Today marks the eleventh installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org called Centers of Progress. Where does progress happen? The story of civilization is in many ways the story of the city. It is the city that has helped to create and define the modern world. This bi-weekly column will give a short overview of urban centers that were the sites of pivotal advances in culture, economics, politics, technology, etc.

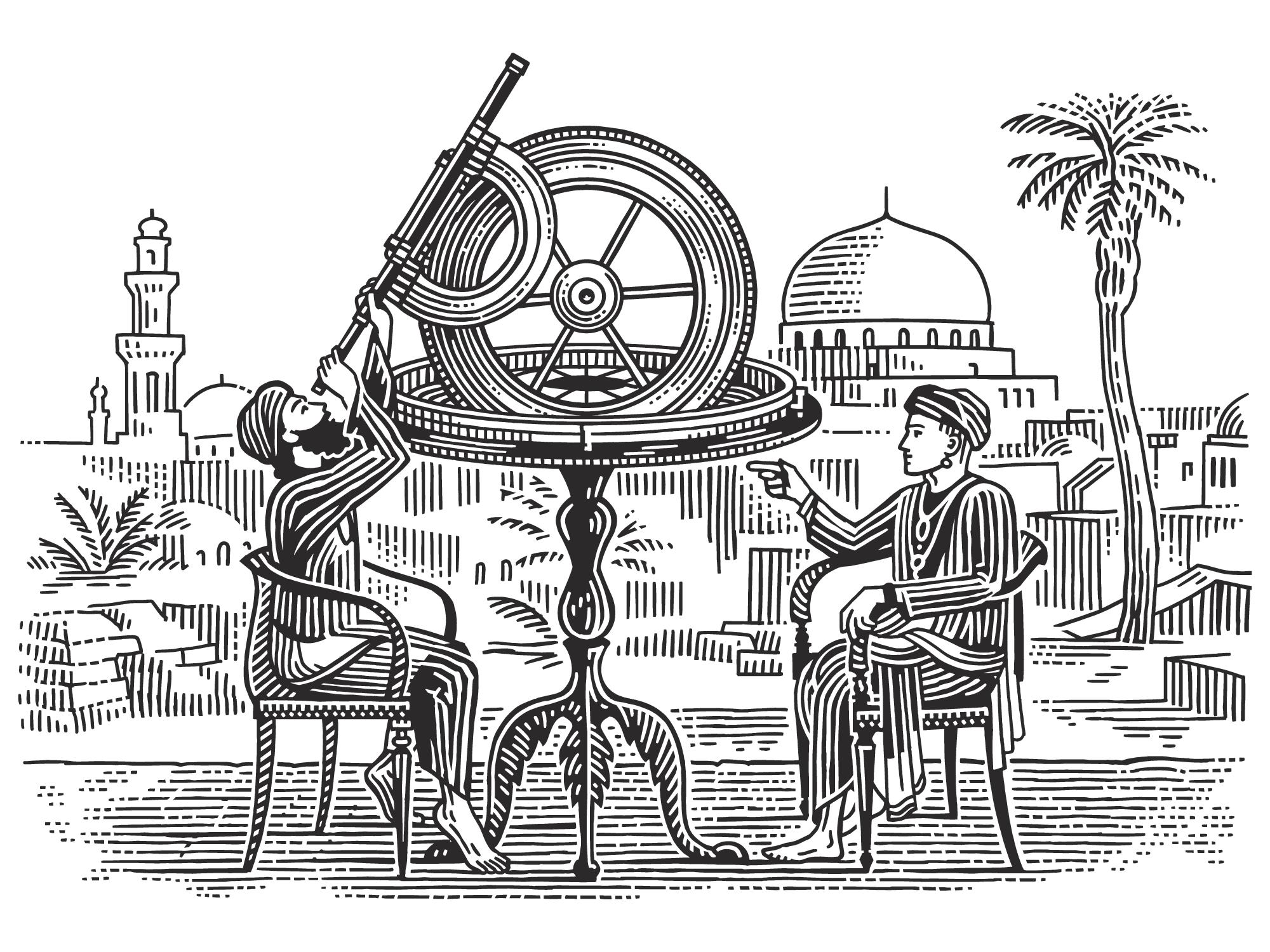

Our eleventh Center of Progress is 9th century Baghdad, during the Abbasid caliphate at the beginning of the so-called Islamic Golden Age. Baghdad was quickly growing into the world’s largest city and was a major learning center that saw breakthroughs in mathematics and, most notably, astronomy. As the intellectual capital of the Muslim world, which stretched from Spain to China, Baghdad attracted scholars from many different locations. While the predominant faith was Islam, the city became a melting pot of many other religions and cultures. For a time, Baghdad had a relatively open and tolerant society that allowed the city to flourish. The House of Wisdom was a library established in Abbasid-era Baghdad that soon grew into one of history’s greatest intellectual centers. It was a hub of translation, philosophical exchange, and innovation.

