If you are a sci-fi fan, then you have probably noticed the dystopian character of movies about the future. From the classics, such as Soylent Green and Blade Runner, to modern hits, such as the Matrix trilogy and District 9, Hollywood’s take on the future is almost invariably negative. The story lines tend to centre on depletion of natural resources, like in the Mad Max movies, the emergence of highly stratified societies, like Elysium, or both.

In Hollywood’s rendition, the future consists of a few people at the top, who partake in the good life and enjoy what’s left of earth’s resources, while the much more numerous masses suffer some form of enslavement and destitution. That is, until one day, a messianic figure emerges to overthrow the existing order, slaughters the oppressors, liberates the untermenschen and ushers in an era of peace and prosperity.

One of the most recent installments in Hollywood’s ceaseless torrent of dystopianism is the widely popular Hunger Games franchise. The plot warns of the dangers of authoritarianism and of the utter failure of central planning. Thanks to capitalism, the future will look very different. Before we get to that, here is a quick summary of the plot.

The Hunger Games is a book trilogy by Suzanne Collins, consisting of The Hunger Games, Catching Fire and Mockingjay. These books were adapted into four popular movies, with the last book split into two feature films — Mockingjay Part I & II. The books sold more than 65 million copies in the United States alone, and have been translated into 51 different languages. In total, the movies made almost 3 billion dollars worldwide. In an NPR poll, The Hunger Games were second only to Harry Potter in popularity among teenagers. The three-finger salute used by the revolutionaries in The Hunger Games series became a real-life symbol of defiance in Thailand, where people were imprisoned for making the gesture.

The Hunger Games is set in what used to be the United States of America, but has transmogrified into an evil authoritarian regime called “Panem” (from Latin “panem et circenses,” or “bread and circuses”). In an extremely wealthy city located somewhere in the Rocky Mountains called the Capitol, the wealthy live impossibly lavish lives and rule over the surrounding districts. They wear elaborate make-up and bizarre modes of dress very loosely reminiscent of the opulence of French courtiers right before the French Revolution. They have constant parties with much pageantry and impressive technology (e.g., their food dispensers and showers have hundreds of buttons, etc.). At their parties, when they become full, they drink a liquid drug that causes them to vomit, so that they can enjoy more of the fine food that is available to them. Most do not produce anything and those who do “work” perform jobs like “TV host” or “fashion designer” – mainly for their own amusement.

Each of the twelve surrounding districts has a single centrally-planned economic specialization. Some districts are richer than others, but most are very poor. District 7’s people, for example, cut trees for lumber all day. The people in District 4 catch fish, while District 9 produces grain, District 10 raises livestock, and District 11 maintains orchards. The poorest district is District 12, located in Appalachia, whose people are coal miners and frequently starve. They are not allowed access to advanced technology, although they have old television sets to view government propaganda and the Hunger Games.

The people of the Capitol host a reality television show called the Hunger Games, where children from the different districts must battle each other. The children have to survive without food in a large forest-like domed arena filled with genetically engineered monsters, and kill each other as well as the monsters. The last child alive is set free to return to his or her district. The Capitol’s residents see no moral problem with the Hunger Games – the lives of the poor laborers’ children mean nothing to them.

Over the course of the series, a girl, Katniss, and boy, Peeta, from the poor Appalachian mining district manage to survive as contestants on the Hunger Games twice. That forms the plot of the first two books. In the last book, they become involved with a violent revolution against the ruling class in the Capitol. The boy, Peeta, is captured by the government and tortured, but the revolution eventually succeeds. The Hunger Games are abolished and a new government is installed. Katniss and Peeta survive the war, grow up, and eventually have children together.

If you are looking for drama and excitement as dished out by the talented Ms. Collins, feel free to watch all 548 minutes of the four movies combined. If, on the other hand, you are interested in taking a peak at the future as it is being currently created by ordinary human beings, watch this 2-minute video of a driverless tractor developed by Case IH, a manufacturer of agricultural equipment.

