Today marks the fourth installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org called Centers of Progress. Where does progress happen? The story of civilization is in many ways the story of the city. It is the city that has helped to create and define the modern world. This bi-weekly column will give a short overview of urban centers that were the sites of pivotal advances in culture, economics, politics, technology, etc. The third installment can be found here.

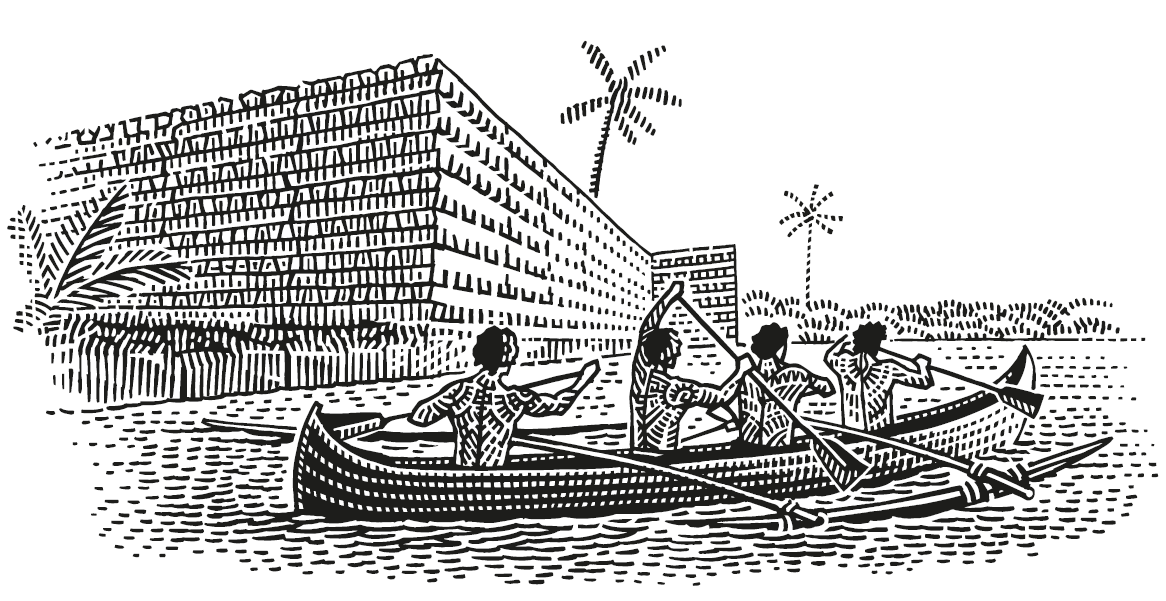

Our fourth Center of Progress is Nan Madol, a city that showcases the far reach of the first seafarers. Micronesia, where Nan Madol was eventually built, started to be settled by the ancient Austronesians over four thousand years ago. It was these people who are thought to be the first humans to invent sea vessels.

Their invention allowed them to explore and populate much of the Indo-Pacific region during the so-called Austronesian Expansion. The Expansion peaked between 3000 and 1000 BC—although the Austronesians did not reach some islands in Polynesia until after the year 1000 AD and may not have settled New Zealand until around 1300 AD.

The stone city of Nan Madol, constructed around 1100 AD (with parts perhaps dating to as early as the year 500 AD), toward the end of the Austronesian age of discovery, stands as a testament to the first seafarers’ ingenuity and the wide reach of their exploration.

Before the advent of seafaring vessels, people could not travel beyond coastlines. As such, many hospitable lands remained uninhabited by human beings because no one could reach them. Various cultures independently created dugout canoes to travel along rivers, but the oceans remained impassable. Eventually, people came to wonder what lay further away—across the oceans. The invention of seafaring boats allowed the ancient Austronesians to explore new lands and quite literally expanded humanity’s horizons.