Today, Baghdad serves as Iraq’s capital, and some estimate it to be the Arab World’s third-largest city by population after Cairo and Riyadh. Tragically, the city has suffered many deaths, infrastructure damage, and a loss of irreplaceable historical artifacts due to recent conflicts and instability. It is among the most dangerous cities on Earth, and travel there is not recommended due to the risks of terrorism and armed conflict that plague the area. Today’s Baghdad is about as far as one can imagine from the city during its golden age when the urban center was a beacon of peace, tolerance, and scholarship. Literacy rates in the city may have been higher than those in many European cities at the time.

A small hamlet among several villages along the Tigris river first bore the pre-Islamic name Baghdad. The abundant water source has sustained human settlement in the area for millennia. In the 8th century, the Abbasid dynasty (the second Muslim dynasty) founded its capital in the propitious riverside location where the pre-existing settlement of Baghdad stood. While the meaning of “Baghdad,” is disputed, many scholars think that it means “Godgiven,” and is of Persian origin. During the Abbasid era, Baghdad’s official name was the “City of Peace,” or Madinat as-Salam.

The first Abbasid caliph, or ruler, Al-Mansur, summoned engineers, architects, surveyors, and artists from many countries to construct the city over four years (764–768 AD). The city’s construction began in July, as demanded by the Abbasid court astrologers. Those astrologers believed that starting construction under the Greek astrological sign of Leo, the lion, would ensure the city’s success.

While the city’s origin may have been dictated by astrology, a pseudoscience, there was not always a stark distinction between astrologers and astronomers. People who believed that the night sky could foretell human destinies were highly motivated to accurately predict the stars’ movements. Hence many astrologers studied legitimate astronomy, and many people considered astrology to be a branch of astronomy for centuries.

If you could visit Baghdad during its golden age, you would have entered a hectic commerce and scholarship center teeming with people of many different cultures speaking various languages. Many Baghdadis would have worn sandals and luxurious garments combining elements of the Arab, Irano-Turkic, and Hellenistic Mediterranean styles of dress. At the center of the city’s circular layout, defined by rounded archways and curving walls, rose the domes of the caliphal Palace of the Golden Gate and the city’s main mosque.

The 9th-century author Al-Jahiz wrote, “I have seen the great cities, including those noted for their durable construction. I have seen such cities in the districts of Syria, in Byzantine territory, and in other provinces, but I have never seen a city of greater height, more perfect circularity, more endowed with superior merits or possessing more spacious gates or more perfect defenses than [Baghdad].”

Baghdad was abuzz with commerce. Alongside the city’s four main roads, positioned like spokes on a wheel within the city’s circular design, stood vaulted arcades where merchants conducted their trade. In the crowded chaos of the city’s famous bazaars, you would have found goods from around the world, delivered by caravans of camels traveling the Great Khurasan Road to the city or arriving via the Tigris river trade route. You would have seen fine silk and pottery from China, elephants and spices from India, as well as rubies and other precious stones from Sri Lanka, and local delicacies such as judhaba. (Medieval Baghdadis were passionate about food, with the city’s leaders holding elite cooking competitions). Horrifyingly, you would also have seen people for sale—Baghdad practiced slavery, as did all major societies at that time.

In the bazaars, you would also find astrologers offering their services and many objects for sale decorated with artistic depictions of the planets and the Greek zodiac constellations. But there was more to the city’s connection to the night sky than a popular enthusiasm for astrology.

In the House of Wisdom or Grand Library of Baghdad, you would have seen astronomers hard at work, occupying a prominent position alongside other scholars. Adding to the city library’s collection of books and manuscripts became a point of pride for the city’s rulers. By the 9th century, the city housed an immense amalgamation of writings composed in Persian, Syriac, Sanskrit, Greek, and other languages, and produced Arabic translations of those works. Baghdad’s scholars’ large-scale translation effort has come to be known as the “Translation Movement,” sometimes called the Greco-Arabic translation movement due to its emphasis on translating Greek wisdom.

The Caliph Al-Ma’mun, who reigned from 813 AD to 833 AD, allegedly paid one particularly acclaimed translator, Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809–873 AD), the weight in gold of every book that he translated. He felt that wisdom was, quite literally, worth its weight in gold. Ishaq, nicknamed “Sheik of the translators” (sheik being a title for a prince or ruler), became the era’s most prolific decipherer of Greek medical and scientific texts. He was a Christian, and his ability to achieve a high social position despite being part of a religious minority group testifies to the cosmopolitanism and tolerance of the era. His son, Ishaq ibn Hunayn (circa 830–circa 910 AD), continued the family tradition by translating Euclid’s Elements and Ptolemy’s Almagest into Arabic. The city’s leaders had long admired Euclid, and Baghdad’s circular design may be an homage to Euclid’s geometric teachings.

