A wealthy Manhattan woman died after her clothes caught fire while cooking last week. Her tragic death was unusual, but there was a time when cooking was far more dangerous and time-consuming. Even today, more than 4 million people lacking modern stoves die prematurely each year from breathing in cooking fumes. Not only was cooking once unsafe, it left time for little else.

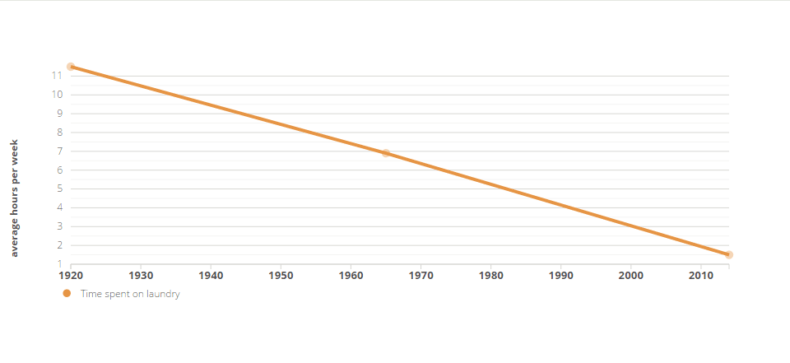

As Professor Deirdre McCloskey once noted, “[in] 1900 a typical American household of the middle class would spend 44 hours [a week] in food preparation,” and most of that work fell to women. In other words, back in the days of churning one’s own butter and baking one’s own bread, food preparation took up the same hours as a full-time job. That estimate includes time spent on purchasing, cooking and serving food as well as dishwashing. Keep in mind that in addition to cooking, women were also often responsible for cleaning the home, laundry, mending clothes, and tending to children.

Things started changing quickly. In 1910, U.S. households spent approximately six hours daily cooking meals, including cleanup; by the mid-1960s (when more reliable estimates began), that fell to one and a half hours. By 2008, the average low-income American spent just over an hour on food preparation each day and the average high-income American spent slightly less than an hour on food preparation daily. Disaggregating the data by gender reveals even more progress for women. In the United States, from the mid-1960s to 2008, women more than halved the amount of time they spent on food preparation (whereas men nearly doubled the time they spent on that activity, as household labor distributions became more equitable between the genders).

Mass production of everyday foodstuffs helped transform how women spent their time. In 1890, 90 percent of American women baked their own bread. Factory-baked, pre-sliced bread debuted in 1928. By 1965, 78 out of every 100 pounds of flour a U.S. woman brought into her kitchen came in the form of baked bread or some other ready-prepared good. Today, baking bread is an amusement for foodies, rather than a necessary chore for all women.

Over time, markets brought about and lowered the cost of such innovations as microwaves, convection ovens, ranges, grills, toasters, blenders, food processors, slow-cookers and other labor-saving kitchen devices. Markets have even produced grocery delivery services that bring food to one’s door with the touch of an application on a smartphone. Market processes also lowered the cost of dining out, and today Americans spend more dining out than eating in.

The liberation of women from the kitchen is ongoing, as technological devices and mass-produced goods spread to new parts of the world. Globally, as many as 55 percent of households still cook entirely from raw ingredients at least once a week. A 2015 survey found that average hours spent cooking among those who regularly cook are as high as 13.2 hours per week in India, and 8.3 in Indonesia, compared to 5.9 in the United States.

The gap in time spent on food preparation between rich and poor countries remains wide. But even in India — the poorest country surveyed, and the one with the highest reported average food preparation hours — women devote almost 31 fewer hours to food preparation per week than U.S. households did in 1900. Even allowing for compatibility problems when comparing those figures (the estimate for 1900 was for the household and included meal cleanup time), the sheer size of this difference suggests some improvement.

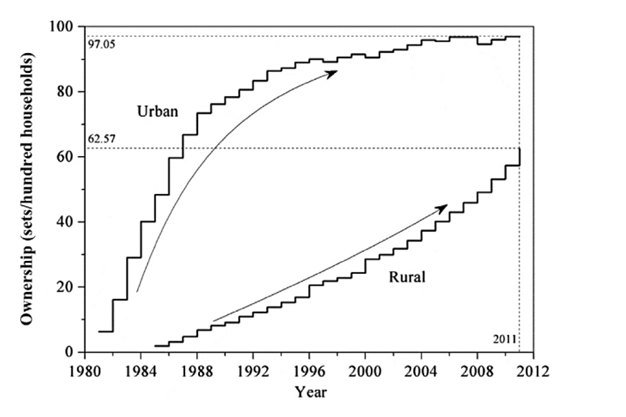

Much room for progress remains. In 2016, only 0.6 percent of Chinese households and 0.1 percent of Indian households had a dishwasher, compared to 67 percent of U.S. households, according to Euromonitor data. In 2016, microwave market penetration was just 23.4 of Chinese households and 3.1 percent of Indian households, compared to 91.3 percent of U.S. households. Only 15 percent of Indian households owned a refrigerator in 2006.

If prosperity continues to spread and poverty to decline globally, kitchen appliances and ready-made goods will free up more and more hours of women’s food preparation time around the world. There may always be freak accidents like the one in Manhattan, but there is no reason why innovation cannot lessen the risk by liberating women everywhere from kitchen chores.

This first appeared in the American Spectator.