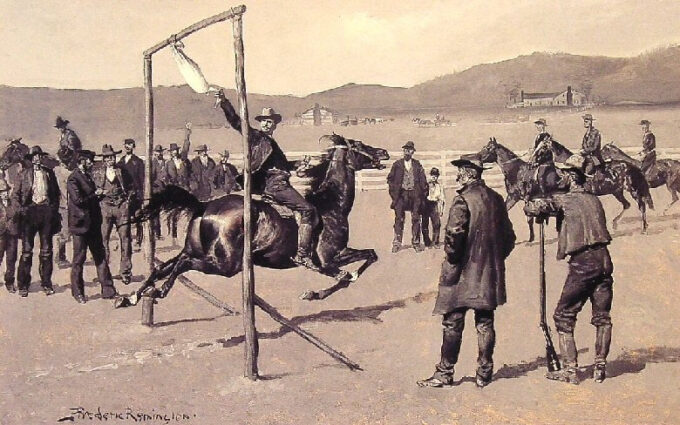

[Popular pastimes included] running after a greased pig or “gander pulling,” in which men rode by and tried to pull off the well-greased head of a goose suspended from a bar. When a rider lost his balance and tumbled to the ground, the crowd held their sides with laughter. Our ancestors were not overly refined and they did not worry about such things as pain to the goose or danger to the rider.

Gander pulling was most popular in the southern colonies. In Massachusetts, on the other hand, Puritans banned even innocent pastimes. There, “the General Court forbade both shuffleboard and bowling.” “Some towns made the sale of playing cards illegal.” Playing cards were called “the devil’s picture books.”

They also disapproved of the celebration of Christmas as “a wicked waste of time” and a sign of “popish superstition,” and Judge Samuel Sewall of Boston ordered shopkeepers to keep their stores open on the day. (The Puritan colonists did not tolerate different religions or creeds, particularly Catholicism). The Reverend John Cotton of Boston decreed that a girl should not draw a boy’s name out of a hat and write his name on a valentine card for Valentine’s Day.

Massachusetts also attempted to suppress so-called “lascivious dancing to wanton ditties” and any “mixed dancing” involving both male and female dancers. In the more liberal South, dancing was popular, although religious toleration was no better—one popular game at social gatherings was called “Break the Pope’s Neck.” Cockfighting was also extraordinarily popular: “cockfighting took place on all levels of society.” And while today wolves are the target of conservation efforts, the colonists enjoyed wolf-hunting:

In seventeenth-century New England wolves were a menace and a bounty was offered for wolf heads. Men and boys in the time that they could spare from routine tasks hunted wolves and brought in their heads to the magistrates of townships. It was the custom in many districts to hang wolf heads against the outside walls of the meetinghouse.

“Muster Day” drills also became a source of entertainment. Most colonial towns maintained a militia, as relations with indigenous tribes were poor and sporadic wars broke out. (King Philip’s War, for example, which took place from 1675 to 1678, killed “one [colonial] man in sixteen throughout New England.” After the war, Massachusetts “made death the penalty for evading military service.”) “At intervals, the militia, composed of all [male] able-bodied citizens of a certain age, had to be called together for drills.” Those occasions were called Muster Days. “Contests of marksmanship were usual … The targets might be live turkeys or ducks, for our ancestors were not squeamish.” It was common for an “impromptu wrestling match and fist fight” to break out:

If some of the crowd reeled home with broken heads and black eyes, that did not decrease the pleasure of others. Muster Day was an occasion no boy wanted to miss.

Perhaps the most violent pastime of all was their version of football:

Football was a rough-and-tumble scrimmage without the elaborate rules that we know today. One side, with any number of players, lined up against another and tried to push a ball through to the opposite side. Heads were bashed and noses bloodied and the game sometimes degenerated into a free-for-all fight. This type of football had been plated in England for generations and is supposed to have originated in primitive times, when opposing sides would fight for the head of a victim of a human sacrifice. At any rate, English writers of books of conduct, as well as New England preachers, condemned football as dangerous and liable to break the limbs and necks of the players.

As for tamer pastimes, many people enjoyed reading then just as today. But their libraries often consisted of “only a handful of books,” reread over and over.

