You can read about other Centers of Progress in our book.

Today marks the twenty-third installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org called Centers of Progress. Where does progress happen? The story of civilization is in many ways the story of the city. It is the city that has helped to create and define the modern world. This bi-weekly column will give a short overview of urban centers that were the sites of pivotal advances in culture, economics, politics, technology, etc.

Our twenty-third Center of Progress is London during the late 18th and early 19th century, when the city played host to debates on the nature of human rights that would change the world. Today, we take the norm that no person can buy or sell another human being for granted, but it took humanity a long time to arrive at that norm. Slavery was accepted and rarely questioned for millennia throughout the world, but today slavery is illegal in all countries. Legal battles fought in London and legislative actions taken in London helped to end the global slave trade and bring about the dramatic change in attitudes about slavery—an invaluable victory for human freedom.

Today, London is a city that needs no introduction. It is well-known as one of the world’s foremost global cities as well as the capital and most populous city in the United Kingdom. London is recognized as a center of commerce, finance, the arts, education and research, and is among the globe’s most popular tourist destinations. It is home to Buckingham Palace, the iconic clock tower Big Ben, the British Museum, and Europe’s tallest Ferris wheel—the London Eye. It also houses four different UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Westminster Abbey, the medieval Tower of London, Kew Gardens, and Maritime Greenwich.

Evidence suggests that the site of present-day London has been inhabited since at least the Bronze Age. However, the site’s importance began when Romans founded a port settlement there in 43 AD. It was known as Londinium. Londinium soon became a regional trade hub, major road nexus, and the capital city of Roman Britain during most of the time that Romans ruled the province of Britannia. Once the Romans left Britain, Anglo-Saxons gained rule in London and the city became the capital of the eventual Kingdom of England. After the Norman conquest in 1066, William the Conqueror became the English king and it was during his rule that London was first linked to attempts to limit slavery.

In different parts of the world, slavery had long been subject to sporadic criticism, various limits and even brief bans. For example, Emperor Wang Mang banned slavery in China in 9 AD. It was reinstated soon afterward. In the 7th century, the Frankish Queen Balthild, herself a former slave, helped enact reforms that prevented the trade of Christian slaves. In the 740s, Pope Zachary banned the sale of Christian slaves to Muslims. And in 873, Pope John VIII similarly called the enslavement of Christians sinful and advocated for the slaves’ release.

But the early attempt to restrict slavery that would have the most lasting impact occurred in London. According to the Domesday Book, an extensive survey of England and parts of Wales completed in the 1080s, around 10 percent of people in the area were slaves. In 1080, William the Conqueror banned the sale of slaves to non-Christians. In 1102, the ecclesiastical Council of London banned the slave trade within England, decreeing “Let no one dare hereafter to engage in the infamous business … of selling men like animals.”

Within a generation, slavery had all but vanished in England. It was replaced by serfdom. Unlike slaves, serfs could at least own property. Also, they were not at risk of separation from their families. Alas, they could not move, since they were perpetually confined to the land they worked. A feudal lord could sell that land, thus changing whom the serf served, but serfs themselves were not sold.

Since time immemorial, every major civilization practiced some form of slavery for most of history. Slavery has existed since at least 3500 BC, when the ancient Sumerians practiced it. Improvements in seafaring led to globalization of the slave trade. The Atlantic slave trade, for example, lasted from the 16th to the 19th centuries, and involved the transport of millions of sub-Saharan Africans across the ocean to live in bondage.

While the first foreign slave-traders in sub-Saharan Africa were Arab—Saudi Arabia, in fact, did not outlaw slavery until 1962—Europeans were soon prominent participants in the maritime slave trade, transporting roughly 11 million slaves out of Africa. The first and the worst offender was Portugal, which transported around 5 million slaves from the African slave markets mainly to its colony of Brazil.