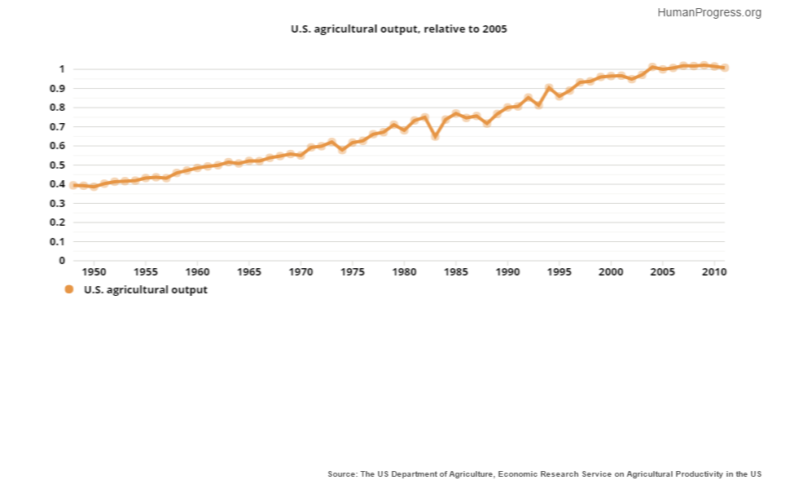

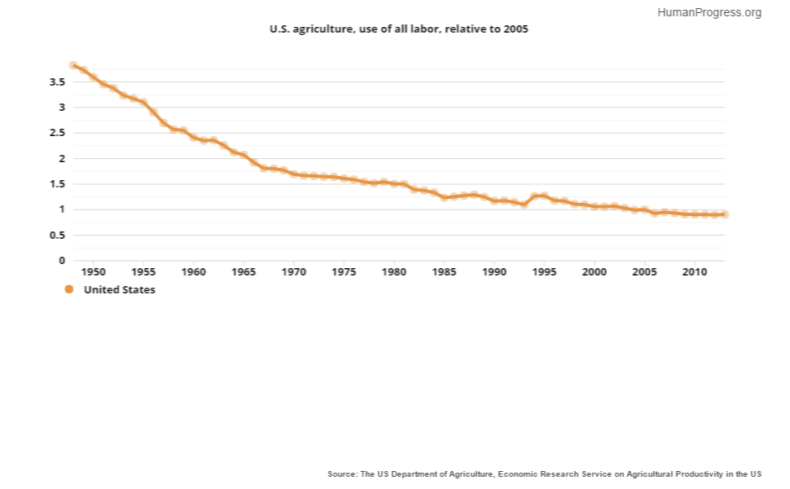

Chances are, fully autonomous robots will complete the process of mechanization of American farming in our lifetime. Already less than 2 percent of the American labor force works in agriculture – many as tractor and truck drivers, not manual laborers. This tiny fraction of American workforce produces enough food to feed not only the United States, but also, through American food exports, much of the rest of the world.

Put differently, feeding humanity does not require a permanent underclass of modern-day helots, as Hollywood would have you believe. Programmers and innovators in urban centers (i.e., the Capitol) compete with one another to produce labor-saving machines that make the lives of the people on farms (i.e., the districts) easier. Far from preventing the latter from acquiring new technology, the livelihoods of the former depend on the purchasing power of the farmers – who have higher incomes and more wealth than the American median.

Finally, consider agricultural productivity in the global context. As Professor Jesse H. Ausubel of the Rockefeller University writes, “agriculture has always been the greatest destroyer of nature, stripping and despoiling it, and reducing acreage left.” Thus, if humanity can further increase crop yields – since 1940, the American farmers have quintupled corn production while using the same or even less land – some of the agricultural land could be returned to nature.

Globally, therefore, adoption of American farming techniques could increase agricultural productivity so much that a landmass the size of India could be returned to nature, without compromising the food supply to our apparently “peaking” global population – the world’s population is likely to peak at 8.7 billion in 2055 and then start to decline. Last, but not least, tens of millions of agricultural laborers in Africa and Asia will be freed from back-breaking labor, migrate to the cities and create wealth in other ways.

If you are truly concerned about the future of humanity in general, and hunger, poverty and equality in particular, forget about The Hunger Games and embrace the driverless tractor instead.