Most know that many colonists enslaved people and treated those individuals as less than human, but the colonists even beat and tortured their non-enslaved servants, whose humanity they ostensibly recognized:

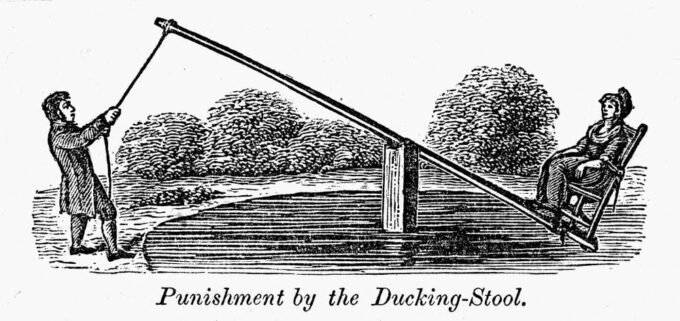

The authorities intervened only in cases of unusual severity, for beatings were considered normal. In 1666, Nicholas and Judith Weekes of Kittery, in what is now Maine, went too far, and caused the death of a servant. The wife confessed that she had cut off his toes. Occasionally the court intervened in the case of an unruly apprentice or servant. A Virginia jury in 1663, after considering a case of incorrigible impudence from a woman servant indentured to a master who could not control his household, ordered both servant and master to be ducked: she for impudence, he because he had “degenerated so much from a man as neither to bear rule over his woman servant or govern his house.”

Child labor was common. Like adults, children worked from sunup until sundown:

Children were bound out as apprentices when they were very young. Normally, boys served a master until they were twenty-one; girls served until they were from sixteen to eighteen, or until they married. It had not yet occurred to anyone that child labor was evil, and children were expected to work as early as they could manipulate the implements of labor. … Children as young as the six-year-old Isaiah Thomas were apprenticed by their parents, who signed the indentures.

In the case of orphans, town or county authorities had the right to bind them out at any age to masters who would look after them and bring them up in some trade or occupation.

Compared with modern concepts of working hours, leisure, holidays, and paid vacations, the life of a colonial apprentice was hard, monotonous, and dreary. He was expected to work from dawn to dusk and to keep busy in the evenings if duties in the household required it. He could not restrict his labor to any set number of hours per week, and if he had a respite on Saturday or a half day some other time he was more fortunate than most.

Children often received a rudimentary education. But school was far away, cold, and the teachers were violent.

Many a colonial child thought nothing of walking three or four miles to get to a village schoolhouse.

[T]eachers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries generally believed in exercising firm discipline enforced by a birch rod or a hickory switch kept in plain view to warn any would-be misbehaver of punishment in store. Not only were pupils soundly thrashed for disorderly behavior, but some teachers believed in ‘beating learning into them’ when they seemed negligent of their lessons.

Punishments were sometimes severe, and many a youngster went home with the marks of the switch upon his legs. Parents for the most part approved of this discipline and it was the rule in some households that a child received another beating for good measure when he got home to signify the parents’ approval of the punishment meted out at school. Beating was not the only punishment. In some New England schools parents were expected to help pay for the child’s education by supplying firewood; when parents failed to supply wood, their children were placed farthest from the fire in the coldest part of the room. A shivering child would be certain to carry the word home that wood was needed.

But at least the people of the colonial era enjoyed their pristine surroundings, those beautiful untouched forests, right? Think again.

No seventeenth-century settler ever wrote a poem on the beauty of the forests primeval.

Forests, which in many parts of the Atlantic seaboard extended almost to the edge of the sea, seemed not only mysterious and ominous to the first settlers but also hindered travel … Briers caught on a traveler’s clothes and tore his garments to shreds.

Great Britain had been improvident in the use of her own forests and lacked sufficient oaks to provide ship timbers and other lumber. So barren was Scotland of woods in the seventeenth century that someone remarked that Judas could have found salvation sooner than a tree on which to hang himself. The manufacture of iron and steel required charcoal, obtained from the burning of timber in kilns, and England needed charcoal. The mother country turned to the forests of America for all of these products.

So much for environmental stewardship in the old days. Today, in contrast, the U.K. has regained forest levels registered in the Domesday Book about a thousand years ago.