Britain transported the second-highest number of enslaved Africans (2.6 million) to its various colonies. At least 300,000 African slaves were shipped to Britain’s North American colonies that would later become the United States. However, the near-total absence of slavery within Britain itself, which had persisted since the reforms of William the Conqueror, would prove critical to turning British hearts and minds against the institution.

As is widely known, the African slaves were treated as chattel rather than as people, and the conditions of the slave ships were horrific, with many enslaved people not surviving the journey. Most of those who made it through the voyage then lived the nightmare of forced, grueling agricultural labor on New World plantations. Slaves on the Caribbean and Brazilian plantations endured the worst conditions and suffered the highest fatality rates.

An enslaved Barbadian teenager, Jonathan Strong, was brought to London by his slave-master, who in 1765 beat Strong with a pistol and left him for dead in the street. Strong, bleeding and left mostly blind by the attack, ended up at a medical clinic for the poor held in Mincing Lane. There, as he received treatment for his wounds, Strong made an impression on the physician’s visiting brother—Granville Sharp (1735–1813).

Sharp, who was born in Durham but had lived in London since the age of fifteen, was forever changed by the encounter. He and his brother took Strong to a hospital and paid for the latter’s months-long treatment there. But not long after becoming well enough to leave the hospital, Strong was recaptured by his former enslaver, who attempted to sell Strong to a Jamaican plantation.

Sharp successfully defended Strong’s freedom, defeating Strong’s former slave-master in court—but only on a technicality. Tragically, Strong’s health was permanently damaged from the pistol attack and he passed away at the age of 25 in 1770. Sharp devoted himself to bring about a definitive legal ruling on the question of whether a man could be compelled to leave Britain and enter slavery, and his efforts earned him a reputation as an Enlightenment thinker and anti-slavery campaigner. He was not alone. The abolition movement in Britain was growing.

In 1769, another slaver from the colonies attempted to bring an enslaved man, James Somerset, to London. In 1771, Somerset escaped. In less than two months, Somerset was captured and arrangements were made to sell him again into slavery in Jamaica. Three Londoners applied for Somerset to receive a hearing, and their petition was granted. Many concerned Britons sent money to launch a legal defense for Somerset, but several lawyers volunteered to do the case pro bono. Sharp advised Somerset’s lawyers extensively.

One barrister, William Davy, famously cited in Somerset’s defense an alleged 1569 case in which a cartwright attempted to bring a slave to England from Russia. In that case, it was resolved that England’s air was “too pure” for a slave to breathe and that anyone in England was therefore free. Or, as the London-born jurist Sir William Blackstone (1723–1780) had once put it, “The spirit of liberty is so deeply ingrained in our constitution that a slave, the moment he lands in England, is free.”

Somerset won his case. The ruling stated that, while in Britain, Somerset was free. Furthermore, he could not be forced to depart the country. The ruling was a turning point.

Regardless of William the Conqueror’s original motivations behind limiting slavery, by the time of the Somerset judgment, the absence of slavery in Britain had become a matter of British pride. It was also a moral issue among several Enlightenment thinkers, members of the clergy—including Anglican cleric John Newton (1725–1807), the writer of the well-loved hymn “Amazing Grace”—and the general public.

By 1807, thanks to mounting public pressure and the work of tireless reformers such as William Wilberforce (1759–1833) in Britain’s London-based parliament in Westminster, Britain banned the international slave trade with the Slave Trade Act. When diplomatic efforts to pressure Paris and Vienna to sign similar legislation proved futile, public support for the use of force rose.

Decision-makers in London ordered the British Navy to form the West Africa Squadron in 1808 to blockade West Africa and stop the movement of slave-transporting ships across the Atlantic Ocean. By the 1850s, the West Africa Squadron consisted of approximately 25 ships, two thousand British men and a thousand additional crew members who were recruited locally, mainly from what is now Liberia. The British naval officers were paid a reward for each slave that they freed, but the main incentive was humanitarian—by that point, anti-slavery efforts were hugely popular in Britain. As the poet Alfred Tennyson (1809–1892) put it, “This spirit of chivalry… we see it in acts of heroism by land and sea, in fights against the slave trade.”