The Almagest was the first major work on astronomy. After that tome’s translation into Arabic, Baghdad’s astronomers set about correcting several of Ptolemy’s calculations regarding the planets’ movements. They also perfected the astrolabe, an important tool not only in astronomy but in navigation. Furthermore, they developed spherical trigonometry and algebra, two forms of math essential to calculating the stars’ movements with precision.

Muhammad ibn Musa Al-Khwarizmi, a Persian polymath, astrologer, and astronomer appointed to head the House of Wisdom in 820 AD, invented the sine quadrant. That instrument takes angular measurements of altitude used in astronomy and navigation. In 828 AD, Caliph Al-Ma’mun ordered the building of the first astronomical observatory in the Islamic world, within the House of Wisdom. The historian and scientist Abul Hasan Al-Masudi, sometimes called the “Herodotus of the Arabs,” who was born near the close of the 9th century AD and worked in the 10th century AD, may have even invented a precursor to the telescope.

The city’s openness to knowledge from foreign lands and scholars of diverse backgrounds allowed Baghdad to build on others’ work and produce groundbreaking original scholarship. One House of Wisdom scholar, Abu Yusuf Ya’qub ibn Ishaq Al-Kindi (circa 800–873 AD), whose work spanned fields as varied as astronomy, chemistry, mathematics, medicine, metaphysics, and music, exemplified the open and tolerant worldview that allowed Baghdad to thrive. “We ought not to be ashamed of appreciating the truth and of acquiring it wherever it comes from,” Al-Kindi wrote, “even if it comes from races distant and nations different from us. For the seeker of truth, nothing takes precedence over the truth, and there is no disparagement of the truth, nor belittling either of him who speaks it or of him who conveys it.”

In that era, such broad-minded sentiments were a rarity in most places on Earth. However, they were common among the elites of Baghdad. Al-Kindi was appointed by Caliph Al-Ma’mun to serve as the tutor to the caliph’s brother and eventual successor, Caliph Al-Mu’tasim, who ruled from 833–842 AD. That caliph, in turn, appointed Al-Kindi as tutor to the former’s son.

The prevailing interpretation of Islam encouraged philosophy and scientific inquiry. Several often-quoted hadiths, or sayings attributed to the prophet Muhammad, instructed faithful Muslims to “seek knowledge.” Those included an exhortation to “seek knowledge from the cradle to the grave” and “seek knowledge, even unto China.” Those sayings were representative of the attitude held by many of Baghdad’s scholars, some of whom even felt that there was a religious imperative to seek out knowledge. Baghdad’s scholars also believed strongly in human reason and the existence of sources of wisdom independent of divine revelation.

Unfortunately, there were also more conservative religious forces that viewed anything foreign, including foreign philosophy and scientific wisdom, as a threat to Muslim society. The conservative faction also regarded the idea of elevating human reason to the status of a source of wisdom, instead of relying solely on religious teachings for knowledge, to be blasphemous. Eventually, the triumph of the anti-rationalist and xenophobic interpretation of Islam and the subsequent persecution of the liberal Muslim scholars helped bring the Islamic Golden Age to an end.

Baghdad’s ultimate downfall came in the form of conquest. It is said that the Tigris River “ran black with ink” after the Mongol invasion in 1258 AD, led by Hulagu Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan. The Mongols demolished the House of Wisdom and allegedly threw its books in the river. Sadly, thousands of books that Baghdad collected and produced have been lost or destroyed.

But for a time, while Europe’s scientific scene stagnated amid that continent’s so-called Dark Ages, Baghdad’s scholars made significant strides to further human understanding of the cosmos. Advances in astronomy during the later European renaissance built largely upon translations of Arabic works. To this day, the field of astronomy owes a great debt to the scholars of Abbasid-era Baghdad. Many stars maintain the Arabic names assigned to them during the Islamic Golden Age, like Altair and Betelgeuse. And today’s astronomers still use the Arabic words for common astronomical terms such as zenith, azimuth, and nadir.

Baghdad during the 9th century is perhaps best-known as the setting of many of the One Thousand and One Nights tales, widely known as the Arabian Nights, which were initially compiled during the Islamic Golden Age. That compendium of stories includes many well-known fables, like those of Aladdin the thief and Sinbad the sailor. The tales have created an image of Baghdad in the popular imagination as a place of wonder and adventure. But in reality, the city was also the site of serious scholarly work.

For greatly advancing the field of astronomy and contributing to scholarship in several other areas such as mathematics, early Abbasid dynasty-era Baghdad merits its place as our eleventh Center of Progress. Through openness to international intellectual exchange, as well as original research, the House of Wisdom and Baghdad’s wider academic community made leaps that were key to many later developments in the study of astronomy. At a time when Europe was immersed in a stupor known as the Dark Ages, Baghdad had its eyes on the stars.