On June 23, 2016, the British people voted in a referendum to leave the European Union. The shock on both sides of the English Channel was palpable and two schools of thought on the impending divorce between the U.K. and the EU have emerged.

The proponents of Brexit emphasize the benefits of free trade and continued (albeit inter-governmental and no longer supra-national) cooperation between the U.K. and the EU. They argue that an acrimonious divorce between the two would help neither party. Britain, they say, imports much more from the EU than the EU does from Britain, and a tariff war between the U.K. and the EU would not be in Europe’s interest. They also argue that Britain, being a part of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, is needed to counterbalance Russia. Britain’s European partners within NATO, therefore, have an incentive to keep the U.K. more-or-less happy.

The opponents of Brexit have warned that a vote in favor of the U.K.’s withdrawal from the EU would result in economic meltdown on the British Isles. Mercifully that has (so far) not come to pass, but that does not mean that Brexit negotiations will be plain sailing. The Eurocrats in Brussels, who will negotiate the terms of the British withdrawal from the EU, face their own set of incentives. Make the divorce between the EU and the U.K. too pleasant, they contend, and other EU countries may decide to follow the British example and leave the EU as well.

In the months that have followed the Brexit referendum, the two sides have been maneuvering to occupy the high ground once the actual negotiations on Brexit commence. (That should happen by the end of March 2017, when the British Prime Minister Theresa May is expected to trigger Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, which deals with a member country’s withdrawal from the EU.)

The British Chancellor of the Exchequer, Phillip Hammond, for example, let it be known that “Britain could transform its economic model into that of a corporate tax haven if the EU fails to provide it with an agreement on market access after Brexit.”

“I personally hope we will be able to remain in the mainstream of European economic and social thinking,” Hammond said, “but if we are forced to be something different, then we will have to become something different… We could be forced to change our economic model, and we will have to change our model to regain competitiveness. And you [Europeans] can be sure we will do whatever we have to do.”

The U.K. ministers, hope to “force EU leaders to give them a good Brexit deal by drafting legislation proving their threat to slash taxes is real. Ready-to-go Budgets will be drawn up cutting corporation tax and scrapping regulations if the negotiations are stalling… The move is designed to show those on the other side of the negotiating table that Britain is serious about becoming ‘the new Singapore’ unless trade barriers are kept low.” Why Singapore? Let’s look at a couple of statistics.

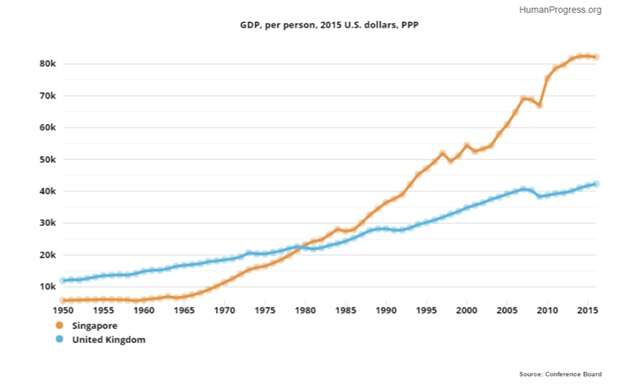

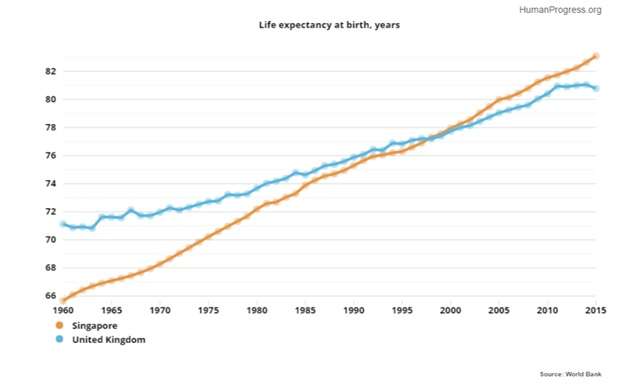

In 1950, GDP per capita adjusted for inflation and purchasing power parity was $5,689.91 in Singapore. It was $11,920.58 in the U.K. Average income in Singapore, in other words, amounted to 48 percent of that in the U.K. In 2016, income in Singapore was $82,168.33 and $42,287.17 in the U.K. Put differently, Singaporeans earned 94 percent more than the British. During the intervening years, Singaporean incomes rose by 1,344 percent, while British incomes rose by 256 percent. (A similar story could be told about life expectancy.)

Based on these two telling statistics alone, the “threat” of Singaporean tax rates and regulatory framework ought not to be a mere negotiating strategy for the British government vis-a-vis the EU. It ought to be a goal of the British decision makers—regardless of what the EU decides!

This article first appeared in Reason.