Between 1808 and 1860, the West Africa Squadron successfully hunted down at least 1,600 slave ships and freed around 150,000 African slaves. Spain and Portugal attempted to continue the slave trade, often purchasing slaves from African sellers. In the mid-18th century, King Tegbesu of Dahomey in present-day Benin drew the equivalent of around 250,000 pounds annually—the greatest part of his income—selling slaves captured in battle to Europeans. His successor to the throne declared in 1840 in response to British pressures to stop selling slaves, “The slave trade is the ruling principle of my people. It is the source and the glory of their wealth… the mother lulls the child to sleep with notes of triumph over an enemy reduced to slavery.” His acceptance of slavery demonstrates how deeply the practice was still ingrained at the time, across the globe.

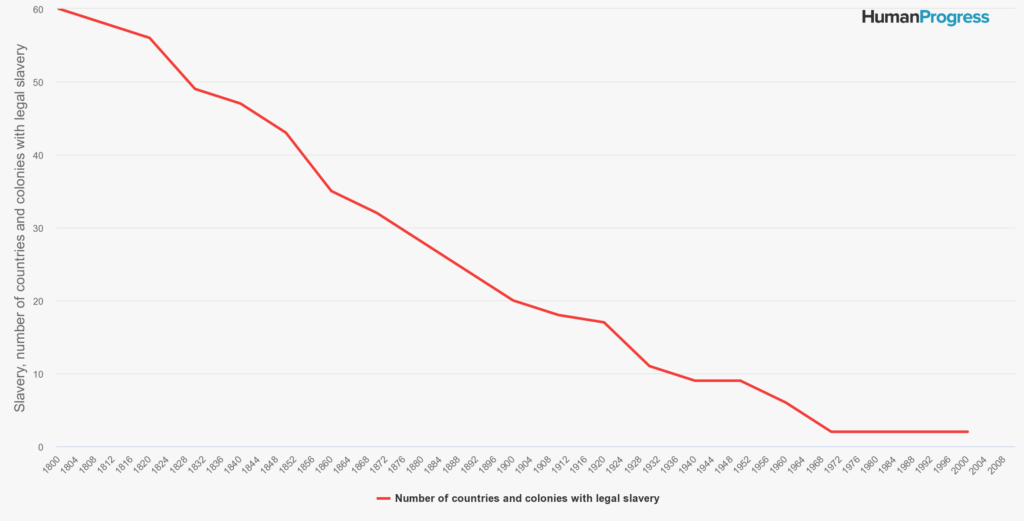

The British Navy eventually blockaded Brazil as well and succeeded in halting the Brazilian slave trade in 1852. But the effects of the abolition movement that started in London did not stop there. The movement saw a revival in the 1860s, when David Livingstone, the Scottish physician and prominent member of the London Missionary Society, published reports describing the Arab slave trade in Africa that too moved the British public. In the 1870s the British Navy again devoted resources to stopping the slave trade—this time by traders based in Zanzibar. Thanks in part to efforts launched in London, the number of countries with legal slavery plummeted throughout the 19th century.

While the lawmakers of London during the 18th and 19th centuries were far from perfect, their anti-slavery zeal helped to change the world for the better. As the Irish historian William Lecky (1838–1903) put it, “The unweary, unostentatious, and inglorious crusade of England against slavery may probably be regarded as among the three or four perfectly virtuous pages comprised in the history of nations.”

It was in London that British abolitionists organized, won court and legislative victories, launched naval ships with the mission of emancipating slaves, and ultimately helped to alter moral norms that had persisted since the dawn of civilization. For its critical role in ending the slave trade and de-normalizing the institution of slavery, London is justly our twenty-third Center of Progress.