The invention of seaworthy vessels was likely a gradual process of improving upon river boats until they could handle the rough waters of the open ocean. To people back then, the ocean must have seemed as daunting an obstacle as outer space seems to us, but they persevered. Some of the early attempts at voyaging were no doubt failures, resulting in many lives tragically lost at sea. But each time that the explorers successfully ventured out a bit farther from the shore and returned safely their confidence grew.

The first true ocean-going vessels were outrigger boats: watercraft featuring lateral support floats known as outriggers, which are secured to one or both sides of the boat’s main hull. The outriggers help to stabilize the boat and prevent it from capsizing on the choppy waters of the open sea. The first outriggers may have been simple logs or fallen tree branches, but their shape was refined over the years with careful craftsmanship to maximize stability. To steer their outrigger vessels, the first seafarers often used sails woven from salt-resistant pandanus leaves.

In due course, the seafarers developed catamarans, or watercraft featuring parallel hulls in place of mere outriggers. Some catamarans were large enough to carry more than 80 people, and could handle being out at sea for months on end.

Today, the ruined stone city of Nan Madol stands on elevated, artificial islets on the eastern edge of the island of Pohnpei, which is a little smaller in area than New York City. The island is now part of the Federated States of Micronesia. Nan Madol is a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site. Nan Madol means “in the space between things,” in reference to the canals crisscrossing between the islets. The stone city remains have been partially overgrown by mangroves and other plants, lending the ruins an eerie aura. The well-known horror fiction writer H.P. Lovecraft was inspired by the ruins and modeled the city where his famed fictional monster Cthulhu dwells after Nan Madol.

Scholars disagree on precisely where the Austronesian people originated, with theories ranging from Taiwan to various islands in southeast Asia. But whatever their point of origin, the Austronesians’ outrigger canoes and catamarans allowed them to spread out across the Pacific, exploring and settling new lands. Prior to the 16th century European Age of Discovery, Austronesians were the most widespread ethnolinguistic group, spanning half the planet. Remnants of Austronesian settlement can be found in places as disparate as New Zealand in Oceania, Easter Island in the southeastern Pacific Ocean near South America, and Madagascar in Africa.

Even as they spread out across half of the world over the course of centuries, the vastly dispersed Austronesian population maintained many things in common. They spoke variations of the same language, and shared many of the same technologies and traditions, such as body tattooing, jade-carving, megalithic construction, stilt houses, and various artistic motifs.

The Austronesians also partook in a common set of agricultural techniques and raised many of the same animals, such as chickens, pigs, and dogs, and grew many of the same plants. Those included bananas, coconuts, breadfruit, yams and taro. They transported seeds and animals on their boats during their sea migrations. After their settlements reached their furthest extent east, they introduced sweet potatoes from South America to the islands of the Pacific and to southeast Asia around 1000 AD–1100 AD.

Among the places that the Austronesians settled during their Expansion were the Micronesian islands located in the western Pacific Ocean. They were the first human beings to set foot there, as the remote islands were unreachable before the invention of seaworthy vessels. It is believed that the eastern Micronesian islands such as Pohnpei were first settled by seafarers venturing out from the islands now known as Vanuatu and Fiji, sometime before 1000 BC. Archaeological and linguistic evidence suggests that the settlers worked their way up the chain of islands gradually.

During the peak of the Austronesian Expansion, despite building a variety of impressive megalithic stone artworks—such as those in Lore Lindu National Park on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia, which date to 2000 BC—the Austronesian people mainly constructed their homes of materials that decompose. As a result, they left no well-preserved ruined cities from that era.

Sometime around the year 1100 AD, the seafarers found a reason to build a city out of a more lasting material: stone. The decentralized chieftain-based system of Micronesia had changed into a more unified economic and religious culture centered on Pohnpei and the island’s chief. That chief, who established the Saudeleur dynasty and a system of absolute rule, chose to build a royal and ceremonial city out of stone for the prestige that the material conferred. The ruins of Nan Madol have thereby survived through the centuries and offer us a window into the Austronesians’ lives. Evidence suggests that Nan Madol was the first capital city in the Pacific representing unity under a single chief.

The city’s walls are built of basalt cut into the shape of interlocking logs—perhaps a legacy of the wood-based building techniques that the culture practiced before shifting to stone as a building material. The walls enclose an area almost 5 thousand feet long and nearly 2 thousand feet wide. The total weight of the basalt columns or logs that had to be transported in order to construct the city is estimated at 750,000 metric tons.

That means that to build Nan Madol, the people of Pohnpei moved an average of 1,850 tons per year over four centuries. Given that the island had a population of less than 30,000 people, that was a great feat. The method that they used to move the stones remains a mystery. “Not bad for people who had no pulleys, no levers and no metal,” noted Rufino Mauricio—an archeologist who works at the Nan Madol site and who is affiliated with the Federated States of Micronesia Office of the National Archives, Culture, and Historic Preservation.

If you could visit Nan Madol in its prime, you would be struck by the way that boats acted as a vital part of the city. The city contains nearly 100 artificial man-made islets or platforms built of stone and coral, which are crisscrossed by tidal canals. Nan Madol’s canals served as the thoroughfares by which people traveled around the city, using wooden canoes. The city has thus been nicknamed the “Venice of the Pacific.” It is the only ancient city ever to be built atop a coral reef.

Raising your gaze beyond the canals, you would have seen an affluent city containing stone palaces, temples, mortuaries and residential homes for the society’s nobility. The city was constructed in part to serve as an enclave to house the chief and the nobility. You would thus have immediately noticed that the majority of the roughly one thousand residents were either high-status individuals, extensively adorned in jewelry such as necklaces and arm rings, or their servants. The walls surrounding the city acted as fortifications to protect the high-status inhabitants.

But Nan Madol was also home to a sprawling urban marketplace, in which you could purchase goods ranging from trochus shells and quartz crystals to distinctive pottery. You would have seen merchants hawking trolling lures for fishing, stone and shell tools, and carefully carved bead necklaces. Evidence suggests that the marketplace also may have sold pet dogs and turtles. Food stalls likely sold pork, poultry, fish, rice, copra, bananas, breadfruit and taro—among other foods.

No food was grown in Nan Madol itself. Instead, the city served as a center of trade for food and other goods transported by boat from elsewhere in the chiefdom. Nan Madol was also a major spiritual center and the site of many religious ceremonies, such as an annual ceremony of atonement in which priests would offer cooked turtle to saltwater eels. (Eels were considered to be sacred.) Additionally, Nan Madol was a place for diplomacy and important political gatherings.

After expanding their territory to cover half of the world, the Austronesians mysteriously ceased voyaging, instead settling down permanently in places such as Nan Madol. According to legend, Nan Madol was founded by twin brothers who came to Pohnpei by boat from an unknown island, seeking a place to build an altar so that they could worship the god of agriculture. That legend reflects the end of the age of voyaging and the transition to a stationary, agricultural way of life.

Today, Nan Madol is best known as the seat of power during the Saudeleur dynasty of chiefs, who ruled from around 1100 to around 1628. According to the oral histories passed down on Pohnpei, the dynasty became increasingly oppressive with each generation, as each new chief sought to replace the autonomous and decentralized Pohpeian culture with an ever-more abusive and centralized system of social control. The rule of the last chief was so cruel that it sparked mass discontent.

The oral histories relate that the dynasty ended when that tyrant chief was overthrown (with the full support of the local people) by Isokelekel—a semi-mythical hero and warrior. He was purported to be a demigod from the neighboring Micronesian island of Kosrae and came to power in the 16th or the 17th century AD. His successors abandoned Nan Madol in the early 19th century.

The invention of sea travel was a revolutionary breakthrough in the history of transportation. By showing the far reach of the first seafarers, Nan Madol has earned its place as our fourth Center of Progress. The same spirit of discovery that drove people to set sail on the ocean in search of new lands eventually guided our species to develop air travel and space travel, and may one day lead humanity to set foot on other planets.